Tackleton's Wedding Day! by Harry Furniss. 1910. 9 cm high x 13.7 cm wide. Dickens's Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing VIII, 225. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated

"Why, what the Devil's this, John Peerybingle!" said Tackleton. "There's some mistake. I appointed Mrs. Tackleton to meet me at the church, and I'll swear I passed her on the road, on her way here. Oh! here she is! I beg your pardon, sir; I haven't the pleasure of knowing you; but if you can do me the favour to spare this young lady, she has rather a particular engagement this morning."

"But I can't spare her," returned Edward. "I couldn't think of it."

"What do you mean, you vagabond?"said Tackleton.

"I mean, that as I can make allowance for your being vexed,"returned the other, with a smile, "I am as deaf to harsh discourse this morning, as I was to all discourse last night."

The look that Tackleton bestowed upon him, and the start he gave!

"I am sorry, Sir," said Edward, holding out May's left hand, and especially the third finger; "that the young lady can't accompany you to church; but as she has been there once, this morning, perhaps you'll excuse her." ["Chirp the Third," 236]

Commentary

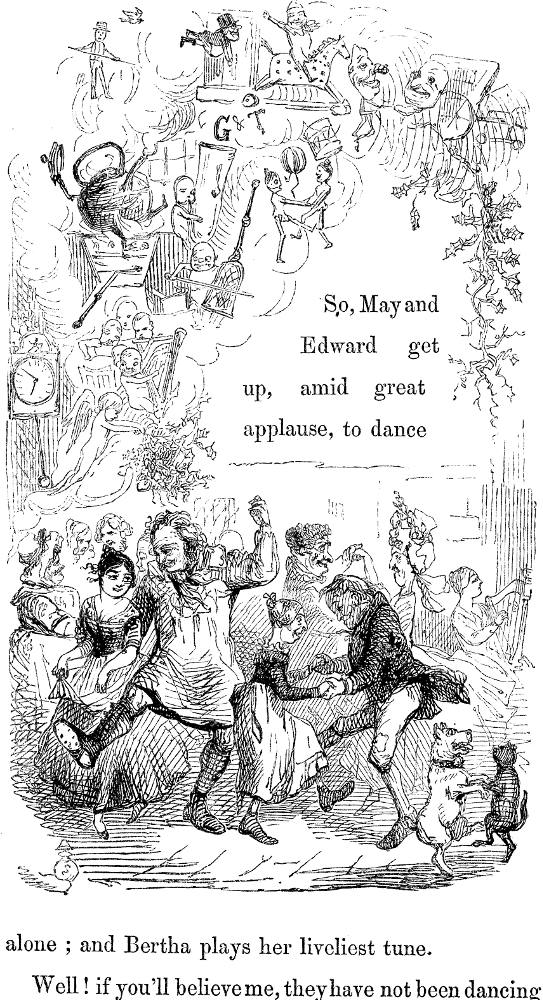

Although Furniss may not have been aware of Dickens's dissatisfaction with Leech's final contribution to the original program (disliking Leech's representation of the Carrier as disproportionately large and ugly), the early twentieth-century illustrators must have judged the original edition's ultimate plate (see right), The Dance, somewhat theatrical. Although certainly modelled on the concluding illustration for The Chimes, The New Year's Dance and on a long tradition of comedies ending with such a scene that brings all the characters together in pairs, Furniss looked for a suitable concluding scene that would emphasise comedic Nemesis rather than the kind of pairing that Leech so delightfully stage-managed in the novella's finalé.

Furniss has chosen to juxtapose the bulky, imposing figure of the fashionably-dressed, middle-aged "gentleman," the exploitative employer Tackleton, against the others in the story, who present a uniform block to the left of the somewhat theatrical set. Although the original image of Tackleton in The Dance bears little resemblance to later images by E. A. Abbey and Fred Barnard in the Household Edition volumes, all of these detached, sarcastic observers have at least one thing in common: their fashionable, bourgeois clothing that separates them instantly from the working-class figures. The dancer with the large head and curly hair dancing with Mrs. Fielding in Leech's plate is blocked by Caleb and Tilly in the foreground, so that little of his apparel is visible.

Curiously, despite his significance as a blocking figure, this is Tackleton's only appearance in the original sequence of fourteen illustrations: a mere "thumbnail" presence. However, the Household Edition illustrators thirty years later clearly understood how his machinations affect the romantic marriage plot and that, as the embodiment of a socially negative attitude, Tackleton requires both correction and reintegration. Furniss's interpretation is interesting at a number of levels: Tackleton is a social isolate, deviant in his attitude, and inclined to use his position as employer and wealthiest denizen of the village to exploit and dominate those around him, including those most vulnerable members of village society, the indigent Plummers and fatherless May Fielding. In Furniss's final illustration, despite his flamboyance and self-confidence, Tackleton is compelled to acknowledge that the younger generation has outwitted him as he deposits the wedding band with the "gob-smacked" Tilly (right).

The Enigmatic Figure of Tackleton, The Tempter

There is more than a whiff of Brimstone about Tackleton, the sarcastic and unsympathetic employer who reprises the initial persona of Ebenezer Scrooge in the first of the Christmas Books. Appealing to the Victorian social conscience in the second of the series, The Chimes (1844), Dickens found himself with no shortage of Benthamite and Malthusian villains — Alderman Cute, Sir Joseph Bowley, and the statistician Filer all admirably represent the forces opposed to improving the lot of the working class. However, since he had decided to abandon such controversial issues as prostitution and incendiarism in the third of the series, Dickens found himself short of villainous material, in spite of having an admirable lower-middle-class protagonist, John Peerybingle.

Incidental to the main plot issue — Dot's supposed adultery with the old stranger who is in fact a handsome youth in disguise — is the matter of Tackleton's forcing an engagement upon May Fielding, who has been pining for her sailor-lover lost at sea, Edward Plummer. With Edward's sister and father, the toy-makers Bertha and Caleb Plummer, he reveals himself to be a somewhat callous employer who disregards the welfare of his employees in order to turn a profit. However, Dickens's portrait of an exploitative capitalist falls short of his detailing the vices of the miser of the 'Change, Ebenezer Scrooge. That Tackleton's gruffness is but superficial is implied in the ease with which (without much motivation) he experiences a change of heart in the final scene and is welcomed back into the community at festival.

The original illustrators — Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Edwin Landseer, and Clarkson Stanfield — apparently were not inspired by the sardonic capitalist, who appears briefly in just the final illustration, The Dance by John Leech. A curmudgeon without conviction, a mere plot device and "domestic ogre, who had been living on children all his life, and was their implacable enemy" ("Chirp the First," 83 in the American Household Edition), Tackleton is a pasteboard villain, as undeveloped and one-dimensional as the blocking figures of pantomime — or nearly so, as Dickens makes clear in his introduction of the long-lost sailor's romantic rival, an exploitative capitalist who is undeserving of any sympathy, even when May Fielding jilts him:

Tackleton the Toy-merchant, pretty generally known as Gruff and Tackleton — for that was the firm, though Gruff had been bought out long ago; only leaving his name, and as some said his nature, according to its Dictionary meaning, in the business — Tackleton the Toy-merchant, was a man whose vocation had been quite misunderstood by his Parents and Guardians. If they had made him a Money Lender, or a sharp Attorney, or a Sheriff's Officer, or a Broker, he might have sown his discontented oats in his youth, and, after having had the full run of himself in ill-natured transactions, might have turned out amiable, at last, for the sake of a little freshness and novelty. But, cramped and chafing in the peaceable pursuit of toy-making, he was a domestic Ogre, who had been living on children all his life, and was their implacable enemy. He despised all toys; wouldn't have bought one for the world; delighted, in his malice, to insinuate grim expressions into the faces of brown-paper farmers who drove pigs to market, bellmen who advertised lost lawyers' consciences, movable old ladies who darned stockings or carved pies; and other like samples of his stock in trade. In appalling masks; hideous, hairy, red-eyed Jacks in Boxes; Vampire Kites; demoniacal Tumblers who wouldn't lie down, and were perpetually flying forward, to stare infants out of countenance; his soul perfectly revelled. They were his only relief, and safety-valve. He was great in such inventions. Anything suggestive of a Pony-nightmare was delicious to him. He had even lost money (and he took to that toy very kindly) by getting up Goblin slides for magic-lanterns, whereon the Powers of Darkness were depicted as a sort of supernatural shell-fish, with human faces. In intensifying the portraiture of Giants, he had sunk quite a little capital; and, though no painter himself, he could indicate, for the instruction of his artists, with a piece of chalk, a certain furtive leer for the countenances of those monsters, which was safe to destroy the peace of mind of any young gentleman between the ages of six and eleven, for the whole Christmas or Midsummer Vacation. ["Chirp the First," 177]

In the scene with John after he has revealed to the doting middle-aged husband what looks like adultery, Tackleton momentarily assumes the role of Shakespeare's Iago, the jealous, satanic tempter, to John's Othello, as he pushes John towards violence against the youth who seems to have captured Dot's heart. John's capacity for both self-blame and forgiveness thwarts Tackleton's evil designs. Appropriately, Leech depicts him well in the background of the final illustration, dancing with the elderly Mrs. Fielding, perhaps to underscore the unsuitability of his putative match with May. However, both Household illustrators, E. A. Abbey and Fred Barnard, have taken a greater degree of interest in the enigmatic would-be villain of the piece; whereas Barnard treats Tackleton with detached humour in the scene in which Bertha extols him as a kind and caring employer, Abbey interprets him as a slender, fashionably-dressed gentleman who serves in his malice as John's alter ego. Despite the fact that the powerful carrier is gripping him by the throat, Abbey's Tackleton, a calculating strategist, is unperturbed.

In Furniss's illustration, however, the egotistical Tackleton is merely an elegant if puffed up exterior who represents no real threat to the happiness of the characters to the left: Edward and May (left of centre), confronting him; Caleb and Bertha (seated), looking on; and John and Dot (standing in front of the window), wrapped up in each other and oblivious to Tackleton's dialogue with Edward. His dramatic entrance is emphasized by his cloak pulled aside, his rakish top hat, his right leg extended well forward (suggestive of an agressive state of mind), and the chiaroscuro of his ample figure created by the open door of John's cottage behind him. The gesture he makes with his left hand admirably expresses his complete contempt for the institution of marriage in general, and the marriage of Edward Plummer and May Fielding in particular. In contrast to the genuine threat that Abbey's Tackleton poses the others, this Tackleton is a pasteboard villain at best.

Related Materials and Details

- The Christmas Books of Charles Dickens

- Felix O. C. Darley's character study "Father," said the Blind Girl, drawing close to his side (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s single illustration for The Cricket on the Hearth (1867)

- Felix O. C. Darley's character study Bertha, the Blind Girl, May Fielding, and Caleb Plummer (1888)

- A. E. Abbey's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1876)

- Fred Barnard's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1878)

Related Illustrations in Earlier Editions

Left: Detail from John Leech's The Dance; centre, Fred Barnard's After dinner, Caleb sang the song about the Sparkling Bowl(1878); right: detail from Barnard's view of Tackleton in the Plummers' worksho

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bolton, H. Phili "The Cricket on the Hearth." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987, 273-95.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. , 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844 [dated 1845].

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910, VIII, 79-157.

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

__________. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 4, "The Chord of the Christmas Season." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982, 62-93.

Created 4 July 2013

Last modified 3 January 2020