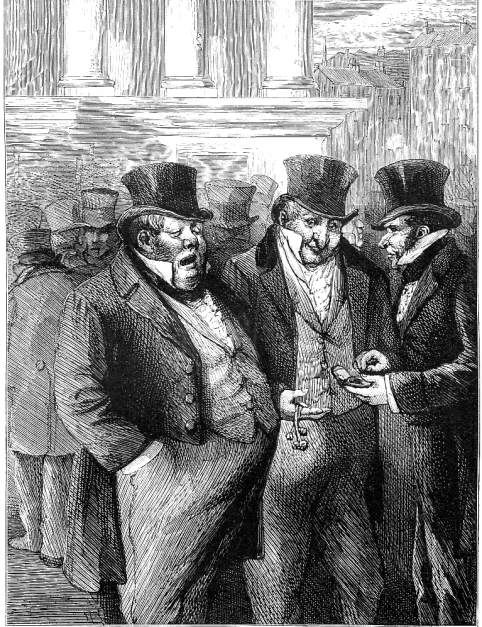

"Scrooge hears of his own death" by Charles Green (p. 106). 1912. 7.3 x 10.2 cm, vignetted. Dickens's A Christmas Carol, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (p. 15-16). Specifically, Scrooge hears of his own death has a caption that is quite different from the title given in the "List of Illustrations"; the abbreviated textual quotation that serves as the caption for this first illustration for "Stave Four" is "'No.' said a great fat man . . . . 'I don't know much about it, either way. I only know he's dead" (based on p. 106, from immediately below the illustration itself). Although John Leech has provided no equivalent illustration in "Stave Four, The Last of the Three Spirits" in the 1843 first edition of the novella, in later editions, a few illustrators have included such a scene that contemporary film adaptations have highlighted. Notably Soil Eytinge, Junior in the 1868 Ticknor and Fields edition, On 'Change and Fred Barnard in the 1878 British Household Edition illustration, This pleasantry was received with a general laugh, focus on the moment when Scrooge's business associates exchange news about an unnamed businessman's demise.

Passage Illustrated

[Scrooge and his shrouded guide] scarcely seemed to enter the city; for the city rather seemed to spring up about them, and encompass them of its own act. But there they were, in the heart of it; on 'Change, amongst the merchants; who hurried up and down, and chinked the money in their pockets, and conversed in groups, and looked at their watches, and trifled thoughtfully with their great gold seals; and so forth, as Scrooge had seen them often.

The Spirit stopped beside one little knot of business men. Observing that the hand was pointed to them, Scrooge advanced to listen to their talk.

"No," said a great fat man with a monstrous chin," I don't know much about it, either way. I only know he's dead."

"When did he die?" inquired another.

"Last night, I believe."

"Why, what was the matter with him?" asked a third, taking a vast quantity of snuff out of a very large snuff-box. "I thought he'd never die."

"God knows," said the first, with a yawn.

"What has he done with his money?" asked a red-faced gentleman with a pendulous excrescence on the end of his nose, that shook like the gills of a turkey-cock.

"I haven't heard," said the man with the large chin, yawning again. "Left it to his company, perhaps. He hasn't left it to me. That's all I know."

This pleasantry was received with a general laugh.

"It's likely to be a very cheap funeral," said the same speaker; "for upon my life I don't know of anybody to go to it. Suppose we make up a party and volunteer?"

"I don't mind going if a lunch is provided," observed the gentleman with the excrescence on his nose. "But I must be fed, if I make one."

Another laugh.

"Well, I am the most disinterested among you, after all," said the first speaker," for I never wear black gloves, and I never eat lunch. But I'll offer to go, if anybody else will. When I come to think of it, I'm not at all sure that I wasn't his most particular friend; for we used to stop and speak whenever we met. Bye, bye."

Speakers and listeners strolled away, and mixed with other groups. ["Stave Four: The Last of the Three Spirits," pages 105-107]

Commentary: "Overheard Conversation"

Having shown us the blight upon society that the capitalistic system has imposed in Ignorance and Want, Dickens now takes the reader inside the system, into the control centre, the very "heart" of the Stock Exchange and the financial system. The callousness of the overheard conversation is symptomatic of the laissez-faire system.

Although Dickens undoubtedly concurred with John Leech that, for the original edition, the image of Scrooge's overhearing the responses of his colleagues at the London Exchange to the circulating news of his death was a less significant scene than that in which Scrooge encounters his own grave, The Last of the Spirits, as the Victorian social conscience took hold in the decades following The Hungry Forties, Victorian readers relished the irony of the scene in which Scrooge's business associates respond with little other than mild interest to the death of Ebenezer Scrooge, capitalist, investor, and member of the stock exchange — but never actually name him. Readers strongly suspect that the dead man is Scrooge (this is, after all, a vision of his personal future, not just the future in general), but Scrooge does not reach the all too obvious conclusion. Rather, he expects to see his future self "in his accustomed corner" of the Exchange (appropriately in the 1951 film, "under the clock"), and is surprised when he sees another in his place.

Since the "great fat man" with the largest chin is holding forth while others gathered round (presumably in the porch of the old exchange building) listen attentively to this "captain of industry" in both the Fred Barnard and Charles Green illustrations, he is clearly the focal point of each illustration, a supreme representative of Scrooge's class. He is yawning in the Eytinge caricature of three top-hatted capitalists, but holding forth, his hands in his capacious, flowered waistcoat, conspicuously displayed his paunch as the outward and visible sign of his affluence, and therefore of his commercial enterprise and sagacity. Both Eytinge and Green have assimilated elements from the above description — trifling with seals and checking pocket-watches — with a specific moment in the group's conversation: "What has he done with his money?" asked a red-faced gentleman with a pendulous excrescence on the end of his nose, that shook like the gills of a turkey-cock. "I haven't heard," said the man with the large chin, yawning again. Whereas Eytinge has taken up the "gills of a turkey-cock" description with a vengeance, savagely ridiculing the grotesque capitalist, Green the realist merely shows him as larger and more expansive than his fellows. They are otherwise all much of a type: wearing top hats and business suits of broadcloth with period tailccoats, and carrying canes; but they are neither hideous nor repulsive; indeed, they are ordinary businessmen in Green's interpretation. However, there is no informing context as there is in Barnard's rather more theatrical illustration of the scene inside the London Exchange; Green has drawn his group of capitalists in the round, so to speak, and provide no backdrop for the vignette, so thatone must engage with text and lithograph simultaneously to understand the significance of the setting and this overheard conversation.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1868 Ticknor & Fields and the 1878 British Household Editions

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of the scene in which Scrooge overhears his business associates discussing Scrooge's demise at the Exchange, On "Change. Right: John Leech's melodramatic interpretation of the graveyard scene that culminates the fourth stave, The Last of the Spirits.

Above: Fred Barnard's interpretation of the group jocularly conversing about Scrooge's death, This pleasantry was received with a general laugh. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale UP, 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 26 August 2015