"Never more, Meg; never more! Here! Here!"

Fred Barnard

1878

framed 13.7 x 10.6 cm (5 ⅜ by 4 ⅛ inches), framed (p. 68).

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Fred Barnard —> Christmas Books —> Next]

"Never more, Meg; never more! Here! Here!"

Fred Barnard

1878

framed 13.7 x 10.6 cm (5 ⅜ by 4 ⅛ inches), framed (p. 68).

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

You may use this image, and those below, without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

The original version of the 1844 novella that Dickens read to his friends in John Forster's rooms at Lincoln's Inn Fields on the evening of Tuesday, 2 December, was far more pessimistic about the fates of Lilian Fern and Meggy Veck than the final version, in which Meg has married Richard belatedly and given birth to a sickly but legitimate child. The artist Daniel Maclise, one of the fortunate auditors, recorded the reading as a pencil drawing that alluded to Da Vinci's The Last Supper (including a halo playing over the reader's head), but this dual study of Meggy Veck and Lilian Fern is one of the few Barnard illustrations consistent with this spiritual aspect of the original series of plates dropped into the text.

Dickens's intention in The Chimes, as he wrote to Forster from Italy, was to "strike a blow for the poor," and consequently he "pulled no punches" in depicting the sufferings of the story's young, working-class women. Meg and Lilian attempt to survive as seamstresses, but Meg in the version read aloud that December evening has a child out of wedlock, and Lilian eventually turns to a life of prostitution in this text for the Hungry Forties.

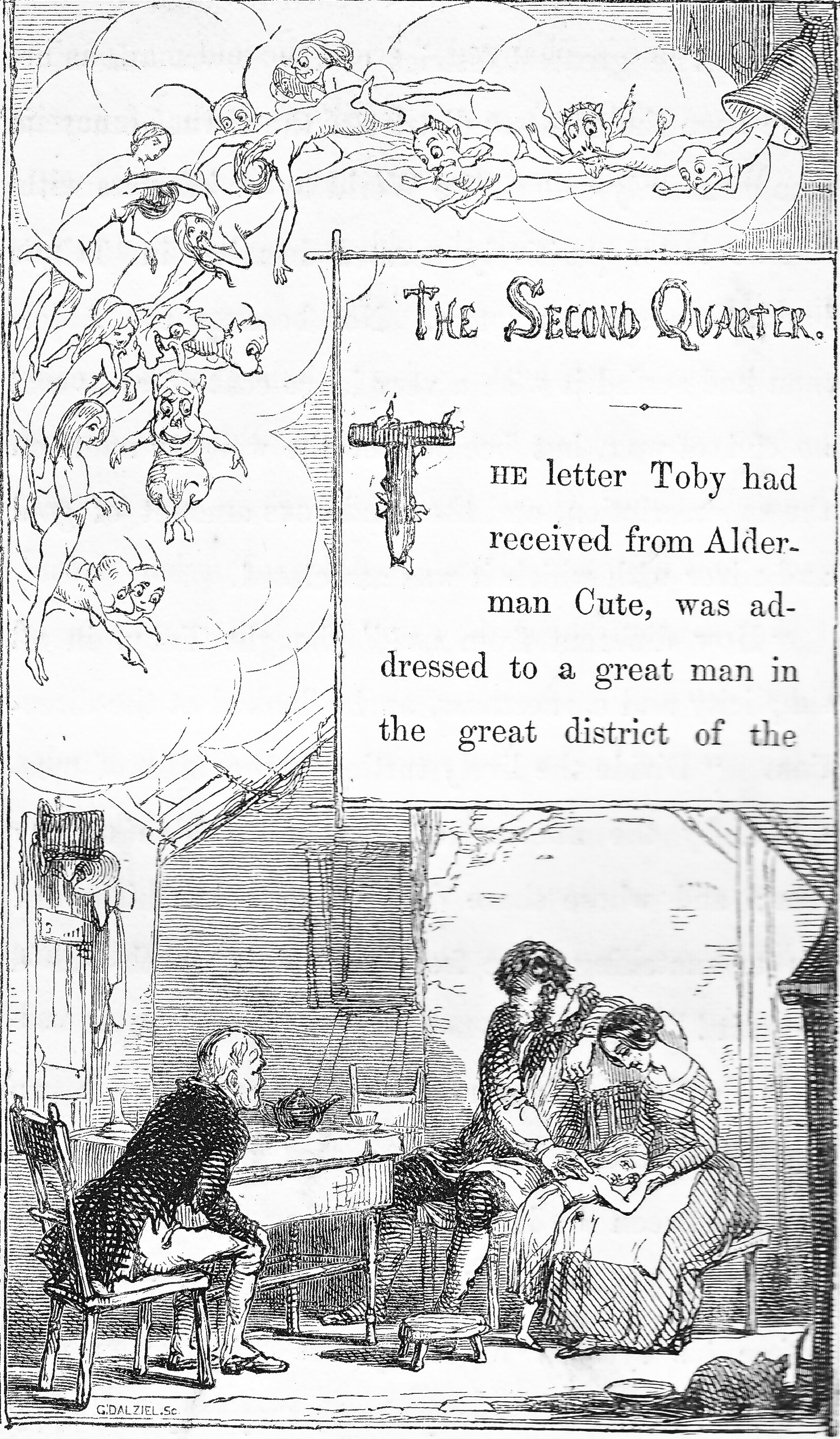

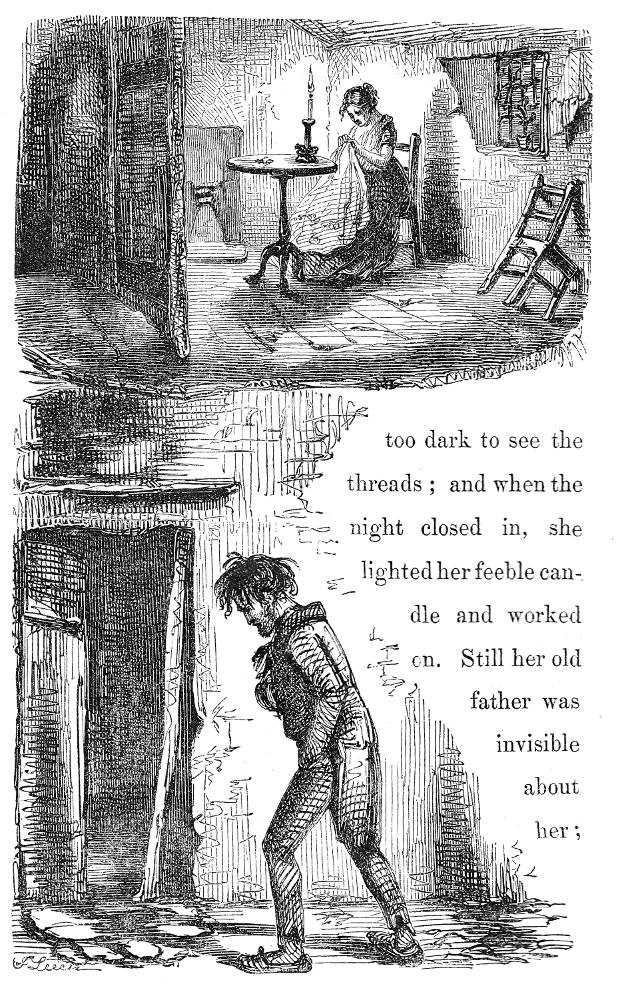

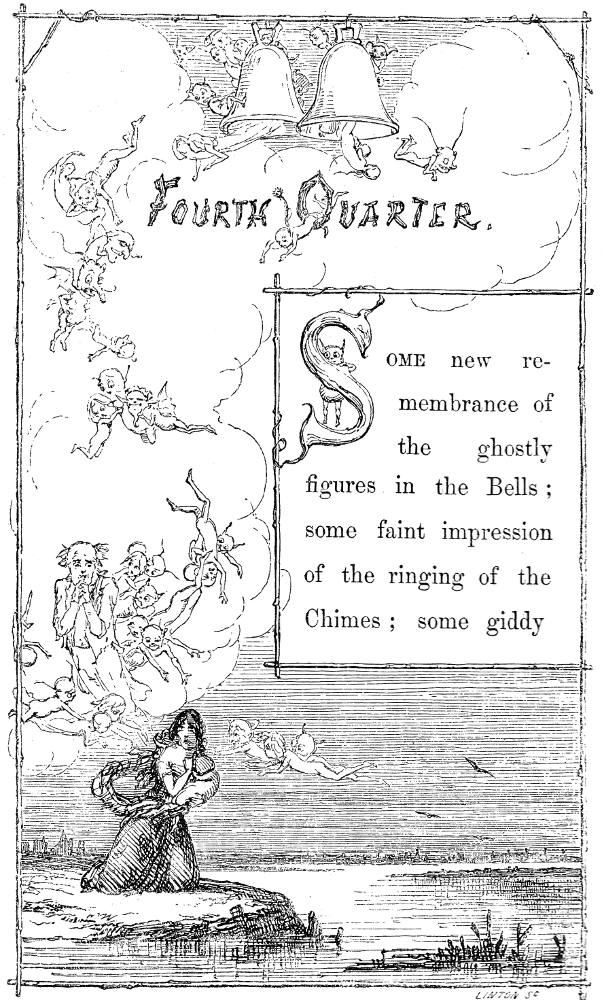

Three illustrations of Margaret and Lilian from the original 1844 edition: Left: Doyle's Trotty at Home; centre: Leech's Richard and Margaret; right: Doyle's Margaret and Her Child.

Trotty witnesses his destitute daughter on the verge of throwing herself and her infant into the wintery Thames (the resting place of many a prostitute) in Margaret and Her Child (1844). However, Doyle has subordinated her figure to that of the dreamer and the outlandish figures of the goblins, shown in outline and therefore as mere spirits unable to intervene in the actions of the living, so that her putative act rather than her motivation is the focus of Doyle's fanciful composition. The presence of Trotty's ghost and the cavorting goblins detracts from the severity of the social message. What Margaret was before destitution made her desperate Doyle has indicated in Trotty at Home. The small-scale vignette of Meg in Trotty's hovel shows a young woman in a demure dress with a large, white apron looking after Lilian as a child. Later, in Trotty's vision, Margaret kneels on the bank of the river, holding a very tiny infant as she looks toward the reader while immediately above her, powerless to assist or intervene, are her father and a group of anguished goblins. Dickens blames the ranting of Alderman Cute against marriage among the poor for Meggy's fate — as Lilian tells Richard, "Others stepped in between you; fears, and jealousies, and doubts, and vanities, estranged you from her; but you did love her, even in my memory!" ("Third Quarter"; Household Edition, p. 66).

The arrival of Richard with a message for Meg from Lilian, earning her living from prostitution and therefore living apart from Meg, is the subject of Leech's 1844 dual illustration Richard and Margaret, in which a down-and-out Richard (below), ill-shaved and stooping, approaches Meg's garret (above). As in Thomas Hood's poem "The Song of the Shirt", Meg is working on a gentleman's cotton shirt by candlelight in a cutaway room suggestive of a theatrical set. Leech has minimised the figure of the seamstress to focus on the formerly robust blacksmith, Richard, who, being closer to the reader, is much larger. The seamstress concentrates on her task, focussing on her stitching, while the disreputable Richard, having lost his hopes and his occupation, barely seems to recognize his surroundings as his gaze is turned inwards. The melodramatic dialogue of heightened emotion (signalled by repetition, apostrophe, and periodic sentences of staccato effect) that follows Richard's visit is the subject of Fred Barnard's study of Meg (above, in black, mourning her father's death) and the fallen but repentant woman, Lilian, about to die:

In any mood, in any grief, in any torture of the mind or body, Meg's work must be done. She sat down to her task, and plied it. Night, midnight. Still she worked.

She had a meagre fire, the night being very cold; and rose at intervals to mend it. The Chimes rang half-past twelve while she was thus engaged; and when they ceased she heard a gentle knocking at the door. Before she could so much as wonder who was there, at that unusual hour, it opened.

Oh, Youth and Beauty, happy as ye should be, look at this! Oh, Youth and Beauty, blest and blessing all within your reach, and working out the ends of your Beneficent Creator, look at this!

She saw the entering figure; screamed its name; cried "Lilian!"

It was swift, and fell upon its knees before her: clinging to her dress.

"Up, dear! Up! Lilian! My own dearest!"

"Never more, Meg; never more! Here! Here! Close to you, holding to you, feeling your dear breath upon my face!"

"Sweet Lilian! Darling Lilian! Child of my heart no mother's love can be more tender lay your head upon my breast!"

"Never more, Meg. Never more! When I first looked into your face, you knelt before me. On my knees before you, let me die. Let it be here!" ["Third Quarter"; Household Edition, p. 66]

In "Time and the City in The Chimes," Alexander Welsh emphasizes how the trajectory of the noble working-class characters — Richard, Margaret, Lilian, and Will — is conditioned by the "theory of social causation" (10), namely that poverty and social injustice blight the lives of fundamentally decent people, driving them into vice, crime, and untimely death. This principle governs Trotty's vision of the suffering of those whom he has known in life who have fallen prey to these negative forces of The Hungry Forties.

The dream vision adumbrates the future in four dramatic scenes. They are rather grim scenes, too, considering that this is a book for family reading at Christmas (though a good deal of sentiment percolates through the innuendo with which the subjects of prostitution and death are narrated). In the first scene, nine years after the opening action, Lilian is breaking away from Meg's protection — their respective ages must be eighteen and twenty-nine — and is about to become a prostitute. The marriage of Meg and Richard has never taken place . . . . In the third [scene], Lilian has left Meg's impoverished fireside and Richard is revealed as a "slouching, moody, drunken sloven, wasted by intemperance and vice" (p. 134). He recounts how Lilian has repeatedly met him in the streets and begged him to take money, the proceeds of her prostitution, to Meg. She refuses it, of course. At the close of the scene Lilian herself arrives with the purpose of dying in Meg's arms, in a posture — as she herself points out — resembling that of Mary Magdalene with Christ. [Welsh, 9-10]

Dickens, as a co-sponsor between 1847 and 1859 of banking heiress Angela Burdette Coutts's Urania Cottage at Lime Grove, Shepherd's Bush (a charitable institution intended to facilitate the rehabilitation and resettlement of "Fallen Women"), was in 1846 already very much concerned with the issue of urban prostitution. His work on the Urania project is directly reflected in his treatment of Martha and Emily in David Copperfield (1849-50). With the added advantage of having read the entire Dickens canon and Forster's Life of Charles Dickens well before he received Chapman and Hall's commission to illustrate the Household Edition of both David Copperfield and the Christmas Books, Barnard — unlike Doyle and Leech in 1846 — knew the significance for the socially conscious Dickens of these scenes of extreme poverty and moral degradation in Trotty's dream-vision. Barnard has therefore has focussed on Lilian as a type of Magdalene, rather than transferring that role to the young mother, Meg, as Doyle has done in Margaret and Her Child, even though, as Welsh notes, "A person of Margaret Veck's poverty and good looks would very likely become a prostitute and eventually take her own life" (10). In the story as we have it, Lilian rather than Margaret dies — and not by her own hand — after descending into prostitution, while the older Margaret (clearly something of a mother-figure to Lilian) maintains a domestic hearth and industriously plies her needle:

Dickens and his contemporaries were fascinated by the juxtaposition of fallen and unfallen women because they represented the basic antithesis in modern life between the city (women of the streets, so called) and the family gathered about the fire (even a mother, wife, and daughter combined in one person). [Welsh, 12]

Barnard, then, presents a contrast between the two young women, with blond-haired Lilian (her back to the viewer) kneeling in contrition before the darker haired, "respectable" Margaret, her sewing on the table and her mourning dress (despite the fact that nine years have supposedly passed since Trotty's death) being the outward and visible signs of her inner grace. The room is engulfed in the shadows of poverty, privation, and death, and yet Barnard highlights Lilian's hair (centre), Meg's hands, and the area immediately above the hearth, which is apparently the room's only source of light. Comforting the girl who is both like a sister and a daughter to her, the mature Meg leans over Lilian as she offers her the moral redemption of honest labour, sisterly affection, and companionship as an alternative to life on the streets. Asking for and receiving forgiveness, Lilian dies (as much of a broken heart as some sexually-transmitted disease or consumption) in Margaret's embrace just after the moment that Barnard has realised.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in the Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Daniel Maclise. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844 [Printed title-page dated "1845."].

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes. Christmas Books. 22 vols. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII. Pp. 38-76.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year out and a New Year in. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. Charles Dickens: The Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 1: 137-266.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Maclise, Daniel. "Charles Dickens reading 'The Chimes' to his friends in John Foster's chambers." 1844. Accessed 3 June 2012. The Victoria and Albert Museum (gift of John Forster). http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/ O1041098/charles-dickens-reading-the-chimes-drawing-daniel-maclise

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. University of California at Santa Cruz.: The Dickens Project, 1991. Rpt. from Oxford U. p., 1978.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to The Chimes." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 1: 261-266.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Welsh, Alexander. "Time and the City in The Chimes." Dickensian 73, 1 (January 1977): 8-17.

Created 8 August 2012

Last updated 27 December 2025