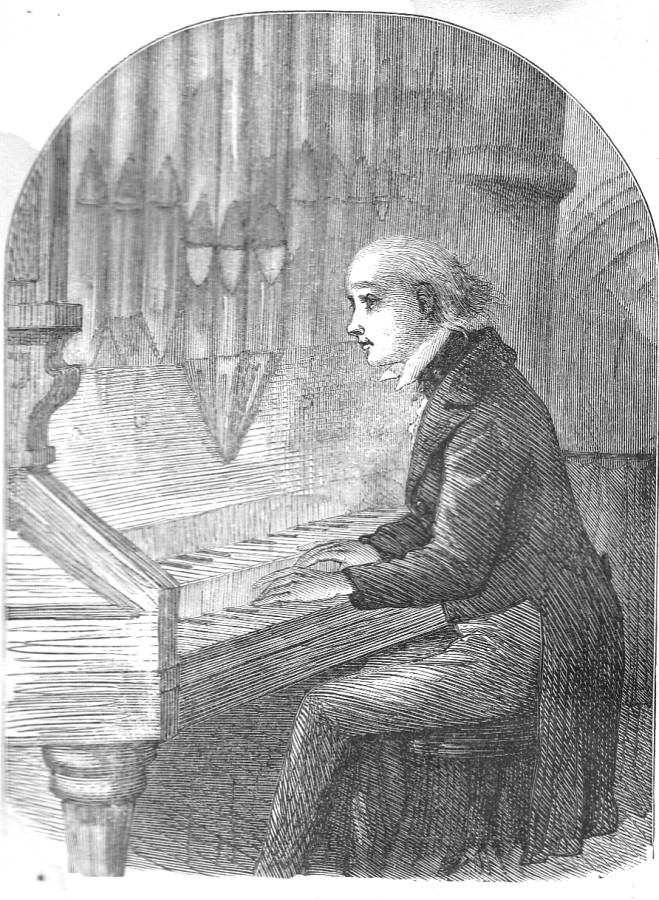

Tom Pinch

Sol Eytinge

Wood engraving, approximately 10 cm high by 7.5 cm wide (framed), facing title-page

Initial illustration for Dickens's The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit in the Ticknor and Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition.

In this first full-page character study for the novel, Eytinge examines the transported creative artist, the good-hearted but naive Tom Pinch, the friend of both John Westlock and Martin Chuzzlewit who, unlike these other eirons, does not marry at the conclusion of the story, but plays the organ in solitary reverie at the conclusion of the novel and the winding up of all the other threads of the picaresque plot. [Continued below]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Whereas Eytinge usually "pairs" characters for his studies, significantly he here opens the narrative-pictorial sequence with a solitary Tom engaged in a toccata fantasy at the organ, realising an "apostrophe" from the very final page of the novel. In the manner of John Keats in"Ode on a Grecian Urn" (text of poem), Dickens introduces his final portrait of Tom Pinch by rhetorically questioning the source of the melancholy music and apostrophising Tom in the formal, archaic second-person favoured by the romantic poets:

What sounds are these that fall so grandly on the ear! What darkening room is this!

And that mild figure seated at an organ, who is he! Ah Tom, dear Tom, old friend!

Thy head is prematurely grey, though Time has passed thee and our old association, Tom. But, in those sounds with which it is thy wont to bear the twilight company, the music of thy heart speaks out, — the story of thy life relates itself.

Thy life is tranquil, calm, and happy, Tom. In the soft strain which ever and again comes stealing back upon the ear, the memory of thine old love may find a voice perhaps; but it is a pleasant, softened, whispering memory, like that in which we sometimes hold the dead, and does not pain or grieve thee, God be thanked.

Touch the notes lightly, Tom, as lightly as thou wilt, but never will thine hand fall half so lightly on that Instrument as on the head of thine old tyrant brought down very, very low; and never will it make as hollow a response to any touch of thine, as he does always.

For a drunken, begging, squalid, letter-writing man, called Pecksniff, with a shrewish daughter, haunts thee, Tom; and when he makes appeals to thee for cash, reminds thee that he built thy fortunes better than his own; and when he spends it, entertains the alehouse company with tales of thine ingratitude and his munificence towards thee once upon a time; and then he shows his elbows worn in holes, and puts his soleless shoes up on a bench, and begs his auditors look there, while thou art comfortably housed and clothed. All known to thee, and yet all borne with, Tom!

So, with a smile upon thy face, thou passest gently to another measure, — to a quicker and more joyful one, — and little feet are used to dance about thee at the sound, and bright young eyes to glance up into thine. And there is one slight creature, Tom, — her child; not Ruth's, — whom thine eyes follow in the romp and dance; who, wondering sometimes to see thee look so thoughtful, runs to climb up on thy knee, and put her cheek to thine; who loves thee, Tom, above the rest, if that can be; and falling sick once, chose thee for her nurse, and never knew impatience, Tom, when thou wert by her side.

Thou glidest, now, into a graver air; an air devoted to old friends and bygone times; and in thy lingering touch upon the keys, and the rich swelling of the mellow harmony, they rise before thee. The spirit of that old man dead, who delighted to anticipate thy wants, and never ceased to honour thee, is there, among the rest; repeating, with a face composed and calm, the words he said to thee upon his bed, and blessing thee! [Ch. 54, The Diamond Edition, p. 480]

Dickens wrote to Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz") in June 1844, "I have a notion of finishing the book, with an apostrophe to Tom Pinch, playing the organ" (Pilgrim Letters 3: 140). As Valerie Lester Browne points out in Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004), the images embedded in the original frontispiece (and anticipating R. W. Buss's "Dickens Dream") suggest what will befall the various characters several years after the story's textual conclusion, as well as (to a lesser extent) their experiences and roles during the course of the narrative. Consequently, like many a modern preface, the original frontispiece, "Tom Pinch at the Organ", and Eytinge's scaled-down version (undoubtedly the medium of the woodcut did not permit the elaboration which Phiz was earlier able to effect in his 1844 steel engraving) are both better understood once the reader has completed the novel. However, Eytinge may have been targeting those mature readers who in 1867 would have recalled the novel as part of their youthful reading, and who would, therefore, have understood the significance of this musical portrait of the novel's "odd man out" in terms of the ultimate magic circle of romance. Sadly, unlike Phiz's, Eytinge's image fails to convey the prematurely balding Tom's sterling qualities or the fates of the various characters, and thereby regards merely Tom's exterior rather than his intense imaginative and emotional life.

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. "The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1842-43). Il. Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. "Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Bros.; Londonb: Chapman and Hall, 1872.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Martin

Chuzzlewit

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 30 April 2012