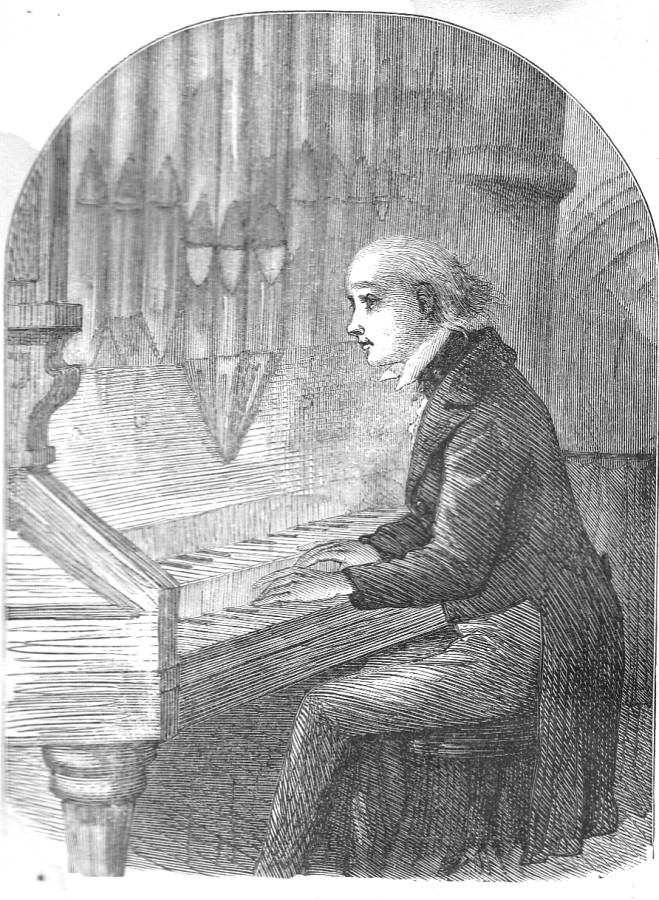

"Touch the notes lightly, Tom" (1910). Twenty-ninth and final lithograph by Harry Furniss for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Chapter LIV), facing page 856. [This is not entirely a melancholy composition since includes the disreputable Pecksniff as well as an idealized image of Mary Graham, but it constitutes a reinterpretation of Phiz's final illustration sixty-six years earlier.] 14 x 9.2 cm, vignetted (5 ½ high by 3 ⅝ inches). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Apostrophe to Tom Pinch

What sounds are these that fall so grandly on the ear! What darkening room is this!

And that mild figure seated at an organ, who is he! Ah, Tom, dear Tom, old friend!

Thy head is prematurely grey, though Time has passed thee and our old association, Tom. But, in those sounds with which it is thy wont to bear the twilight company, the music of thy heart speaks out: the story of thy life relates itself.

Thy life is tranquil, calm, and happy, Tom. In the soft strain which ever and again comes stealing back upon the ear, the memory of thine old love may find a voice perhaps; but it is a pleasant, softened, whispering memory, like that in which we sometimes hold the dead, and does not pain or grieve thee, God be thanked.

Touch the notes lightly, Tom, as lightly as thou wilt, but never will thine hand fall half so lightly on that Instrument as on the head of thine old tyrant brought down very, very low; and never will it make as hollow a response to any touch of thine, as he does always. [Chapter LIV, "Gives the Author great Concern. For it is the Last in the Book," 862: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary: Melancholy Tom, Perpetual Bachelor

Right: Detail of Furniss's inset portrait of the dissolute Pecksniff, The Begging-Letter Writer.

"I have a notion of finishing the book, with an apostrophe to Tom Pinch, playing the organ." — "Dickens to Phiz," June 1844.

The 1910 Furniss illustration of Tom Pinch at the organ, the book's last, is his re-interpretation of a similar illustration in the final monthly number of the Chapman and Hall serialisation, Hablot Knight Browne's Frontispiece (see below) for Chapter 54 (Parts Nineteen-Twenty, July 1844 ). However, governing his much more complex composition according to the principles of Nemesis, Phiz focusses on Tom as the vortex's centre, surrounded by the other characters in the story. Furniss's approach is much closer to that of Fred Barnard in Tom's Reverie (see below). In Furniss more light-hearted interpretation we have a rejection of Barnard's vision of Tom as a social isolate in perpetual darkness. Much more so than in Phiz’s original frontispiece, Barnard excludes Tom from the happy ending typical of the Victorian Novel, as governed by Poetic Justice. Thus, Barnard keeps Tom in the darkness of bachelorhood, outside “the magic circle” of the Victorian novel’s typical happy ending: romance, marriage, children, health, and material prosperity that the virtuous protagonist such as Martin receives as a consequence of his having striven always to do the right thing, or at least having learned the virtue of caring more about others than one’s self.

For Dickens and Phiz, despite the fact that Tom's organ-playing has been purely incidental to the plot and his character up to this point, the central image of the frontispiece — one of the last illustrations executed but one of the first the reader of the volume edition would have seen on 16 July 1844, the central image, Tom at a church organ (indeed, all three chief interpretations concur on this setting), represents the inspired artist's contemplating his work, life, and relationships; it eventually will blend into illustrator R. W. Buss's memorial to Charles Dickens as a highly prolific author, Dickens' Dream which makes explicit the connection between the legion of characters that flowed from his pen and the man himself. The frontispiece brings closure to the story by supplying information as images rather than letterpress about the characters after the close of the novel, showing us, for example, that Mark Tapley marries the Blue Dragon and its proprietor, Mrs. Lupin (left of centre) in one of the many joyful "dance of life" scenes that crowd the left-hand margin (the right of the original steel engraving). Thus, the frontispiece continues the wrapper's program of contrasting figures and fortunes, but as a preview is rather more specific about the fates of the various characters.

The Furniss approach is less fanciful, but retains a certain sense of whimsy in its depiction of a suffering, self-pitying, disreputable Pecksniff (now an unkempt alcoholic) and of the contrasting, aetherial presence of Mary Graham, hovering above Tom's shoulder as his idealised woman and poetic muse. Furniss, moreover, offers a joyful and satisfied Tom, smiling in a benign manner, and seemingly prosperous and fulfilled, in stark contrast to the disreputable dwarf hunched up on the floor, right. Mary Graham, of course, has become Martin Chuzzlewit's wife and the object of Tom's unrequited devotion. Sadly, like Antonio at the conclusion of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, Tom remains outside the enchanted marriage circle as he contemplates both what has been and what might have been. Furniss emphasizes Tom's bald pate, not merely to underscore his being middle-aged but single, but to endow him with a cerebral, philosophical disposition as in the accompanying text. Since the illustration occurs some five pages prior to the passage which Hammerton suggests through its title that it realizes, we read the composition proleptically, anticipating that the image means Tom never marries, and finds true fulfilment only in his art.

Whereas Ticknor-Fields mid-nineteenth-century American illustrator for the 1867 Diamond Edition, Sol Eytinge, Jr., has depicted Tom as an organ soloist in a series of illustrations in which the other characters consistently appear in groups or pairs, Fred Barnard in the 1872 Household Edition wood-engraving Tom's Reverie (see immediately below) places the emphasis on Tom's leaving behind his sister and brother-in-law (shadowy figures in the background) and entering another sphere as his hands assume very specific places on the twin keyboards. In other words, we might view Furniss's interpretation as an imaginative response to Barnard's atmospheric but realistic dark plate and Phiz's more fanciful invention.

Related Materials: Background, Setting, and Characterization

- The Anti-Technological Bias of

Victorian Education and Britain's Economic Decline

- Dickens's 1842 Reading Tour: Launching the Copyright Question in Tempestuous Seas

- Dickens's Impressions of the Mississippi valley at Cairo, Illinois, the original of "Eden" in Martin Chuzzlewit

- A Bad Trip: The Trouble with Martin Chuzzlewit

- From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphery's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit [chapter from Steig's Dickens and Phiz

- The critics and the characters in Martin Chuzzlewit

- The Names of Dickens's American Originals in Martin Chuzzlewit

- Seth Pecksniff, Architect

- The Divine Sairey Gamp: An Enduring Comic Masterpiece

- "Jolly" Mark Tapley in Martin Chuzzlewit — one of Dickens's most popular originals

- Dickens's Jonas in Martin Chuzzlewit and Milton's Satan

- Tom Pinch's love of bookstores

- Dickens's 1842 Reading Tour: Launching the Copyright Question in Tempestuous Seas

Other Programs of Illustration, 1843-1923

- Illustrations by Which to Read Martin Chuzzlewit: The Phiz Steels (1843-44) or the Barnard Woodcuts (1872)

- Illustrations by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

- Illustrations by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Illustrations by Fred Barnard (1872)

- Illustrations by Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1863)

- Illustrations by Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke) (1910)

- Illustrations by Harold Copping (1923)

Relevant Illustrations, 1843-1872

Left: Phiz's Frontispiece (July 1844), a perfect riot of poetic invention. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Phiz-inspired but much more realistic frontispiece for the Diamond Edition, Tom Pinch (1867), in which the artist is quite alone with his art. Right: Phiz's Chapter 54 illustration that dwells instead upon Charity Pecksniff's being jilted by Mr. Moddle, The Nuptials of Miss Pecksniff receive a temporary check (July 1844 number, which covers Chapters 51 through 54).

Above: Barnard's concluding illustration in the long sequence, Tom's Reverie (1872).

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Barnard, Fred, and M. Walton. Ten Characters from Dickens. Ten original pen & ink drawings, after Barnard: Dombey & Son; The Two Wellers; Mr. Pecksniff; Sydney Carton; Alfred Jingle; Mark Tapley & Tom Pinch; Mr. Peggotty; Mrs. Gamp; Rogue Riderhood; Mr. Pickwick. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1879.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vols. 1 to 4.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Guerard, Albert J. "Martin Chuzzlewit: The Novel as Comic Entertainment." The Triumph of the Novel: Dickens, Dostoevsky, Faulkner. Chicago & London: U. Chicago P., 1976, 235-60.

Hammerton, J. A. Ch. 15, "Martin Chuzzlewit." The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the Dickens Illustrations with 600 Illustrations and a Frontispiece by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vois. London: Educational Book, 1910. XVII, 266-93.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Martin Chuzzlewit — Fifty-nine Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Steig, Michael. "III. From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978, 51-85.

_____. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-49.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Created 18 January 2016

Last modified 28 November 2024