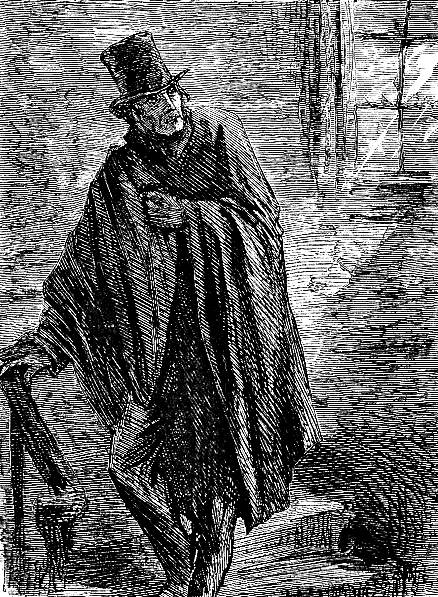

Monks

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist

Edward Leeford, acting under his criminal alias "Monks," appears by himself rather than, as in James Mahoney's Household Edition sequence, with Fagin, his confederate in his scheme to defraud Oliver. A shadowy figure out of Gothic fiction and the demonic species of early nineteenth-century melodrama, Monks wears a cloak rather than a topcoat; however, his silk hat is a class-marker, for he is a gentleman gone bad.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Passage Illustrated

"Come in!" he cried impatiently, stamping his foot upon the ground. "Don't keep me here!"

The woman, who had hesitated at first, walked boldly in, without any other invitation. Mr. Bumble, who was ashamed or afraid to lag behind, followed: obviously very ill at ease and with scarcely any of that remarkable dignity which was usually his chief characteristic.

"What the devil made you stand lingering there, in the wet?" said Monks, turning round, and addressing Bumble, after he had bolted the door behind them. "We — we were only cooling ourselves," stammered Bumble, looking apprehensively about him.

"Cooling yourselves!" retorted Monks. "Not all the rain that ever fell, or ever will fall, will put as much of hell's fire out, as a man can carry about with him. You won't cool yourselves so easily; don't think it!"

With this agreeable speech, Monks turned short upon the matron, and bent his gaze upon her, till even she, who was not easily cowed, was fain to withdraw her eyes, and turn them towards the ground.

"This is the woman, is it?" demanded Monks.

"Hem! That is the woman," replied Mr. Bumble, mindful of his wife's caution.

"You think women never can keep secrets, I suppose?" said the matron, interposing, and returning, as she spoke, the searching look of Monks.

"I know they will always keep one till it's found out," said Monks.

"And what may that be?" asked the matron.

"The loss of their own good name," replied Monks. "So, by the same rule, if a woman's a party to a secret that might hang or transport her, I'm not afraid of her telling it to anybody; not I! Do you understand, mistress?"

"No," rejoined the matron, slightly colouring as she spoke.

"Of course you don't!" said Monks. "How should you?"

Bestowing something half-way between a smile and a frown upon his two companions, and again beckoning them to follow him, the man hastened across the apartment, which was of considerable extent, but low in the roof. He was preparing to ascend a steep staircase, or rather ladder, leading to another floor of warehouses above: when a bright flash of lightning streamed down the aperture, and a peal of thunder followed, which shook the crazy building to its centre.

"Hear it!" he cried, shrinking back. "Hear it! Rolling and crashing on as if it echoed through a thousand caverns where the devils were hiding from it. I hate the sound!" He remained silent for a few moments; and then, removing his hands suddenly from his face, showed, to the unspeakable discomposure of Mr. Bumble, that it was much distorted, and discoloured.

"These fits come over me, now and then," said Monks, observing his alarm; "and thunder sometimes brings them on. Don't mind me now; it's all over for this once."

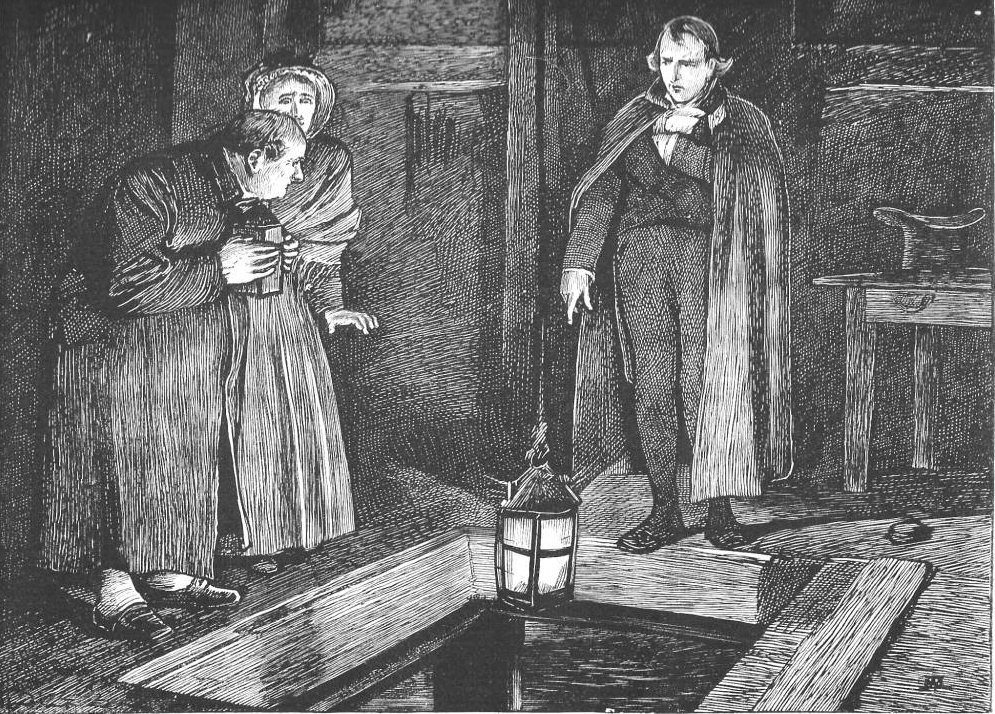

Thus speaking, he led the way up the ladder; and hastily closing the window-shutter of the room into which it led, lowered a lantern which hung at the end of a rope and pulley passed through one of the heavy beams in the ceiling: and which cast a dim tight upon an old table and three chairs that were placed beneath it. [Chapter 38, "Containing an account of what passed between Mr. and Mrs. Bumble, and Mr. Monks, at their nocturnal interview," p. 162]

Commentary: Maintaining Monks's Air of Mystery

The picture derives considerable meaning from its context, the chapter in which Monks destroys the evidence of the marriage of Oliver's mother, evidence that he has just acquired from the Bumbles. The arrival of the shadowy figure of "Monks," the alias of Edward Leeford, Oliver's half-brother, transforms the narrative from a Newgate Novel and a possible bildungsroman into a mystery. Now the narrative begins to reveal Fagin's true motives in training the boy to become a thief, for Oliver will either vanish from middle-class eyes into the murky criminal underworld of London, or be incarcerated, or transported — or executed as a felon, and therefore never realise that he is the legitimate heir of Edwin Leeford. This shadowy figure of the evil, plotting step-brother who covets Oliver's portion of the patrimony — a Cain to Oliver's Abel — is the subject of Sol Eytinge, Junior's character study Monks in the 1867 Diamond Edition of the novel. As is consistent with the accompanying text, Eytinge shows the "steep staircase" (about which Dickens corrects himself in order to specify instead a "ladder") and shattered window of the abandoned factory (the industrial age equivalent of the ruinous mediaeval castle of Gothic fiction and melodrama), but not the pathetic fallacy of thunder and lightning against which the scene plays out, or Monks's lantern, the heavy beams, the pulley, the chairs, or — significantly — the chute down to the river.

Whereas most Eytinge studies in this edition are of a pair of associated characters, such as Bill Sikes and Nancy, here the American illustrator, well aware chapters earlier than was George Cruikshank of Monks's importance to the inheritance plot, shows the egocentric, malevolent villain by himself, alienated, and brooding, the moody child of privilege who considers nobody's welfare but his own. As Juliet John stipulates, Monks puts his own wounded feelings, exacerbated by a jealous and vindictive mother, "before law, family, or community" (51). The cape in which the various illustrators clothe him is the outward and visible sign of his attempt to act in secret, so that he works with his underworld associates under an assumed identity and under cover of darkness. His manner and speech, however, betray his true background. His association with Fagin in Cruikshank's June 1838 illustration Monks and the Jew shows that he is prepared to violate the barriers of class and propriety in order to advance his fortunes, even at the cost of Oliver's life. Eytinge, like Cruikshank, depicts the venomous older brother as "a tall man wrapped in a cloak" (Ch. 34, p. 142), his height consistently exaggerated by his hat. In Eytinge's illustration, Monks acquires and destroys the evidence of Oliver's legitimacy, so that the reader believes erroneously that Monks will succeed in his plot with Fagin to have Oliver sucked into the criminal underworld, never again to be seen or heard of in middle-class society.

The August 1838 Cruikshank illustration The Evidence Destroyed is surely the basis for the later interpretations of Mahoney and Furniss, although Sol Eytinge has deviated with respect to setting from Cruikshank's precedent. While Eytinge's Monks lurks inside a building near a shattered window illuminated by lightning, on a darkened interior stair — an interpretation that accords well with the Gothic figure's clandestine and surreptitious nature, James Mahoney in the Household Edition volume's frontispiece has lowered and enlarged the lantern somewhat, thereby darkening the scene which in Eytinge's plate receives only the fitful illumination of the lightning storm without. Such Gothic associations are highly appropriate for a character whose name associates him with the anguished protagonist of Matthew G. Lewis 1795 Gothic potboiler The Monk.

Harry Furniss's much later rendering of the same scene heightens its drama by the artist's sharpened contrast of the black-and-white shading, the terror on the faces of the Bumbles, and the emphatic gesture of Monks, whose facial expression the viewer cannot discern. That Furniss gave the black-cloaked figure of Monks holding the lantern a place of prominence (the lower left-hand corner) in Characters in the Story suggests that the later artist felt this was a pivotal moment in the narrative, even if he felt it necessary to depict Monks with his signature hat on in both the vignette and the full-page lithograph, which we encounter immediately after Dickens's economical but telling description in the text.

With his moody, angry disposition, his inky cloak, his fits of epilepsy, and his inexplicable antipathy to Oliver, Monks is a fearful force combining features of antagonists from the early nineteenth-century monster and the demonic melodramas. His assumed name — that is, the pseudonym that he has chosen for himself, is the signifier of his being a social isolate, like the monk Ambrosio in Lewis's novel. The stage effects associated with the Gothic villain, lightning and trapdoors, make Monks a "sensational" character in the sense of "the violent emotional excitement of the literary fashion known as 'the romantic and the terrible'" (John, p. 51). Dramatists such as George Almar and C. Z. Barnett rightly recognized that bringing Monks on stage much earlier than in the novel would help the audience to make sense of the death of Oliver's middle-class mother in the workhouse, and moreover would prepare them for the resolution of the "lost heir" plot, even if Monks' alliance with the disreputable Fagin seems somewhat improbable. In his first appearance in the November 1838 Almar adaptation, in Act One, Scene One, Monks is overhearing conversations, cursing, and speaking in quasi-romantic verse; in other words, as compared with the naturalistic, street-flavoured speech of Fagin and Sikes, Monks speaks in the drawing-room language of an aristocratic villain in a contemporary melodrama:

The Gothic villain is invariably defined by expressive emotional excess; what distinguishes this excess from that of the 'good' characters in this excessive genre is that it does not respect social rules and boundaries. The Gothic villain puts personal feeling before law, family, or community and thus violates communal ethos. His disregard of the social world creates the impression of transcendence often associated with the 'real melodramatic' villain. Violent feeling is the hallmark of the Gothic villain and the intensity with which his feelings are expressed can create the impression that the villain is not human but super-human. [John, p. 51]

In his intelligence and cunning (as evidenced in his ability to appear and disappear at will in the murky world of Whitechapel governed by Fagin and Sikes) Monks seems to possess supernatural powers, and is governed not by a plausible love of money (which motivates Sikes, Crackit, and Fagin), but by a violent emotion which incapacitates him when he gives it free rein. Because Monks has his origins in theatre and the Gothic novels of Anne Radcliffe and Matthew G. "Monk" Lewis (from whence perhaps Dickens has derived his criminal alias) rather than realistic fiction, his passionate excesses are jarring in the novel, but acceptable in the nineteenth-century melodramatic adaptations of the novel. Monks' passion-freighted speeches towards the end of the novel are unconvincing because, as Juliet John points out:

they have no connection with the poetics of the novel or with any knowledge we have of a character who has remained stagily enigmatic throughout. These failures can be read as perfect instances of the novelist practising what he preaches — of taking literally the idea of the novel as theatre by making characters do the work that more fittingly belongs to the narrator. Alternatively, they can be seen as examples of characters attempting a kind of self-analysis which is ill at ease with the melodramatic mode of Dickens's early novels. [115]

Working on his illustrations for Oliver Twist in 1866-67, Sol Eytinge had considerable advantages over George Cruikshank in having read the entire novel in advance in volume form, and moreover in having (in all probability) seen one or more stage adaptations in Boston and New York (notably that Almar adaptation at New York City's Wintergarden Theatre in February 1860 in which Monks would have been present from the opening scene) that would have clarified for him both the melodramatic traditions embodied in the enigmatic figure of "Monks" and this character's importance in the novel's inheritance plot. He remains in the illustrations true to his Radcliffian origins, "foreign in flavour and atmosphere" (John, p. 50) as we see here in Eytinge's portrait of a diabolical, enigmatic figure who instantly arouses fear in the beholder.

Illustrations from the initial serial edition (1837-39), Household Edition (1871), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: George Cruikshank's The Evidence Destroyed. Right: James Mahoney's The Evidence Destroyed (Frontispiece). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Harry Furniss's "Monks and Fagin watching Oliver asleep" (1910). Right: Harry Furniss's "The Evidence destroyed" (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davies, Philip. "Warren of Sunless Courts." Lost London, 1870-1945. Croxley Green, Hertfordshire: Transatlantic, 2009. Pp. 258- 260.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. The Annotated Dickens. Ed. Edward Guiliano and Philip Collins. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1. Pp. 534-823.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 3.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

John, Juliet. "Villains of Stage Melodrama: Romanticism and the Politics of Character. "Dickens's Villains: Melodrama, Character, Popular Culture. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2001 (rpt 2003). Pp. 42-69.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Oliver

Twist

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 1 March 2016