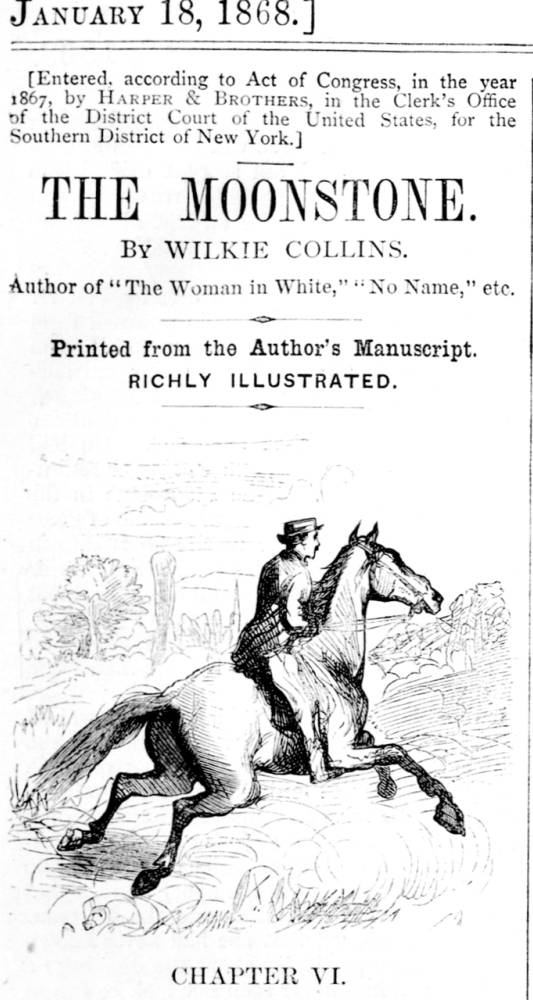

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder." Chapter 6 — initial illustration for the third instalment in Harper's Weekly (18 January 1868), p. 37. Wood-engraving, 6 x 5.8 cm. [The third headnote vignette prepares the alert reader for the significant role that the intelligent, sympathetic but somewhat feckless Franklin Blake, Rachel Verinder's cousin, will play in both the plot and the narration of the novel. Franklin Blake's riding to Frizinghall in Chapter 6 demonstrates his readiness to act rather than merely ponder or intellectualise when Rachel's interest is at stake. Taking Betteredge's advice, he decides to deposit Colonel Herncaste's birthday present for his niece in the local bank until the actual date upon which she will celebrate her eighteenth birthday.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Illustrations courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage Introduced by the Headnote Vignette for the Third Instalment

"I don't want to alarm my aunt without reason," he said. "And I don't want to leave her without what may be a needful warning. If you were in my place, Betteredge, tell me, in one word, what would you do?"

In one word, I told him: "Wait."

"With all my heart," says Mr. Franklin. "How long?"

I proceeded to explain myself.

"As I understand it, sir," I said, "somebody is bound to put this plaguy Diamond into Miss Rachel's hands on her birthday — and you may as well do it as another. Very good. This is the twenty-fifth of May, and the birthday is on the twenty-first of June. We have got close on four weeks before us. Let's wait and see what happens in that time; and let's warn my lady, or not, as the circumstances direct us."

"Perfect, Betteredge, as far as it goes!" says Mr. Franklin. "But between this and the birthday, what's to be done with the Diamond?"

"What your father did with it, to be sure, sir!" I answered. "Your father put it in the safe keeping of a bank in London. You put in the safe keeping of the bank at Frizinghall." (Frizinghall was our nearest town, and the Bank of England wasn't safer than the bank there.) "If I were you, sir," I added, "I would ride straight away with it to Frizinghall before the ladies come back."

The prospect of doing something — and, what is more, of doing that something on a horse — brought Mr. Franklin up like lightning from the flat of his back. He sprang to his feet, and pulled me up, without ceremony, on to mine. "Betteredge, you are worth your weight in gold," he said. "Come along, and saddle the best horse in the stables directly."

Here (God bless it!) was the original English foundation of him showing through all the foreign varnish at last! Here was the Master Franklin I remembered, coming out again in the good old way at the prospect of a ride, and reminding me of the good old times! Saddle a horse for him? I would have saddled a dozen horses, if he could only have ridden them all!

We went back to the house in a hurry; we had the fleetest horse in the stables saddled in a hurry; and Mr. Franklin rattled off in a hurry, to lodge the cursed Diamond once more in the strong-room of a bank. When I heard the last of his horse's hoofs on the drive, and when I turned about in the yard and found I was alone again, I felt half inclined to ask myself if I hadn't woke up from a dream. — "The Loss of the Diamond," Chapter 6, p. 38.

Commentary

At Betteredge's suggestion, Franklin Blake decides to delay handling the issue of the bequest of the Moonstone to Rachel Verinder by letting an institution once again take custody of the valuable. Not merely a nuisance or an unpleasant or inconvenient obligation, the Moonstone is "plaguy" in a sense that Franklin Blake may not realise in that it brings with it a curse that threatens his own future happiness as well as Rachel's, and results in the deaths of Rosanna Spearman and Godfrey Ablewhite. Was this masterstroke of delay really Betteredge's idea? The narrator would have us believe so.

This is our first glimpse of Franklin Blake. Introduced as riding a thoroughbred stallion, he is decidely of the "gentlemanly" class, just below the level of the aristocracy and at the very apex of the English middle class. Despite his jovial, optimistic outlook and his being the focal point of so much of the novel's action, Franklin is more than a mere male ingéue out of Sir Walter Scott or Charles Dickens; like Collins's heroine, Rachel Verinder, Collins's hero is complicated — and quirky. Owing to his having been educated in both France, Italy, and Germany, he exhibits habits of mind associated with these European nations, although the basis of his character is Anglo-Saxon practicality and common sense. Whereas Rachel is man-like in her tenacity and wilfulness (characteristics she shares with her uncle, Colonel Herncastle), Franklin vacillates and is unpredictable, which Collins's would have probably regarded as feminine traits. According to the conventional semiotics of crime-and-detection fiction, Franklin Blake should be the chief detective rather than a subordinate investigator and the editor to whom other narrators submit their accounts — and he should certainly not be the malefactor. However, whereas Rachel relies heavily on her physical senses and less on her intuition in believing that Franklin is the culprit, Franklin consistently reveals an open-mindedness that is rare in this novel. Although in the first rectangular full-size wood-engraving (no. 8) Franklin Blake seems an indolent and even listless young bourgeois, the illustrator (William Jewett) conveys his more active and decisive nature through the headnote vignette.

The three January 18th illustrations, taken together, underscore the importance of the terms of the will, and also indicate in the headnote vignette that Franklin Blake (seen riding a horse, presumably to Frizinghall) will transfer the gem to a bank rather than retain on his person or in his room. Whereas the first instalment introduced only Herncastle and the Brahmin guardians of the Moonstone, the second instalment (January 11) introduced the Verinders' trusted family retainer, Gabriel Betteredge (seen in both the headnote vignette and one of the two regular illustrations); Colonel Herncastle, no longer young or in uniform, appears with the butler; and by herself on the seashore the reader encounters the enigmatic figure of the reformed criminal Rosanna Spearman. The third instalment (18 January 1868) introduces the story's male protagonist, Franklin Blake, both in the headnote vignette as a solitary rider and in the first of the two main illustrations, with Gabriel Betteredge.

Despite his nineteenth-century hat and clothing, the youth on horseback in the Harper's illustration is the chevalier out of romance. A "bright-eyed young gentleman" with a "varnish from foreign parts," he becomes the subject of Rosanna's infatuation. He seems "like a prince in a fairy-story" to the orphaned, ex-convict and hunchback. Like the Brahmins, she risks all for the object of her devotion, hiding the paint-smeared nightgown to protect him, misguided as her effort may be in that it prevents the identification of the real culprit. The image of Blake on horseback here also presents him as a traveller, foreshadowing his wanderings in the East — although at this point is unlikely that either of the American illustrators would have known about this future plot development.

Related Materials

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone

- The 1944 Illustrations by William Sharp for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone (1946)

Last updated 22 November 2016