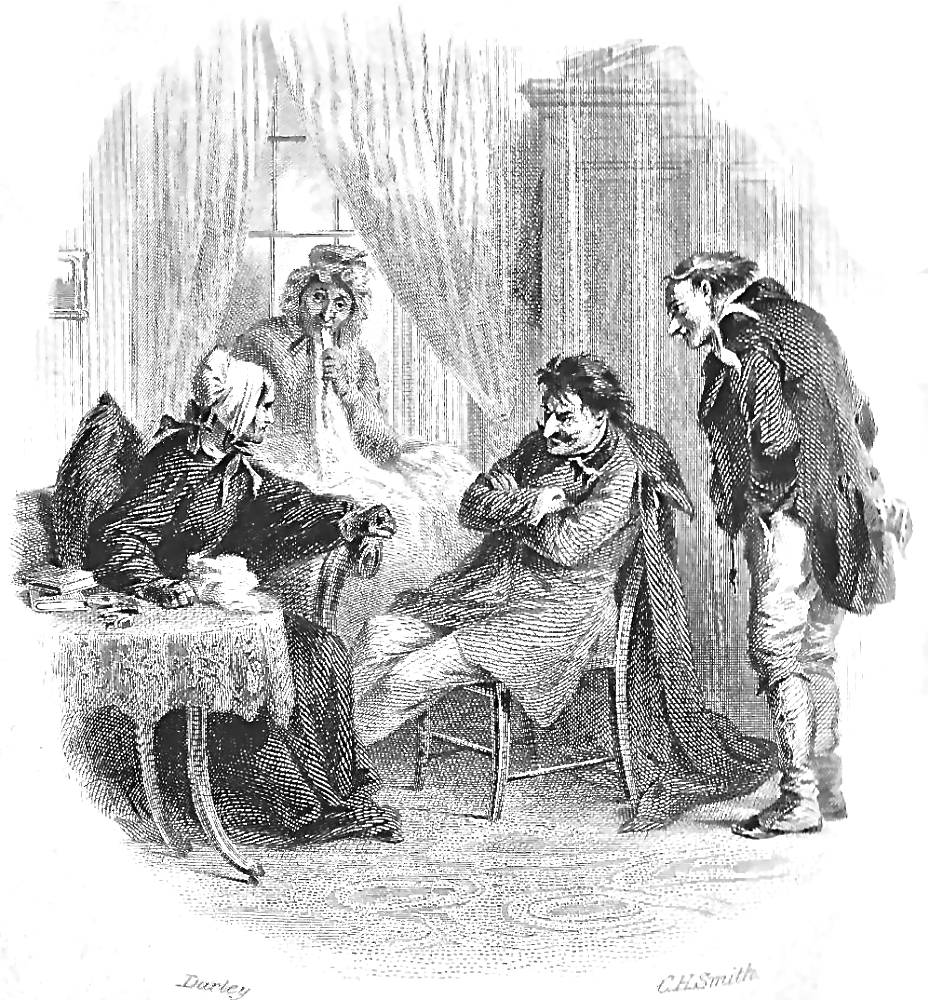

Mr. Flintwinch took a chair opposite to him, with the table between them. (See page 186), — Book I, chap. 30, Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's twenty-fourth illustration in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition volume of Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.5 cm high by 13.6 cm on p. 177 under the running head "A Stranger." The Chapman and Hall woodcut is identical to that in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition; however, the American volume has a much longer caption: On their arrival at Mr. Blandois's room, a bottle of port wine was ordered by that gallant gentleman; who coiled himself up on the window-seat, while Mr. Flintwinch took a chair opposite to him, with the table between them. — Book I, chap. xxx. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"I have a strong presentiment that we shall become intimately acquainted. — You have no feeling of that sort yet?"

"Not yet," said Mr. Flintwinch.

Mr. Blandois, taking him by both shoulders again, rolled him about a little in his former merry way, then drew his arm through his own, and invited him to come off and drink a bottle of wine like a dear deep old dog as he was.

Without a moment's indecision, Mr. Flintwinch accepted the invitation, and they went out to the quarters where the traveller was lodged, through a heavy rain which had rattled on the windows, roofs, and pavements, ever since nightfall. The thunder and lightning had long ago passed over, but the rain was furious. On their arrival at Mr. Blandois' room, a bottle of port wine was ordered by that gallant gentleman; who (crushing every pretty thing he could collect, in the soft disposition of his dainty figure) coiled himself upon the window-seat, while Mr. Flintwinch took a chair opposite to him, with the table between them. Mr. Blandois proposed having the largest glasses in the house, to which Mr. Flintwinch assented. The bumpers filled, Mr. Blandois, with a roystering gaiety, clinked the top of his glass against the bottom of Mr. Flintwinch's, and the bottom of his glass against the top of Mr Flintwinch's, and drank to the intimate acquaintance he foresaw. Mr. Flintwinch gravely pledged him, and drank all the wine he could get, and said nothing. As often as Mr. Blandois clinked glasses (which was at every replenishment), Mr. Flintwinch stolidly did his part of the clinking, and would have stolidly done his companion's part of the wine as well as his own: being, except in the article of palate, a mere cask.

In short, Mr. Blandois found that to pour port wine into the reticent Flintwinch was, not to open him but to shut him up. Moreover, he had the appearance of a perfect ability to go on all night; or, if occasion were, all next day and all next night; whereas Mr Blandois soon grew indistinctly conscious of swaggering too fiercely and boastfully. He therefore terminated the entertainment at the end of the third bottle.

"You will draw upon us to-morrow, sir," said Mr. Flintwinch, with a business-like face at parting.

"My Cabbage," returned the other, taking him by the collar with both hands, "I'll draw upon you; have no fear. Adieu, my Flintwinch. Receive at parting;" here he gave him a southern embrace, and kissed him soundly on both cheeks; "the word of a gentleman! By a thousand Thunders, you shall see me again!"

He did not present himself next day, though the letter of advice came duly to hand. Inquiring after him at night, Mr. Flintwinch found, with surprise, that he had paid his bill and gone back to the Continent by way of Calais. Nevertheless, Jeremiah scraped out of his cogitating face a lively conviction that Mr. Blandois would keep his word on this occasion, and would be seen again. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 31, "The Word of a Gentleman," p. 186-187.

Commentary

Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam's confidential clerk, is naturally suspicious of the flamboyant Frenchman with financial papers drawn on his mistress's house, and wants to gather further information about him. Having had a personal interview with the wily Mrs. Clennam, who has essentially turned his case over to her subordinate, Blandois (Rigaud's pseudonym for himself as his reputation had already preceded him to Challons when he arrived at that city in north-western France) has tea with the arch invalid, and then adjourns to his hotel-room to drink wine with Flintwinch, perhaps hoping to elicit more information about the secretive and obviously wealthy reclusive Mrs. Clennam. In spite of their drinking, Flintwinch yields no such information. Mahoney's handling of the scene is a study in contrasts with the dark, middle-aged, bearded Frenchman in evening dress but a casual posture seated opposite the older, balding English clerk in somewhat old-fashioned dress (including gaiters), a businessman straight-laced and taciturn in contrast to his voluble Gallic companion, smoking a small cigarette (as is usual in illustrations of him).

The Consumption of Port in Dickens's Works

Curiously, the "wine" that Blandois orders is not a French vin ordinaire, but a fortified wine — port, an imported after-dinner alcoholic beverage from Portugal (Vinho do Porto) consumed by a number of other Dickens characters, including Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney, drinking the medicinal port in Oliver Twist, Mr. Bintrey and Mr. Walter Wilding drinking vintage port in No Thoroughfare, and The Sergeant and Uncle Pumblechook in Great Expectations. As these citations demonstrate, the imbibing of port tended to be a masculine taste, and often associated with some special occasion or toast, port being an expensive alcoholic beverage beyond the means of the working class. The imbibing of port is most common, along with the consumption of other sorts of alcoholic beverages, in Pickwick, with greatest toper of all, the dissenting minister Mr. Stiggins ("the red-nosed man") being addicted to mulled port, made with cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, mace and sugar to taste. According to The Charles Dickens Cookbook, "The final heating was usually achieved with the aid of a special 'sugar-loaf hat' described in the making of Purl" (159), a specialty of The Six Jolly Fellowship-Porters in Our Mutual Friend, a less sophisticated mulled beverage made with spiced ale, nutmeg, ginger, sugar, and gin. Such plebeian alcoholic constituents suggest that Purl was a less costly and less sophisticated a beverage than mulled Port. Dick Swiveller in The Old Curiosity Shop is inordinately fond of purl, as Darley shows in "Marchioness, your health. You will excuse my wearing my hat. . . " (1861).

After the Treaty of Metheun in 1702, reduced tariffs on Portuguese wines gave preferential treatment to the Portuguese import in the British wine market over French wines, so that the popularity of port ("blackstrap" as it was popularly called because of its dark color and astringency), accelerated in early eighteenth century Britain, with the excise on a bottle of Port being a third less than that of a bottle of French wine. By 1717, Portuguese wines in general accounted for more than 66% of all wine imported into Great Britain, whereas French wines accounted for a mere 4%. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French even attempted to disrupt the trade by invading northern Portugal between 1807 and 1809, damaging the economy of the principal wine-growing region, Douro. After the British wine merchants of Porto fled, the trade with Great Britain was severely impaired. Although the population rebounded in Great Britain after the Congress of Vienna which ended the Anglo-French conflict, port sales in England did not rebound, leveling off to the totals of the previous century. The British had simply diversified their tastes, which included the other fortified wine, sherry, from Spain, and brandy and water — a favourite of Tony Weller, the stout coachman of The Pickwick Papers, a beverage that he, his fellows, his son Sam and the attorney Mr. Pell quaff in Hablot Knight Browne's Mr. Weller and his friends drinking to Mr. Pell (November 1837).In 1859, whereas Great Britain imported 22,546 gallons of sherry from Spain, it brought in just 2,227 gallons on wine from France, but 4,171 gallons of port from Portugal, attesting to port's continuing popularity at the time that Dickens was writing Little Dorrit.

Although in this passage from Little Dorrit Blandois orders a single bottle of port, and the pair consume two further bottles, in the Mahoney illustrationthe pair are in the process of consuming the second bottle of the fortified wine, apparently without much effect on Mr. Flintwinch, who seems bent on patiently bent on drinking the Frenchman under the table when Blandois calls a halt with the end of the third bottle. In the illustration, the expansive Blandois already seems to be succumbing, although he is hardly an inebriate of the rank of Bob Sawyer, the alcoholic medical student and pharmacist of Dickens's first novel so often shown with either a glass or bottle in his hand, as in Conviviality at Bob Sawyer's (May 1837) and Mr. Bob Sawyer's Mode of Travelling (October 1837). Ironically, Dickens himself was relatively abstemious.

Blandois and Flintwinch from Other Early Editions, 1857-1910

Left:Felix Octavius Carr Darley's frontispiece showing Mrs. Clennam and Affery with Blandois and Flintwinch, Closing in — Book II, Ch. XXX. Centre: Phiz's illustration of the irascible Flintwinch berating his wife, Mr. Flintwinch has a mild Attack of Irritability for the same chapter (August 1856). Right: Harry Furniss's portrait of the daring Frenchman and terrified Affery Flintwinch, Rigaud enters Mrs. Clennam's house (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Marshall, Brenda. The Charles Dickens Cookbook. Toronto: Personal Library, 1981.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 5 June 2016