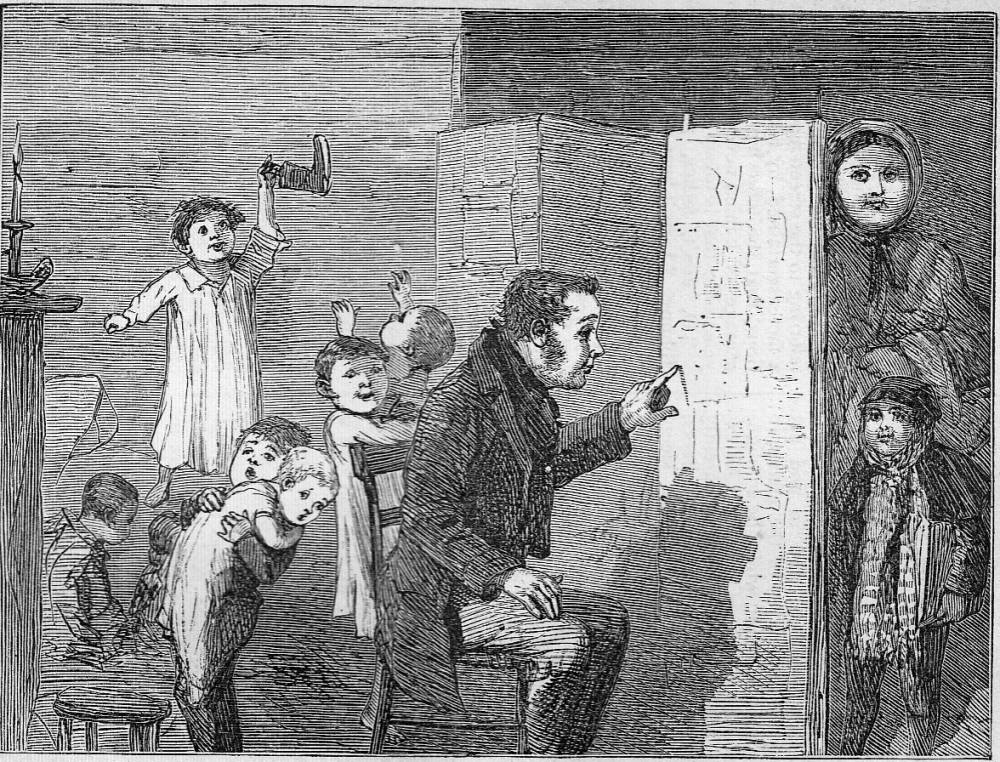

"The Tetterbys", the seventh full-page illustration for the volume by Sol Eytinge, Jr. 7.4 cm high by 9.9 cm wide. The Diamond Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867; rpt., James R. Osgood, 1875). Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Realised

Mr. Tetterby sought upon his screen for a passage appropriate to be impressed upon his children's minds on the occasion, and read the following: —

"'It is an undoubted fact that all remarkable men have had remarkable mothers, and have respected them in after life as their best friends.' Think of your own remarkable mother, my boys," said Mr. Tetterby, "and know her value while she is still among you!"

He sat down again in his chair by the fire, and composed himself, cross-legged, over his newspaper. ["Chapter Two: The Gift Diffused," p. 193]

This passage depicted or realized by other illustrators:

Leech's exuberant cartoon versus Barnard's modelled group portrait and Abbey's more prosaic treatment: left: Leech's "The Tetterbys"; centre, Leech's "Johnny and Moloch"; and, right, Abbey's realistic "'You bad boy!' said Mr. Tetterby".

The above versions of the Tetterbys by illustrators other than Eytinge make clear that the focus of the Diamond Edition's wood-engraving is character study rather than narrative exposition or elaboration of setting (details of which are minimal in his illustration). Whereas in "The Tetterbys" in the original 1848 Bradbury and Evans edition, John Leech has attempted to group the entire Tetterby clan around a diminutive table at dinner time, conveying an impression of congested space and close living conditions with the small fireplace, insufficient table, inadequate floor space, Eytinge has been able to dispose of his nine figures more comfortably. He achieves this effect by not attempting to show too much and by focussing on Mr. Tetterby and his screen, while he seems oblivious to the antics of the children behind him. Eytinge seems to be conveying his impression of the first two pages of the second chapter, but in fact has captured the very moment before the put-upon newsagent issues "a general proclamation" to the children, and just prior to Johnny's sitting on the stool (far left).

Looking a good deal like Sol Eytinge's own Bob Cratchit in "Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim", the frontispiece for the entire 1867 volume, Adolphus Tetterby here is more consistent with the "good-hearted, struggling, little newsagent" (Bentley et al., 258) that John Leech gives us in "The Gift Diffused" (p. 68) and a figure far more congruent with Dickens's text than the realistically modelled illustration by E. A. Abbey in the next decade. Using several models from the 1848 novella, Eytinge has nevertheless provided his American readers of 1867 with a more realistic and less cartoonish version of the lower-middle-class family that corresponds in its domestic felicity to the Cratchits in the original Christmas Book. In contrast, E. A. Abbey's chiding father is a far cry from mild-mannered Bob Cratchit.

Interestingly, Eytinge introduces the comic and sentimental subplot ahead of the main (melodramatic) plot involving the distribution and consequences of chemistry professor Redlaw's dubious "gift" in The Haunted Man. For the last of the Christmas Books, Eytinge, feeling that he could devote two of the eight allotted Christmas Book illustrations to the twenty-year-old text, created two scenes with visual interest. However, in focussing on Mr. Tetterby and Redlaw, Eytinge neglected the sentimental and quasi-religious thread of the story dealing with the angelic college servant, Milly Swidger, and the poor student, Edmund Longford (alias "Denham"). In "The Tetterbys," Eytinge has combined aspects of two of the original 1848 illustrations, John Leech's "The Tetterbys" and "Johnny and Moloch". Eytinge's version is especially successful at capturing the single-minded concentration of Adolphus Tetterby as he reads his news-screen, but fails to distinguish the various children (except Johnny and his charge) and to render Sophia Tetterby (right) of any interest.

Eytinge shows seven children, Leech eight, as occupying the small parlour behind the newsagent's shop. Eytinge's Tetterby looks comparatively unruffled compared to Leech's, but his children — like Leech's — bear a marked family resemblance in their facial features. Conversely, in his sole Tetterby illustration for the British Household Edition (1878) Fred Barnard in "It roved from door-step to door-step, in the arms of little Johnny Tetterby, and lagged heavily at the rear of troops of juveniles who followed the Tumblers," etc. entirely avoids the parents and their place of business and focuses entirely upon the host of children who overflow the street outside the Jerusalem buildings.

American illustrator E. A. Abbey in the Harper and Brothers Household Edition focuses on the relationship between Adolphus Tetterby, his son Johnny, the baby-minder, and the Moloch of a baby, Sally, in "'You bad boy!' said Mr. Tetterby" in a fashion at once more natural and more serious than Eytinge's, which thus blends realism with humour and character study rather the other nineteenth-century illustrations alluded to. Of his six illustrations for the same novella, Harry Furniss, following Leech's practice sixty years earlier, realised both "Tetterby's Temper" and "The Tetterby's Baby," but failed to achieve a comic effect, in spite of his far superior modelling of the figures. Leech's and Eytinge's plates enlist the reader's sympathy for both Johnny and his harassed father, whereas Barnard's engraving merely establishes the fact that the area around the Jerusalem Buildings, overrun with children, is pandaemonium.

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Rpt., Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain (1848). Il. John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Winter, William. "Charles Dickens" and "Sol Eytinge." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 181-207, 317-319.

Last modified 2May 2013