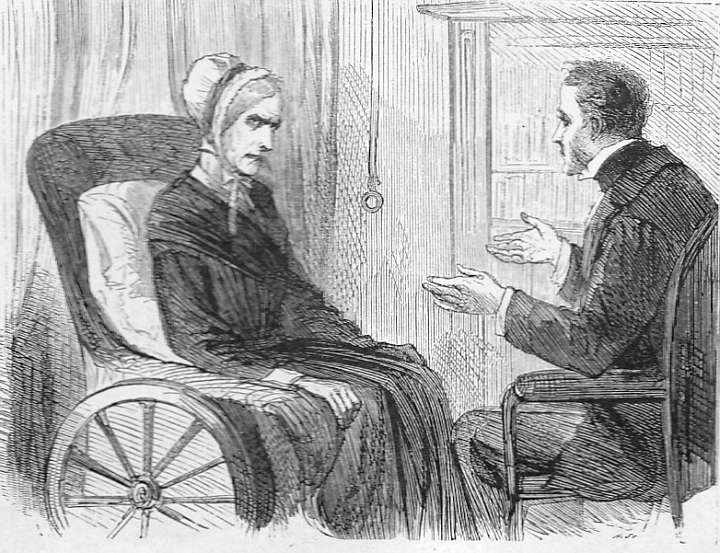

This refection of oysters was not presided over by Affery, but by the girl who had appeared why the bell was rung. (See page 27.) — Book I, chap. 5, "Family Affairs." Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's seventh illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. The wood-engraving by the Dalziels occurs on p. 25 in the Chapman & Hall volume, with the running head Mrs. Clennam's Oysters. 9.5 cm high x 13.6 cm wide, framed.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

But Mrs. Clennam, resolved to treat herself with the greater rigour for having been supposed to be unacquainted with reparation, refused to eat her oysters when they were brought. They looked tempting; eight in number, circularly set out on a white plate on a tray covered with a white napkin, flanked by a slice of buttered French roll, and a little compact glass of cool wine and water; but she resisted all persuasions, and sent them down again — placing the act to her credit, no doubt, in her Eternal Day-Book.

This refection of oysters was not presided over by Affery, but by the girl who had appeared when the bell was rung; the same who had been in the dimly-lighted room last night. Now that he had an opportunity of observing her, Arthur found that her diminutive figure, small features, and slight spare dress, gave her the appearance of being much younger than she was. A woman, probably of not less than two-and-twenty, she might have been passed in the street for little more than half that age. Not that her face was very youthful, for in truth there was more consideration and care in it than naturally belonged to her utmost years; but she was so little and light, so noiseless and shy, and appeared so conscious of being out of place among the three hard elders, that she had all the manner and much of the appearance of a subdued child. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 5, "Family Affairs," p. 27.

Commentary

The accompanying caption is somewhat different in the Harper & Bros. edition: They looked tempting; eight in number, circularly set out on a white plate, on a tray covered with a white napkin, flanked by a slice of buttered french roll and a little compact glass of cool wine and water — Book 1, chap. v. The Mahoney illustration parallels the 1856 Phiz steel-engraving of the uncomfortable interview between mother and son earlier, Mr. Flintwinch mediates as a friend of the family Arthur Clennam (January 1856: Part 2).

In the room lit by the fitful mid-morning sun of London, the three figures are the supposed invalid, the widow Mrs. Clennam, in her wheelchair, her thirty-something-year-old son Arthur (lately returned from the family business in China, probably Hong Kong) by the window, and Little Dorrit with the serving tray (centre). Arthur Clennam, studying both women by the ray of sunlight that penetrates this bedroom in the upper storey of the decaying mansion, finds Amy Dorrit, the occasional servant, an interesting subject for speculation. The passage realised introduces Amy Dorrit and establishes the connection between her and the Clennam household, where she has regular employment as a day-maid:

Little Dorrit let herself out to do needlework. At so much a day — or at so little — from eight to eight, Little Dorrit was to be hired. Punctual to the moment, Little Dorrit appeared; punctual to the moment, Little Dorrit vanished. What became of Little Dorrit between the two eights was a mystery. [27]

This speculation will lead Clennam to discover Amy's principal role as her father's companion in the infamous debtors' prison, the Marshalsea, located in the Borough (south of the Thames). As opposed to Phiz's original illustration for the fifth chapter, The Room with the Portrait (second monthly number, January 1856), Mahoney's description of the characters is intended to support the development of characterization and plot rather than to establish the gloomy atmosphere of the Clennam household.

In his characterization for the "Dickens on Tour" volume of the novel (Diamond Edition, 1867), American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Junior, epicts a sinister, cold, brooding mother and an earnest son, trying to explain himself — clearly, the scene illustrated in Mrs. Clennam and Arthur Clennam is from Book One, Chapter 5, but is typical of this awkward familial relationship throughout the novel. Both Harold Copping and Felix Octavius Carr Darley selected a much more positive scene for their depictions of Arthur Clennam as the saviour of the Dorrit Clan: Joyful Tidings — Book I, Ch. XXXV (1863), and Arthur Clenham Tells the Good News (1924). The emphasis in the Mahoney illustration, however, as in the Eytinge illustration, is the contrast between the open, generous, and thoughtful Arthur and his bitter, brooding, judgmental Calvinist mother. Mahoney is particularly interested — and intends that the reader be interested — in her peculiar self-denial in her interview with her son. At 11:00 A. M. punctually she takes a fortifying repast of oysters, but this morning, after arguing with her son and having her confidential servant, Jeremiah Flintwinch mediate, she wilfully denies herself this little treat. Thus, author and illustrator present the attentive reader with what seems like a small mystery which may be nothing more than a quirk of character. However, in reality her inexplicable self-denial of a small pleasure (one of the few open to an older woman wheel-chair bound at that time) and departure from daily routine is evidence of a deep-seated guilt which the presence of both Little Dorrit and Arthur exacerbates, for she is suppressing information vital to the interests of both: Amy Dorrit should be inheriting a considerable sum under the terms of the will of Arthur's uncle, and Arthur is not Mrs. Clennam's biological offspring. More important, perhaps, than these complicated plot gambits is the effect that harbouring such secrets is having on the dour, self-righteous, puritanical widow.

Arthur Clennam, Mrs. Clennam, and Amy Dorrit from Other Early Editions

Left: An early American visual interpretation of Arthur Clennam and Little Dorrit, Darley's Joyful Tidings. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the mother and son, Mrs. Clennam and Arthur Clennam. Right: The Harrold Copping illustration of Little Dorrit's receiving news of the inheritance, Arthur Clenham Tells the Good News. (1924) [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original January 1857 engraving of the listless Arthur Clennam, inspecting his late father's study, The Room with the Portrait. (January 1856) [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Harvey, John. Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini. Character Sketches from Dickens. Illustrated by Harrold Copping. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 2 May 2016