Vision of the Rag Shop: "What do you call this?" said Joe. by Charles Green (114). 1912. 11.1 x 14.1 cm, framed. Dickens's A Christmas Carol, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (15-16). Specifically, Vision of the Rag Shop has a caption that is quite different from that title, given in the "List of Illustrations"; the abbreviated textual quotation that serves as the caption for this second illustration for "Stave Four" is "What do you call this?" said Joe (based on 113, at the very top of the page preceding the illustration).

Context of the Illustration

Scrooge and the Phantom came into the presence of this man, just as a woman with a heavy bundle slunk into the shop. But she had scarcely entered, when another woman, similarly laden, came in too; and she was closely followed by a man in faded black, who was no less startled by the sight of them, than they had been upon the recognition of each other. After a short period of blank astonishment, in which the old man with the pipe had joined them, they all three burst into a laugh.

"Let the charwoman alone to be the first!" cried she who had entered first. "Let the laundress alone to be the second; and let the undertaker's man alone to be the third. Look here, old Joe, here's a chance. If we haven't all three met here without meaning it!"

"You couldn't have met in a better place," said old Joe, removing his pipe from his mouth. "Come into the parlour. You were made free of it long ago, you know; and the other two an't strangers. Stop till I shut the door of the shop. Ah! How it skreeks! There an't such a rusty bit of metal in the place as its own hinges, I believe; and I'm sure there's no such old bones here, as mine. Ha, ha! We're all suitable to our calling, we're well matched. Come into the parlour. Come into the parlour." . . .

"What odds then. What odds, Mrs. Dilber?" said the woman. "Every person has a right to take care of themselves. He always did.". . .

"Very well, then!" cried the woman. "That's enough. Who's the worse for the loss of a few things like these? Not a dead man, I suppose."

"No, indeed," said Mrs. Dilber, laughing.

"If he wanted to keep them after he was dead, a wicked old screw," pursued the woman, "why wasn't he natural in his lifetime? If he had been, he'd have had somebody to look after him when he was struck with Death, instead of lying gasping out his last there, alone by himself."

"It's the truest word that ever was spoke," said Mrs. Dilber. "It's a judgment on him." . . .

"And now undo my bundle, Joe," said the first woman. . . .

"What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?"

"Ah!" returned the woman, laughing and leaning forward on her crossed arms. "Bed-curtains." ["Stave Four: The Last of the Three Spirits," 109-113]

Commentary: "Another Overheard Conversation"

Although John Leech has provided no equivalent illustration in "Stave Four, The Last of the Three Spirits" in the 1843 first edition of the novella, in later editions, a few illustrators have included such a scene that contemporary film adaptations have exploited for its ghoulish atmosphere. Notably Sol Eytinge, Junior in the 1868 Ticknor and Fields edition, Old Joe's (see below) and Fred Barnard in the 1878 British Household Edition illustration, "What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?" (see below) focus on the moment when Ebenezer Scrooge's cleaning lady, the laundress, and the undertaker's man enact Scrooge's capitalistic ethos. Visually, these "rag-and-bone shop" scenes are an extension of the poverty and deprivation evident in the well-known Ignorance and Want Leech wood-engraving at the close of the fourth stave.

Seemingly Dickens now takes readers a world away from the London Exchange, the textual backdrop for the previous illustration. In reality, the rag-and-bone dealer's is not so many city blocks away from the 'Change, in a notorious district such as Limehouse, Shoreditch, or the Seven Dials (the settings for the London underworld in Oliver Twist), a group of aspiring capitalists gather for a discussion of Scrooge's death and for another business transaction (converting Scrooge's personal property into ready cash), enacting the ethos of the capitalistic system as a shocked and disgusted Scrooge looks on. Two decades ahead of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species, the quartet exemplify "Survival of the Fittest." In the urban jungle, the jackals gather to despoil the corpse.

Dickens undoubtedly concurred with Leech that, for the original edition, the image of Scrooge's overhearing the dialogue of his cleaning-lady and laundress at the marine store shop was a less significant scene than that in which Scrooge encounters his own grave, The Last of the Spirits. Again, as at the Exchange, readers strongly suspect that the dead man is Scrooge (after all, how many other single men did the laundress and the char lady work for?), but Scrooge again does not recognise who the dead man thus despoiled must be.

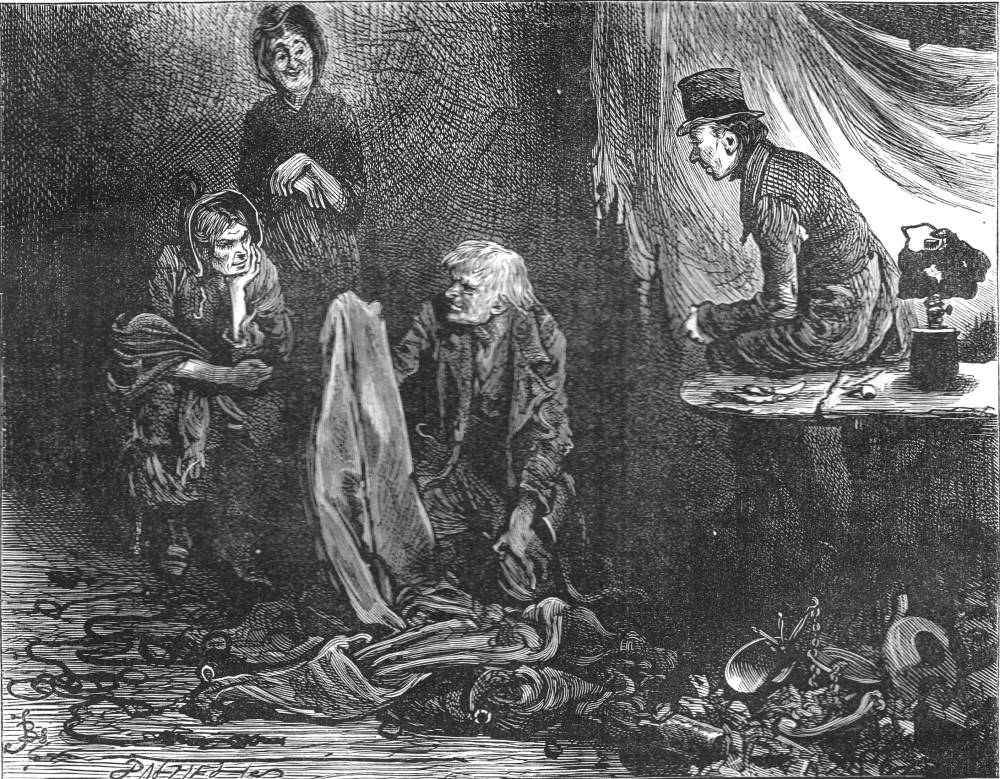

Green's approach is somewhat different from that of Eytinge's close-up in the 1868 edition and the character studies of Barnard in the British Household Edition of 1878. Rather, Green casts the scene as a dark plate in the manner of Hablot Knight Browne in Dombey and Son and Bleak House. The darkness here is both the intensifying mystery for Scrooge and the bleakness of his fate — the darkness of the grave. The only figure whom Green distinguishes is the proprietor of the shop, Old Joe himself, in cloth cap and second-hand great-coat (right), his face highlighted by the kerosene lamp on the table. The faces of the laundress and char lady stand out in the darkness, but the undertaker's man is barely visible. Thus, Green's approach is far different when one compares his interpretation of the scene to Barnard's, which was surely Green's inspiration and immediate source. There is a general absence of the tendency towards hideous caricatures of Eytinge or the genial camaraderie of Barnard's human vultures. Whereas Barnard shows not only each of the characters clearly but also the scrap metal on the floor of the shop, Green embues the place with a sense of mystery; moreover, the darkness of the lithograph drives the reader back to Dickens's text after attempting to discern objects in the background — a curtain or blanket on a line dividing the front of the shop from the "parlour" and the scrap-metal on the floor (left) as Old Joe, pipe in his mouth, coolly appraises the curtains. In none of these plates does one see Scrooge or his spirit guide, so one naturally assumes that the reader is seeing what they are seeing, and hearing in the text what they are hearing.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1868, 1878, 1905, and 1915 Editions

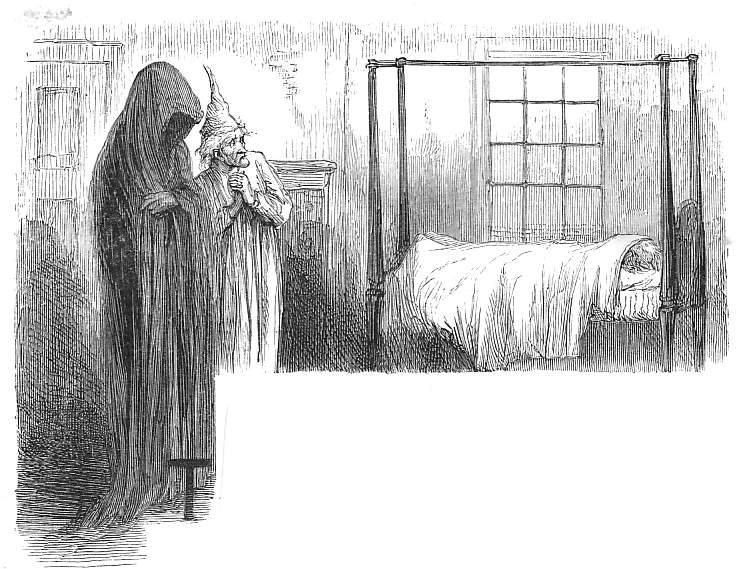

Left: Eytinge's interpretation of the scene in which Scrooge's service-providers discuss his death — and pawn his belongings, Old Joe's. Centre: Eytinge's headpiece for the fourth stave, Death's Dominion (1868). Right: Arthur Rackham's equally grisly realisation of the pawning of Scrooge's personal property, "What do you call this?" said Joe. (1915)

Above: Barnard's interpretation of the group who served Scrooge in life now profiting from his death, "What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?" (1878)

Above: Charles E. Brock's interpretation of the same scene as Joe looks for signs of wear in the sheets in order to knock down the price, "What do you call this?" said Joe. (1905)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale UP, 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by Charles Edmund Brock. London: J. M. Dent, and New York: Dutton, 1905, rpt. 1963.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 26 August 2015

Last modified 11 March 2020