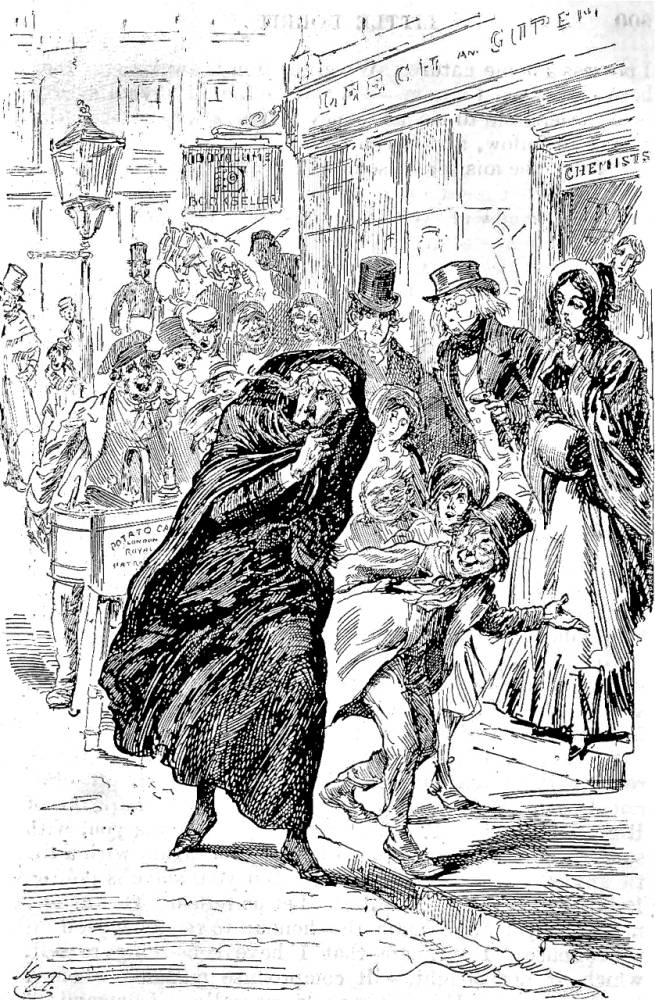

And she came towards him with her hands laid on his breast to keep him in his chair, and with her knees upon the floor at his feet, and with her lips raised up to kiss him, and with her tears dropping on him as the rain from heaven had dropped upon the flowers, Little Dorrit, a loving presence, called him by his name. — Book 2, chap. xxix, is the full title as given in the Harper and Brothers printing. The Chapman and Hall edition has an abbreviated version of this title: "With her hands laid upon his breast . . . . with her knees upon the floor at his feet . . . . Little Dorrit . . . . called him by his name" (See page 388.), Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's fifty-third composite woodblock illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.5 cm high by 13.6 cm wide, p. 377, framed, under the running head "The Easy and Agreeable Barnacle." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

He roused himself, and cried out. And then he saw, in the loving, pitying, sorrowing, dear face, as in a mirror, how changed he was; and she came towards him; and with her hands laid on his breast to keep him in his chair, and with her knees upon the floor at his feet, and with her lips raised up to kiss him, and with her tears dropping on him as the rain from Heaven had dropped upon the flowers, Little Dorrit, a living presence, called him by his name.

"O, my best friend! Dear Mr. Clennam, don't let me see you weep! Unless you weep with pleasure to see me. I hope you do. Your own poor child come back!"

So faithful, tender, and unspoiled by Fortune. In the sound of her voice, in the light of her eyes, in the touch of her hands, so Angelically comforting and true! — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 29, "A Plea in the Marshalsea," p. 388.

Commentary

Phiz in In the Old Room, the illustration for Chapter 28 (May 1857: Part Eighteen), had realised the dramatic visit by Blandois in which the devious Frenchman alludes to something he possesses that is of great value to Mrs. Clennam. In this original serial illustration, set in the rooms formerly assigned to William Dorrit, the illustrator and novelist point the reader towards the mysterious papers pertaining to Little Dorrit's Clennam inheritance, rather than to the romance of Amy Dorrit and Arthur Clennam — or Clennam's near-descent into madness in his Marshalsea cell. Over the course of the next week, Arthur becomes so depressed that he cannot sleep properly. At this point, on the sixth day when Clennam fully regains consciousness, Mahoney points the reader away from character comedy, melodrama, and sentimentality, the chief features of Hablot Knight Browne's original serial steel-engravings, towards romance and psychology. These sixties features are particularly evident in the scene in which Arthur Clennam, ascending from the depths of despair in the Marshalsea, first notices a bouquet of flowers on the table beside his chair, and then afterwards apprehends the presence of the Angel in the House, Amy Dorrit. Upon her return to London with Tip from Sicily just the previous evening, Amy had learned of Arthur's incarceration for debt from Mrs. Plornish, and has ministered to him in his delirium. Now she offers to effect his release through the application of her inherited fortune; however, not wishing to take advantage of her and ashamed of status as a debtor, he refuses.

Mahoney's illustration occurs fully eleven pages before the text realised, giving the artist the opportunity to depict the scene in a way that has a different effect from that of the text. Although this is Arthur Clennam's bedroom, no bed is visible, and, although the illustrator has included details from the text (the cup of tea and a large bouquet on the table beside him), Mahoney has emphasized the presence of a figure not immediately apparent at this point in the narrative, which describes the intimacy between the male and female protagonist as if nobody else were present. Suddenly, at the end of Clennam's being awakened by Amy, Dickens mentions a third figure, whom the reader has apprehended from the first in the picture eleven pages earlier:

Looking round, he saw Maggy in her big cap which had been long abandoned, with a basket on her arm as in the bygone days, chuckling rapturously. [388]

Thus, Mahoney reminds the reader that this tender scene is within sanctioned, middle-class limits as it is chaperoned.

Amy's ministering to the older, debilitated Arthur Clennam in his prison cell anticipates Lucie Manette's caring for her wasted father, the Bastille Prisoner, in the Defarges' garret after his release in Dickens's next novel, A Tale of Two Cities, emphasizing the societal role of even young women as domestic care-givers in such scenes as The Shoemaker (Book I, Chapter 6, June 1859). Dickens has handled the propriety of Amy's tending the thirty-year-old bachelor by inserting Maggy into the romantic scene.

Relevant Illustrations, 1857 through 1910

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's title-page vignette depicting Arthur's breaking the news of the inheritance to the Patriarch of the Marshalsea and his daughter, Joyful Tidings — Book I, Ch. XXXV (1863). Right: Harry Furniss's illustration of the witch-like Mrs. Clennam, getting lost as she tries to find the Marshalsea, Mrs. Clennam seeks Little Dorrit (1910). [Click the on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original study of the Arthur Clennam's becoming an inmate of the Marshalsea and receiving visitors, In the Old Room (Part 18: May 1857, II: 24). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Ch. 12, "Work, Work, Work." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 128-160.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 17 June 2016