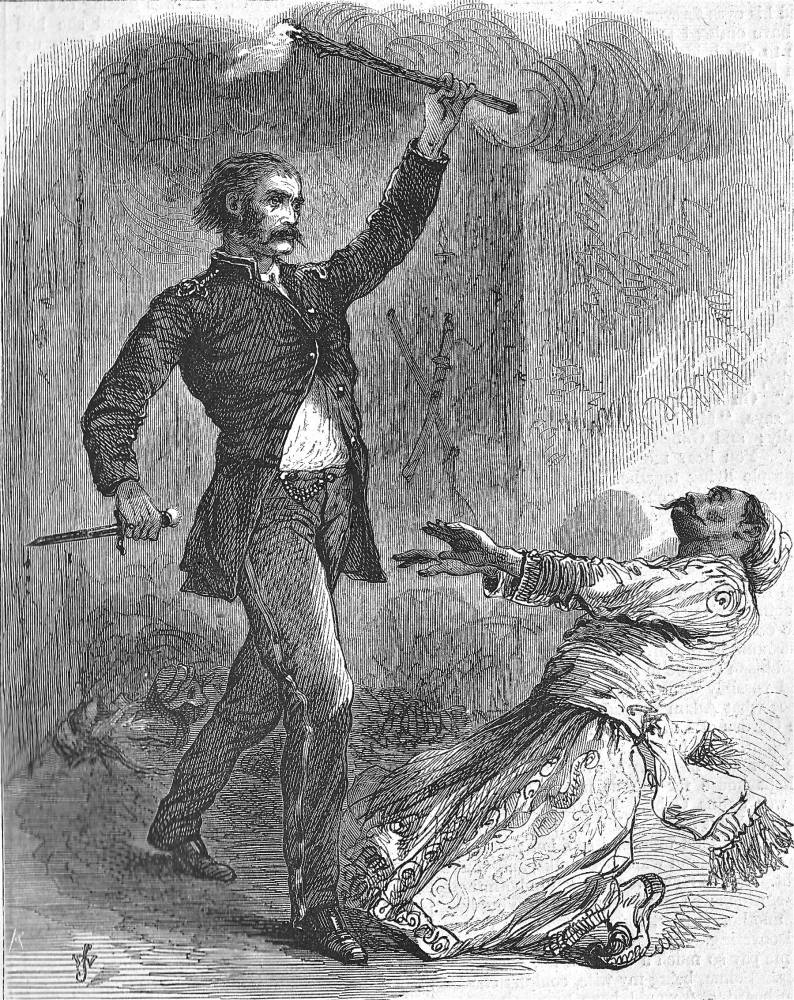

"The Moonstone will have its vengeance yet on you and yours!"

Harper & Bros. house illustrators

Wood engraving

14.5 cm high by 11.4 cm wide (5 ⅝ by 4 ⅝ inches)

First regular illustration for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance in Harper's Weekly (4 January 1868), page 5. Colonel Herncastle, having slain two of the guardians of the scared jewel, is about to slay the third brahmin. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Illustrations courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, UBC.

Passage Realised

While I was still vainly trying to establish order, I heard a frightful yelling on the other side of the courtyard, and at once ran towards the cries, in dread of finding some new outbreak of the pillage in that direction.

I got to an open door, and saw the bodies of two Indians (by theirdress, as I guessed, officers of the palace) lying across the entrance,dead.

A cry inside hurried me into a room, which appeared to serve as an armoury. A third Indian, mortally wounded, was sinking at the feet of aman whose back was towards me. The man turned at the instant when I camein, and I saw John Herncastle, with a torch in one hand, and a daggerdripping with blood in the other. A stone, set like a pommel, in the endof the dagger's handle, flashed in the torchlight, as he turned on me,like a gleam of fire. The dying Indian sank to his knees, pointed to the dagger in Herncastle's hand, and said, in his native language—"The Moonstone will have its vengeance yet on you and yours!" He spoke those words, and fell dead on the floor.

Before I could stir in the matter, the men who had followed me across the courtyard crowded in. My cousin rushed to meet them, like a madman. "Clear the room!" he shouted to me, "and set a guard on the door!" Themen fell back as he threw himself on them with his torch and his dagger.

I put two sentinels of my own company, on whom I could rely, to keep the door. Through the remainder of the night, I saw no more of my cousin. — "Prologue, The Storming of Seringapatam (1799)," 5.

Commentary for Three Illustrations in the First Serial Instalment: 4 January 1868

The first three illustrations together create a sweeping visual mini-narrative of the diamond's trajectory from the Indian shrine at Benares to the siege of Seringapatam to the Indians' quest to recover their stolen religious object in Britain. The linked images span from the eleventh century to the Victorian present and from ancient India to modern England, anticipating the enormous time scale as well as the cultural and geographical scope of Collins's narrative. — Leighton and Surridge, 211.

Since these three illustrations may be taken taken as an interconnected trio, the first of the three summarizes the sweeping action of the 4 Januay 1868 instalment, introducing the diamond's sacred nature, bringing on stage the European thief and murderer whose actions are apparently state-sanctioned, and concluding in the recent past (twenty years before the story's publication) with the descendants of the priests in the two previous frames who, as the present-day "guardians" of the gem, must locate and recover it, perhaps aided by supra-rational means (the clairvoyant). For the relationship between the initial vignette and the other two illustrations on page 5, see https://archive.org/stream/harpersweeklyv12bonn#page/4/mode/2up.

In addition, the first page of the Harper's serial introduces more visual perspectives than the letterpress, further complicating the points of view from which we see the cultural expropriation of the diamond. Part 1's letterpress begins with John Herncastle's cousin narrating the siege of Seringapatam (1799) and then shifts to the perspective of Gabriel Betteredge on recent domestic British events (1848). However, the Harper's illustrators provide two additional points of view. First, the image of the Benares shrine lies outside the text's predominantly British perspective, giving us a view that Herncastle's cousin refers to as existing only in "stories" and "traditions" and that situates the American reader at the foot of the Indian shrine at a time before the British presence on the continent. Moving to the right of the page, we get a radically proleptic view of Franklin Blake's glimpse (narrated to Betteredge in Part 3) of the Indians mesmerizing the English boy in their quest to recover the missing diamond. — Leighton and Surridge, 213.

As a result of the British army's storming of Seringapatam (or Srirangapatna), the capital of Mysore in southern India,in 1799, the British East India Company became the dominant political and economic power in the Indian subcontinent. Collins provides, then, an historical context for the "Romance" as he describes the novel in the title given in both Harper's Weekly and All the Year Round, reinforcing the sense of a documentary with extracts and testimonial narrativesoffered by eight different characters over the course of the story.Once the fictional John Herncastle has led his troops into the Moslem-controlled city, he becomes separated from his fellows as he makes his way to the Moghul armoury in search of the legendary Moonstone. By the time that the narrator, his cousin and fellow officer, catches up with Herncastle, he discovers the scene of slaughter where the diamond has been stored. The smoking torch, spreading pitchy smoke throughout the room, may imply the less benign aspects of imperialism. Certainly the conquest of the city seems to have given Herncastle a licence to pillage and murder.

Although the great social illustrator George Du Maurier provided a frontispiece for the 1890 Chatto and Windus edition, the first of F. A. Fraser's eight wood engravings for that edition powerfully realises Herncastle as the agent of imperialism and the remaining Brahmin as representative of the subject peoples of Africa and Asia. However, the 1868 illustration of this same scene is even more lurid and Sensational. Apparently Collins approved of the picturesque and imaginative illustrations by an anonymous American artist working in the style of Harper and Brothers' house artist John Maclenan, who had illustrated both Dickens's A Tale of Two and Great Expectations "lavishly" for that large-format American weekly magazine. Although Harper's house illustrator (or perhaps, as M. E. Leighton and Lisa Surridge contend, a pair of house illustrators) provides an even more dramatic realisation of the scene as envisaged by F. A. Fraser, A cry inside hurried me into a room, which appeared to serve as an armoury. A third Indian, mortally wounded, was sinking at the feet of a man whose back was towards me..

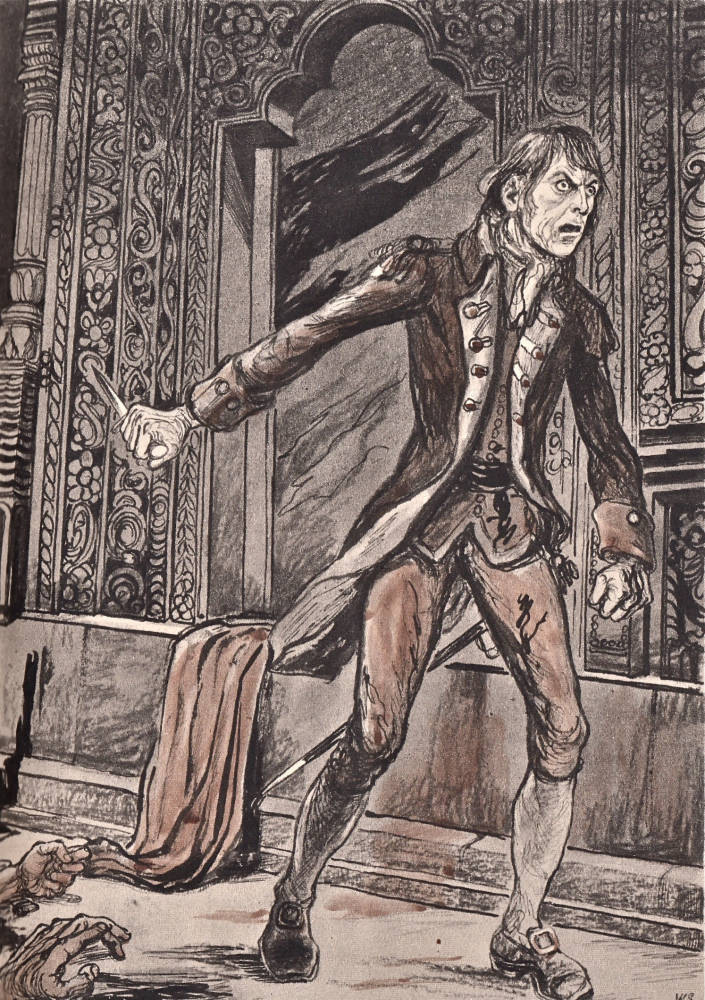

In F. A. Fraser's rendering of the scene, the third Brahmin is still pleading for his life as Colonel Herncastle's cousin, the narrator of "The Prologue," with a uncertain expression enters the room by parting the curtain, his sabre advanced. Herncastle himself, bareheaded (perhaps to suggest his departure from military discipline) stares downward at Brahamin, whose raised finger (centre) may betoken a warning. The officer grips the dagger with the gemstone in its hilt in his right hand, menacing the unarmed supplicant, as he holds aloft a torch in his left, his sword still by his side. In the 1868 illustration, the figure whom Harper's readers just after the American Civil War might have viewed as heroic in light of the recent war between the "Union" North and the "Confederate" South is revealed as obsessed by the diamond and prepared to murder any native who comes between him and the object of his desire. Colonel Herncastle in the serial is neither properly clothed (for the jacket of his uniform is partly unbuttoned, he wears no belt, and has no helmet) nor armed with standard officer's weapons (a pistol and a sabre). Indeed, the uniform in which he appears in the Harper's plate would seem to be that of an officer in the army of the American Republic rather than the type of uniform worn by British officers during the Napoleonic Wars as seen in the Fraser illustration. Perhaps, having just murdered two of the three guardians, Herncastle is dazed or disoriented; certainly he does not seem to be attending to the man at his feet, apparently making an obeisance. The South Asian who pleads from a subservient position is, in fact, the one with whom Collins would have his readers identify in terms of the purity of his motives and his sacred calling as a guardian of the Moonstone, his costume suggesting the exotic and mystical East of the Arabian Nights.

Relevant images from the 1890 to the 1946 Editions

Left: F. A. Fraser's less violent study of the scene in the Moghul armoury as the third brahmin pleads for mercy, A cry inside hurried me into a room, which appeared to serve as an armoury. A third Indian, mortally wounded, was sinking at the feet of aman whose back was towards me. (1890). Centre: A. Pearse's frontispiece which foreshadows the three priests' restraining Godfrey Ablewhite in order to recover the diamond, He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck (1910). Right: William Sharp's study of the obsessed young officer, Colonel Herncastle in the armoury (uncaptioned, 1946). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946).

- Bibliography for both Primary and Secondary Sources for The Moonstone and British India (1868-2016)

- Gallery of Headnote Vignettes by William Jewett for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly (4 January — 8 August 1868)

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August, pp. 5-529.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. With 66 illustrations. Vol. 12 (1 January-8 August 1868), pp. 5-503.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by William Jewett. New York: Harper & Bros., 1871.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone/span>. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

Harper's

Weekly

Wilkie

Collins

Next

Created 4 August 2016

Last updated 26 October 2025