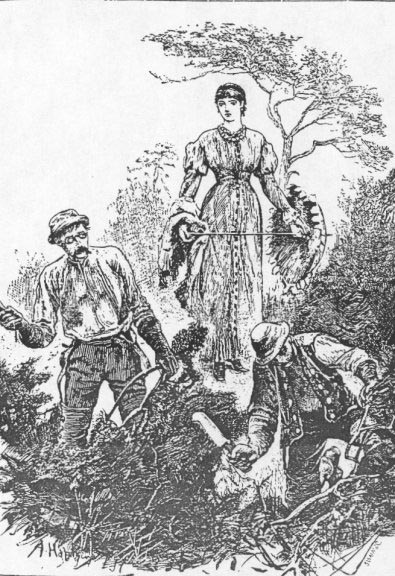

Unconscious of her presence, he still went on singing.

Arthur Hopkins

6.375 by 4.3125 inches, framed

Hardy's The Return of the Native

Belgravia XXXVI (August 1878), to face p. 238.

[Click on the illustration to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned it, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Text illustrated: Eustacia Mortified at Her Husband Clym's Demeening Occupation

On one of these warm afternoons Eustacia walked out alone in the direction of Yeobright’s place of work. He was busily chopping away at the furze, a long row of faggots which stretched downward from his position representing the labour of the day. He did not observe her approach, and she stood close to him, and heard his undercurrent of song. It shocked her. To see him there, a poor afflicted man, earning money by the sweat of his brow, had at first moved her to tears; but to hear him sing and not at all rebel against an occupation which, however satisfactory to himself, was degrading to her, as an educated lady-wife, wounded her through. Unconscious of her presence, he still went on singing: —

“Le point du jour

A nos bosquets rend toute leur parure;

Flore est plus belle à son retour;

L’oiseau reprend doux chant d’amour;

Tout célèbre dans la nature

Le point du jour.

“Le point du jour

Cause parfois, cause douleur extrême;

Que l’espace des nuits est court

Pour le berger brûlant d’amour,

Forcé de quitter ce qu’il aime

Au point du jour.”

It was bitterly plain to Eustacia that he did not care much about social failure; and the proud fair woman bowed her head and wept in sick despair at thought of the blasting effect upon her own life of that mood and condition in him. Then she came forward. [Book the Fourth, "The Closed Door," Chapter II, "He Is Set Upon by Adversities, But He Sings a Song," 232]

Commentary

Eustacia, Clym, and Humphrey on the heath in late August are framed by trees (the tall tree, stretching well above the scene, being an analogue for Eustacia's aspiring for the lights of Paris), sky, and the stubborn furze. Each figure reacts to the natural surroundings in a different manner (consistent with Hardy's entitling this series of 'Wessex' novels "stories of character and environment"), so that the plate has an almost emblematic quality. Eustacia comes across her husband and his Egdonite companion, the bumptious Humphrey, engaged in the physically-demanding (and to her, demeaning) task of cutting furze for fuel. This job is a far-cry from what Eustacia had imagined her husband doing in Paris; it is analogous to what Conrad's Marlow in "Youth" calls the "grave-diggers' work" of shovelling coal in the bilge (the text suggests ironically that Clym is like Adam after his expulsion from Eden, since both are doomed to earn their bread by the sweat of their brows). To Eustacia this sight reinforces the purgatorial nature of Egdon. Frustrated in her schemes to escape the place to which male authority (her grandfather) has consigned her, she cannot comprehend how her husband can sing his French folk-song (apparently so alien to the spirit of the heath and of his present occupation) so joyously and be at peace under such circumstances. Her goddess-like pose on the rock above the workers makes her seem to float on the air; this pose, together with her above-centre position and fashionable attire, emphasizes her superior attitude towards and emotional alienation from Clym and the heath. In her smart Paris dress and carrying an elegant parasol (which, like Lucetta Templeman's in The Mayor of Casterbridge , sets her off as an outsider, and signifies her insulation from the source of the land's strength, the Wessex sun) she is markedly out-of-place. Eustacia longs for release from this savage ground, and seems about to be born upwards. Her elevated figure suggests her emotional and intellectual apartness from Egdon and her need for a higher manner of living.

Appropriately (and as the omniscient text makes clear), Clym is oblivious to her presence, implying the breakdown in sympathy and communication that has lately occurred between déclassé husband and "lady-wife." Hopkins has illustrated the moment of detachment that precedes Eustacia's emotional outburst expressive of her indignation at Clym's embracing "social failure" by joyously engaging in "this shameful labour." Perhaps her pictured expression, in view of the feelings seething within her, is too impassive. By virtue of his goggles, furze-cutter's gloves and leggings, Clym contrasts his wife — his suspenders are down, suggesting a lowering of his gentlemanly status. Hopkins has physically subordinated Clym and Humphrey to Eustacia since both males are engulfed by the writhing vegetable life at which they slash with their knives. The goggles both serve to remind the reader of Clym's recent eye problems (acute inflammation caused by the studies related to his plans for opening a school), evoking sympathy for him, and to render him alien and unfamiliar, a far different figure from that well-dressed, polished, urbane young man of the May illustration (Hopkins' initial rendering of Clym). If Clym can be so comforted by the manual labour of a heath-dweller, his Parisian cosmopolitanism was a mere veneer — and Eustacia has fallen in love with (and, worse yet, married) a false image, unaware of the inner life of Clym's nature.

Humphrey provides the viewer with a point of reference for Clym since he is a true Egdonite, a peasant who has experienced no other place or way of life. He belongs on the heath; Eustacia does not. Humphrey is utterly engulfed in the furze branches; Clym is more aloof; Eustacia is completely detached.

The fourth figure or character in Hopkins' eighth plate is Egdon Heath itself, so significant a presence that it was the subject of Henry MacBeth-Raeburn's only illustration, the frontispiece, for the 1895 Osgoode-McIlvaine edition. Although it functions principally as theatrical backdrop, the heath is an active agent in the illustration as its tentacles surround the ephemeral trespassers. Hopkins suggests the heath's resistance to human attempts to restrain its growth and emasculate its power. Eustacia, having no roots in this land (as her hovering position implies), feels no kinship with Egdon, whereas Clym like his cousin Thomasin needs the passion of the heath and a sense of oneness with it. However, Clym's intellect, reading, and overseas experience prevent him from wholeheartedly loving the heath as Thomasin does.

As in his other illustrations for the novel, Hopkins has arranged the figures in a pyramid to stabilize the composition: Eustacia's head is the peak, the lines of her body running down to connect her to the forms of Clym and Humphrey, and the base being the ragged furze.

Related Materials

- Henry Macbeth-Raeburn's Frontispiece: Egdon Heath for the Osgoode-McIlvaine Edition (1895)

- Illustrations for the Monthly Serialisation of Thomas Hardy's The Return of the Native

Bibliography

Hardy, Thomas. Book IV, "The Closed Door." Chapters 1-4. The Return of the Native. Illustrated by Arthur Hopkins. Belgravia, A Magazine of Fashion and Amusement (London), Vol. XXXVI. August 1878. Pp. 228-256.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Towtowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Purdy, Richard Little, and Millgate, Michael, eds. The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy. Oxford: Clarendon, 1978. Vol. 1 (1840-1892).

Victorian

Web

Thomas

Hardy

Illus-

tration

Arthur

Hopkins

Next

Created 5 December 2000

Last modified 11 June 2025