Meg and Lilian

Charles Green

c. 1912

8.3 x 7.3 cm, vignetted

Dickens's The Chimes, The Pears' Centenary Edition, II, 112.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Charles Green —> The Chimes —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

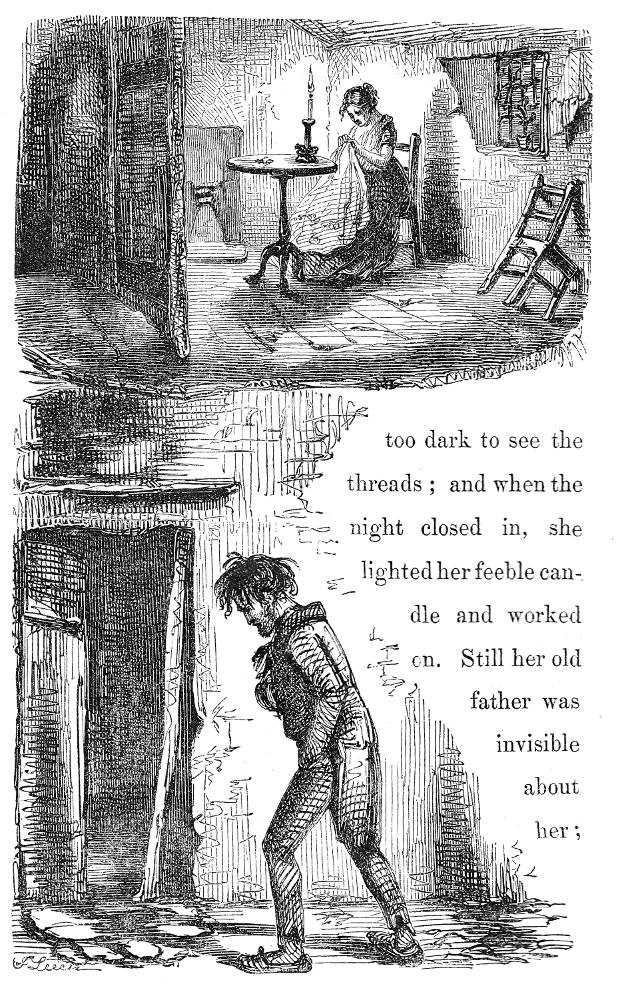

Meg and Lilian

Charles Green

c. 1912

8.3 x 7.3 cm, vignetted

Dickens's The Chimes, The Pears' Centenary Edition, II, 112.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

She saw the entering figure; screamed its name; cried "Lilian!"

It was swift, and fell upon its knees before her: clinging to her dress.

"Up, dear! Up! Lilian! My own dearest!"

"Never more, Meg; never more! Here! Here! Close to you, holding to you, feeling your dear breath upon my face!"

"Sweet Lilian! Darling Lilian! Child of my heart — no mother's love can be more tender — lay your head upon my breast!"

"Never more, Meg. Never more! When I first looked into your face, you knelt before me. On my knees before you, let me die. Let it be here!"

"You have come back. My Treasure! We will live together, work together, hope together, die together!"

"Ah! Kiss my lips, Meg; fold your arms about me; press me to your bosom; look kindly on me; but don't raise me. Let it be here. Let me see the last of your dear face upon my knees!"

O Youth and Beauty, happy as ye should be, look at this! O Youth and Beauty, working out the ends of your Beneficent Creator, look at this!

"Forgive me, Meg! So dear, so dear! Forgive me! I know you do, I see you do, but say so, Meg!"

She said so, with her lips on Lilian's cheek. And with her arms twined round — she knew it now — a broken heart.

"His blessing on you, dearest love. Kiss me once more! He suffered her to sit beside His feet, and dry them with her hair. O Meg, what Mercy and Compassion!"

As she died, the Spirit of the child returning, innocent and radiant, touched the old man with its hand, and beckoned him away. [Closes "The Third Quarter," 113-14, 1912 edition]

Neither The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In (1844) has no precise equivalent for this scene, which follows that in which Richard, dissolute and dispirited, visits Meg, who supports herself with her needle, in Richard and Margaret (see below). However, in his fourth illustration for the novella in the Household Edition anthology of 1878, Fred Barnard realised the same scene as Green's, set in Meg's garret (as the reader may judge fro contextual details that Barnard has supplied) in much the same melodramatic manner, with Meg as a forgiving mother who is welcoming home her prodigal daughter. The picture obliquely alludes as does the text to Christ and Mary Magdalene, reminding us that Lilian has had to stoop to prostitution to survive while her uncle, Will Fern has been in prison for arson.

The melodramatic dialogue of heightened emotion (signalled by repetition, apostrophe, and periodic sentences of staccato effect) between the young women is the subject of both Fred Barnard's and Charles Green's study of Meg and Lilian. Meg is above, in black, mourning her father's death nine years before, and the fallen but repentant woman, Lilian, about to die, is a contrasting figure in a light-coloured dress and bonnet. Perhaps John Leech felt that the scene was simply too graphic for a Christmas Book, but social realists Barnard and Green have not flinched in dealing with an issue that Dickens was to explore in greater depth with Little Em'ly and Martha in David Copperfield. In "Time and the City in The Chimes," Alexander Welsh emphasizes how the trajectory of the noble working-class characters — Richard, Margaret, Lilian, and Will — is conditioned by the "theory of social causation" (10). According to this theory, which Dickens had rejected in the career of the protagonist of Oliver Twist (whose victory over Monks and Fagin signalled the triumph of heredity over environment), poverty and social injustice will inevitably blight the lives of fundamentally decent working-class people, driving them into vice, crime, and untimely death. This pessimistic principle governs the compassionate Trotty's Dantesque vision of the suffering of those whom he has known in life who have fallen prey to these negative forces unleashed by the mass unemployment, dislocation, homelessness, and deprivation of The Hungry Forties. As Welsh has noted, "A person of Margaret Veck's poverty and good looks would very likely become a prostitute and eventually take her own life" (10). In the story as we have it, Lilian rather than Margaret dies — and not by her own hand — after descending into prostitution, while the older Margaret (clearly something of a mother-figure to Lilian in Dickens's text and the original illustrations) maintains a domestic hearth and industriously plies her needle: "Dickens and his contemporaries were fascinated by the juxtaposition of fallen and unfallen women because they represented the basic antithesis in modern life between the city (women of the streets, so called) and the family gathered about the fire (even a mother, wife, and daughter combined in one person)" (Welsh, 12).

Green, like Barnard, then, presents a sharp contrast between the two young women, with blond-haired Lilian (her back to the viewer in the 1878 study, but fully visible to the reader in the 1912 version as Green compels the reader to identify with her) kneeling in contrition before the darker haired, "respectable" Margaret, in mourning dress and white apron (necessary for one who plies her trade), stooping to support and by implication forgive her. Although apparently binary opposites, they represent the choices available to young, working-class women in the absence of other vocational opportunities and marriage in a challenging economic environment.

Whereas Barnard includes in the background sewing on the table and a fireplace, Green has eliminated such background details to focus the reader's attention on the two figures, thrown into chiaroscuro by the intense shadow that dominates the right side of the plate, implying perhaps the gloomy future that attends both young women and the social opprobrium both face as outcasts from "respectable" society. Blonde Lilian is, as it were, in the spotlight, every detail of her face, dress, and hair accentuating her youth and paleness. In his 1910 re-interpretation Harry Furniss has not attempted this compelling scene that points to the context in which Dickens wrote the tale. Both Barnard and Green in their characterizations of Lilian emphasize her child-like youth and innocence in denial of society's regarding her as a worthless outcast, a "Magdalene" — hence, both illustrators focus focus on her luxuriant hair, recalling how Mary Magdalene dried the feet of Jesus Christ after washing them.

Left: John Leech's scene that reveals to Trotty what became of his daughter and her fiancé nine years after his death, Richard and Margaret. Right: Harry Furniss's study of Trotty's seeing the same scene, Margaret and Richard.

Above: Fred Barnard's 1878 wood-engraving of Lilian's return to Meg to ask her foregiveness, and melodramatically to die in her arms, "Never more, Meg; never more! Here! Here!"

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes. Introduction by Clement Shorter. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Pears' Centenary Edition. London: A & F Pears, [?1912].

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. (1844). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. 137-252.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-18.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Welsh, Alexander. "Time and the City in The Chimes." Dickensian 73, 1 (January 1977): 8-17.

Created 13 April 2015

Last modified 25 February 2020