Sairey Gamp by Harry Furniss in The Charles Dickens Library Edition, (1910) — from Chapter 22, "From Which It Will Be Seen that Martin Became a Lion on His Own Account. Together with the Reason Why." Here is the quintessential Sairey Gamp as created by Hablot Knight Browne from a Daumier cartoon, and elaborated by seventies illustrator Fred Barnard in The Household Edition. The Furniss images, necessarily derivative, reveal a certain benign quality in the visage not present in the Phiz and Barnard interpretations. One of Dickens's most brilliant comic creations, she occupies a place of prominence in the ornamental border for Furniss's title-page, Characters in the Story (bottom left-hand corner). The portrait (12.1 x 8.5 cm, vignetted) occupies its own page, facing VII, 385.

Passage Illustrated

Mrs. Gamp had a large bundle with her, a pair of pattens, and a species of gig umbrella; the latter article in colour like a faded leaf, except where a circular patch of a lively blue had been dexterously let in at the to She was much flurried by the haste she had made, and laboured under the most erroneous views of cabriolets, which she appeared to confound with mail-coaches or stage-wagons, inasmuch as she was constantly endeavouring for the first half mile to force her luggage through the little front window, and clamouring to the driver to 'put it in the boot.' When she was disabused of this idea, her whole being resolved itself into an absorbing anxiety about her pattens, with which she played innumerable games at quoits on Mr Pecksniff's legs. It was not until they were close upon the house of mourning that she had enough composure to observe —

"And so the gentleman's dead, sir! Ah! The more's the pity." She didn't even know his name. "But it's what we must all come to. It's as certain as being born, except that we can't make our calculations as exact. Ah! Poor dear!"

She was a fat old woman, this Mrs. Gamp, with a husky voice and a moist eye, which she had a remarkable power of turning up, and only showing the white of it. Having very little neck, it cost her some trouble to look over herself, if one may say so, at those to whom she talked. She wore a very rusty black gown, rather the worse for snuff, and a shawl and bonnet to correspond. In these dilapidated articles of dress she had, on principle, arrayed herself, time out of mind, on such occasions as the present; for this at once expressed a decent amount of veneration for the deceased, and invited the next of kin to present her with a fresher suit of weeds; an appeal so frequently successful, that the very fetch and ghost of Mrs. Gamp, bonnet and all, might be seen hanging up, any hour in the day, in at least a dozen of the second-hand clothes shops about Holborn. The face of Mrs Gamp — the nose in particular — was somewhat red and swollen, and it was difficult to enjoy her society without becoming conscious of a smell of spirits. Like most persons who have attained to great eminence in their profession, she took to hers very kindly; insomuch that, setting aside her natural predilections as a woman, she went to a lying-in or a laying-out with equal zest and relish. [Chapter 19, "The Reader is Brought into Communication with Some Professional Persons, and Sheds a Tear over the Filial Piety of Good Mr. Jonas," 325-26]

Commentary: The Inimitable Sairey Gamp

Over the course of a number of illustrated editions of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) a number of versions of the novel's bibulous sick-room nurse, Mrs. Gamp (whose name derives from her omnipresent umbrella) appeared, by Hablot Knight Browne, Felix Octavius Carr Darley, Sol Eytinge, Jr., the lead Household Edition illustrator, Barnard, and Furniss. However, all of these are based on the original conception by Phiz, to which Clayton J. Clarke paid tribute in his series of Dickens illustrations for Players' Cigarette cards in 1910. Furniss's interpretation is slightly more animated and less cartoonish than the Phiz original, which in turn was based on Honoré Daumier's Sick-room Nurse ("La Garde-Malade") in the Paris magazine Le Charivari, 22 May 1842, made her an overnight Victorian icon. Barnard, working with both Dickens's text and Phiz's highly popular visualisation, had to synthesize everything he knew about Mrs. Gamp, including her appearances later in the novel and some four decades of her popular reception, a synthesis upon which such later illustrators as Kyd and Furniss based their interpretations.

Perhaps nowhere else in Phiz's narrative-pictorial sequence for the initial serialisation of Martin Chuzzlewit is the illustrator's imagination so stimulated by the letterpress, with the result that Phiz describes not merely the outward and visible signs of the two sick-room nurses in Mrs. Gamp Propoges a Toast (June 1844), but also captures their milieu and ultimately the essence of the immortal Sairey herself. Every detail from Dickens's letterpress is present, and is depicted in proper relation to every other object, right down to the central object not merely of the room but of Sairey's inner life, the convivial teapot, the sacred chalice under whose influence Sairey's alcohol-tinged syllables take flight into the aether of world literature. She is here, like her visual and verbal creators, a great inimitable, doubled by the dresses that like angelic facsimile Saireys hover above their original. Whereas Fred Barnard incorporates all of these elements into his 1879 portrait of the inimitable Sairey for Character Sketches from Dickens, Harry Furniss, like Kyd and Eytinge, focuses on her person and does not supply contextual details. That she is sitting down rather than standing and is holding a small glass points to the passage in which Mr. Mould, the undertaker, offers her some rum punch in Chapter 25.

Although Dickens introduces his readers to one of his greatest comic creations, Mrs. Gamp, in the eighth instalment of the novel, illustrator Barnard in his 1879 character sketch seems to be thinking of the divine Sairey as she appears in Chapter 25 because his caption, Mrs. Gamp on the Art of Nursing, is thematically connected with that chapter's title: "Is in part professional; and furnishes the reader with some valuable hints in relation to the management of a sick chamber." So effective was Barnard's character study that Dana Estes, Boston, used it as the frontispiece for its fin-de-siecle edition of the novel: "Etched by S. A. Schoff — From a Drawing by Frederick Barnard" (12 cm high by 10 cm wide).

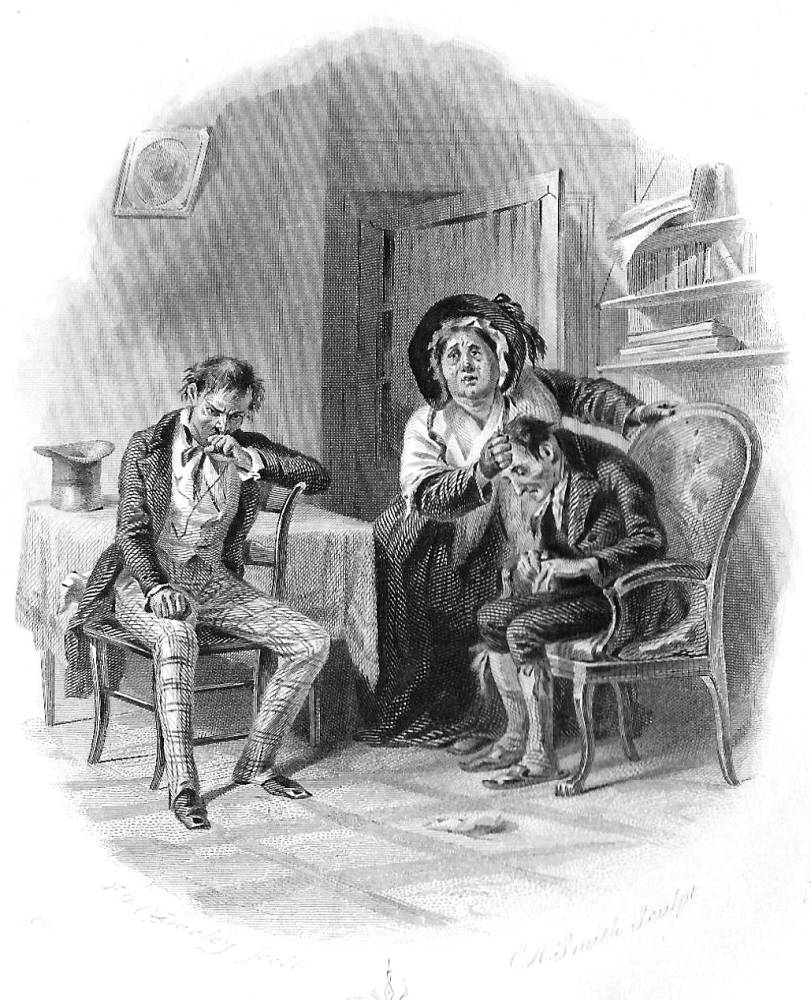

Dickens introduces Mrs. Gamp comparatively late in the serial, in the Chapter 19 passage (above) that Eytinge obviously had to assimilate in rendering the scene at the Bull Tavern later on. Although we do not actually see much of her as she leans out of the window above Poll Sweedlepipe's shop in Phiz's Chapter 19 illustration Mr. Pecksniff on his Mission (August 1843), this is nevertheless her entry point not only in a minor novel but also into nineteenth-century popular culture. Phiz provides three scenes depicting the boozey face and voluminous figure of the alcoholic midwife Mrs. Gamp, Dickens's satire on private nurses, and her faithful confederate, Betsey Prig. On the other hand, Barnard's six 1872 Household Edition woodcuts involving this comic figure depict Sairey with greater frequency and detail, so iconic a figure of English comedy had she become over thirty years separating the two editions. In America, she appears just once in the Darley Household Edition frontispieces, and just once in Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s wood-engravings for the Diamond Edition. Felix Octavius Carr Darley's "The creetur's head's so hot," said Mrs. Gamp (see below), a photogravure for volume four of the 1863 "Household" Edition, is much sharper than Eytinge's plate, but not nearly as amusing because Darley draws her realistically, without comic distortion. Furniss, who recognized her enduring legacy as one of Dickens's great comic creations, has her appear four times in twenty-nine illustrations, whereas the eponymous hero appears only seven times in the 1910 sequence. Out of the novel's seventy-three named characters, the three most memorable are Mark Tapley, Seth Pecksniff, and Mrs. Gamp, all three secondary figures being essentially comic creations.

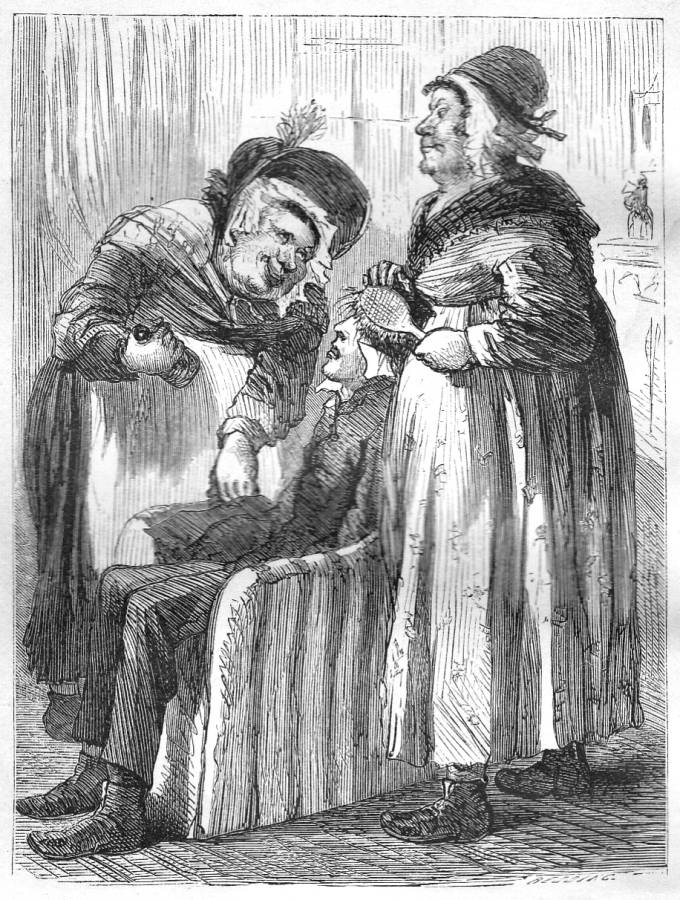

While Barnard felt compelled to make his figures of Mrs. Gamp and Betsey Prig conform to those of the original 1843-44 serial, Eytinge has departed somewhat from that androgynous image, although he has retained her enormous hat, full face, and alcoholic nose, all of which serve to distinguish Mrs. Gamp (left) from Betsey, wielding the hairbrush ruthlessly as she holds fast to the patient's head (right). In Eytinge's woodcut, Sairey has just discovered the "night-bottle" of gin that she had placed in the delirious Lewsome's coat-pocket. One receives a clear image of the two women, but not much insight into their relationship — and Eytinge seems not much interested in the patient, who ultimately reveals a key plot secret. The classic image of Mrs. Gamp, taking a little something against the cold, remains Barnard's 1872 frontispiece Mrs. Gamp, on the Art of Nursing, in which she contemplates her gigantic bonnet; Barnard has included her umbrella (from which she takes the surname "Gamp") and the proverbial bottle on the chimbley-piece, ready to hand. Here we see the direct origins of the Furniss illustrations of Mrs. Gam

Although originally intended to be just a bit part, like a ham actor, a mere butt of Dickens's satire of drunken, disreputable nurses, Sairey consistently upstages the story's principals whenever she appears. Although she does not exactly "develop" as a character, she certainly blossoms. Although he has, according to the caption, seated her in the undertaker Mr. Mould's parlour, Barnard has in fact situated her in her comfortable "chimley" corner. The illustrator crams into the study almost every visual detail associated with the bleery-eyed, husky-voiced, androgynous figure of capacious dimensions: the short, thick neck; the round face; the swollen nose (so forcibly anticipating that of W. C. Fields as the quintessence of the inveterate tippler); rusty black gown stained by snuff; oversize bonnet; bottle stationed on the mantelpiece; and, of course, her conspicuous umbrella or "gamp" from which she derives her surname. Instead of showing her turning her eyes upward, as is her wont, Barnard has her thoughtfully gazing at the viewer, as if he or she is about to become the next client.

Although superfluous to the extended Chuzzlewit family, Mrs. Gamp as a sick-room nurse connects the main elements of the plot surrounding the death of Anthony Chuzzlewit as she attends the elderly, infirm clerk Chuffey while Jonas is in the country, looks after Lewsome at the Bull Inn, and has a role in John Westlock's exposure of Jonas in Chapter 51.

Related Materials: Background, Setting, Characterization

- Dickens's 1842 Reading Tour:

Launching the Copyright Question in Tempestuous Seas

- Dickens's Impressions of the Mississippi valley at Cairo, Illinois, the original of "Eden" in Martin Chuzzlewit

- A Bad Trip: The Trouble with Martin Chuzzlewit

- From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphery's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit [chapter from Steig's Dickens and Phiz

- The critics and the characters in Martin Chuzzlewit

- The Names of Dickens's American Originals in Martin Chuzzlewit

- Seth Pecksniff, Architect

- The Divine Sairey Gamp: An Enduring Comic Masterpiece

- "Jolly" Mark Tapley in Martin Chuzzlewit — one of Dickens's most popular originals

- Dickens's Jonas in Martin Chuzzlewit and Milton's Satan

- Tom Pinch's love of bookstores

Other Programs of Illustration, 1843-1923

- Illustrations by Which to Read Martin Chuzzlewit: The Phiz Steels (1843-44) or the Barnard Woodcuts (1872)

- Illustrations by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

- Illustrations by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Illustrations by Fred Barnard (1872)

- Illustrations by Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1863)

- Illustrations by Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke) (1910)

- Illustrations by Harold Copping (1923)

Relevant Sairey Gamp illustrations, 1843 to 1910

Left: Phiz's Mrs. Gamp Propoges a Toast (Ch. 49, June 1844). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Sairey Gamp and Betsey Prig. .

Left: Darley's frontispiece for volume two, "The creetur's head's so hot," said Mrs. Gamp, alluding to her attendance on the old clerk, Chuffey. Centre: Kyd's miniature portrait of Mrs. Gamp walking through the streets with hat, bag, and umbrella, Sairey Gamp (card no. 24, 1910). Right: From Kyd's book of remarkable Dickens characters, Sairey Gamp in watercolour, as seen in Ch. 19.

Above: Barnard's Mrs. Gamp favours the company with an exhibition of professional skill, old Chuffey being the object of her ministrations (Chapter 46, the Household Edition, 1872).

Above: Barnard's Sairey Gamp rose — morally and physically rose — and denounced her (Chapter 49, the Household Edition, 1872).

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. , 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

__________. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

__________. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

__________. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vols. 1 to 4.

__________. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

__________. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Guerard, Albert J. "Martin Chuzzlewit: The Novel as Comic Entertainment." The Triumph of the Novel: Dickens, Dostoevsky, Faulkner. Chicago & London: U. Chicago , 1976, 235-60.

Hammerton, J. A. Ch. 15, "Martin Chuzzlewit." The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the Dickens Illustrations with 600 Illustrations and a Frontispiece by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vois. London: Educational Book, 1910. XVII, 266-93.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Martin Chuzzlewit — Fifty-nine Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Steig, Michael. "III. From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. , 1978, 51-85.

__________. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-49.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Created 25 November 2015

Last modified 15 January 2020