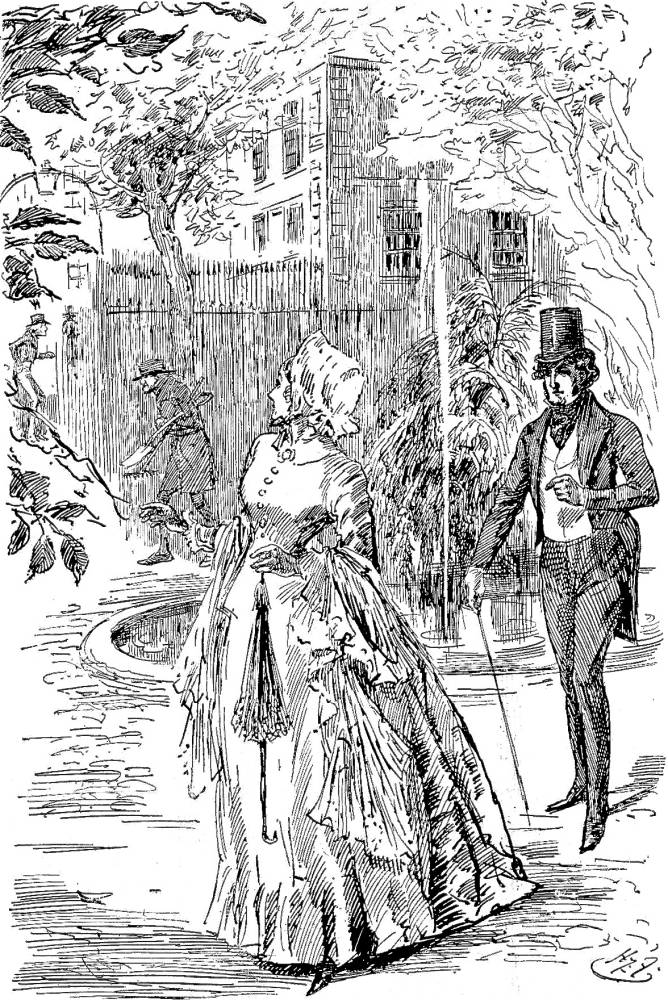

John Westlock and Ruth Pinch

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

wood-engraving

10 cm high by 7.5 cm wide (framed)

Poetic justice controls the final actions of the novel, as Old Martin denounces Pecksniff and is reconciled to his favourite grandson, Martin, in Chapter 52, — and then multiple marriages settle affairs between Martin and Mary Graham, Mark and Mrs. Lupin, and the young professional man, architect John Westlock, and the former governess and her brother's housekeeper, Ruth Pinch. A perpetual bachelor, Tom Pinch will live with his sister and brother-in-law — never marrying, but happily (despite his gentle melancholy) practising architecture and the organ. Thus, Westlock is in a sense rewarded for his virtue by settling down with both his best friend and his best friend's sister.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"What John Westlock said to Tom Pinch's sister; What Tom Pinch's sister said to John Westlock; What Tom Pinch said to both of them; and how they all passed the remainder of the day."

Brilliantly the Temple Fountain sparkled in the sun, and laughingly its liquid music played, and merrily the idle drops of water danced and danced, and peeping out in sport among the trees, plunged lightly down to hide themselves, as little Ruth and her companion came toward it.

And why they came toward the Fountain at all is a mystery; for they had no business there. It was not in their way. It was quite out of their way. They had no more to do with the Fountain, bless you, than they had with — with Love, or any out-of-the-way thing of that sort.

It was all very well for Tom and his sister to make appointments by the Fountain, but that was quite another affair. Because, of course, when she had to wait a minute or two, it would have been very awkward for her to have had to wait in any but a tolerably quiet spot; but that was as quiet a spot, everything considered, as they could choose. But when she had John Westlock to take care of her, and was going home with her arm in his (home being in a different direction altogether), their coming anywhere near that Fountain was quite extraordinary.

However, there they found themselves. And another extraordinary part of the matter was, that they seemed to have come there, by a silent understanding. Yet when they got there, they were a little confused by being there, which was the strangest part of all; because there is nothing naturally confusing in a Fountain. We all know that.

"What a good old place it was!" John said. With quite an earnest affection for it.

"A pleasant place indeed," said little Ruth. "So shady!"

Oh, wicked little Ruth!

They came to a stop when John began to praise it. The day was exquisite; and stopping at all, it was quite natural — nothing could be more so — that they should glance down Garden Court; because Garden Court ends in the Garden, and the Garden ends in the River, and that glimpse is very bright and fresh and shining on a summer's day. Then, oh, little Ruth, why not look boldly at it! Why fit that tiny, precious, blessed little foot into the cracked corner of an insensible old flagstone in the pavement; and be so very anxious to adjust it to a nicety! — Chapter 53; Diamond Edition, p. 468.

Commentary

In the original series of illustrations by Hablot Knight Browne, John Westlock and Ruth Pinch occur together in the Chapter 39 illustration Mr. Pinch and Ruth Unconscious of a Visitor" (March 1844); in that same monthly number, Tom is made custodian of a collection of books badly in need of reorganisation. Eytinge has chosen to separate Tom from Ruth in his series of sixteen illustrations because Tom alone of all the younger and more admirable characters does not marry at the novel's conclusion, despite his infatuation with Mary Graham, who marries young Martin. In the British Household Edition, Barnard depicts John Westlock just once early on, in Chapter Eleven, "Stand off a moment, Tom," cried the old pupil. . . . . "Let me look at you! Just the same! Not a bit changed!", where Dickens establishes the close emotional connection between Mr. Pecksniff's perpetual drudge, Tom Pinch, and the former student who, no longer willing to accept the senior architect's exploitation, has denounced Pecksniff and left just prior to Martin's arrival.

The last scene in Sol Eytinge's program is set in Fountain Court at London's Middle Temple, where Tom has been organizing a library for an anonymous benefactor (in fact, Old Martin Chuzzlewit). The bubbling and cheery sounds of the little fountain are a suitable auditory accompaniment to the upbeat mood and multiple marriages of the novel's conclusion. Eytinge's focussing on the romantic plot between the manly, forthright John and the diminutive, "womanly" Ruth (complemented an umbrella of doll-like dimensions, not a regular umbrella, as is the case in the equivalent Furniss illustration, Ruth and Westlock in Fountain Court) is a convenience for introducing the romance between these secondary characters in Dickens's extensive cast of seventy-three. What makes his treatment so interesting, however, is Eytinge's depiction of the little fountain in The Temple as a gigantic aquatic series of jets in the river (rather than in Fountain Court), contrasting the industrial chimneys of Southwark, on the other bank of the Thames. Eytinge's Westlock is very much a respectable young gentleman of the mid-Victorian period, dressed in somber black frock-coat and sporting large sideburns — although hardly as acceptable as portraiture, Furniss's interpretation of Tom's old friend is similar, but he carries a cane. Both the Eytinge and Furniss Ruth lack the charming vivacity of the Dickensian original, who, like Amy Dorrit, is a young woman in the body of a mere girl.

The unusual aspect of the Eytinge illustration, the enormous fountain, may be a deliberate hyperbole or misinterpretation of an earlier description of the fountain ("The Temple fountain might have leaped up twenty feet to greet the spring of hopeful maidenhood," a remark by Dickens in Chapter 45 that Eytinge may have taken literally), or it may have been intended to suggest the elation of the characters, or it may represent an interpretation of Dickens's description based on a civic fountain that Eytinge had encountered, either in New York or in Boston, for the period just after the Civil War saw the development of public monumental fountains in the parks of New York, the Boston Common (e. g., the Brewer Fountain, which was in operation by 3 June 1868, in time to influence Eytinge's conception of the fountain in the Middle Temple), and the newly constructed parks of Boston's South End, notably in the English-inspired residential squares laid out by Charles Bulfinch. Entered off Fleet Street, Middle Temple Lane near London's Embankment leads to the hidden square of Fountain Court, an Edenic oasis of quiet suitable to this union of the sensible lovers; here many times before Ruth would rendezvous with her brother after work. Since the little fountain dates from 1682, the lovers meet in the shadows of the past; having lived as a bachelor at Lincoln's Inn Fields and worked as a clerk in a law firm, Dickens was highly familiar with the area, which he describes in detail in Chapter 15 of Barnaby Rudge, a novel set in the late eighteenth century. Bounded by buildings, the little court with its fountain spouting water eight feet into the air does not afford much of a view of the southern shore of the Thames, so that Eytinge's composition remains an enigma, perhaps born out of his desire to contrast the city's recent past as recorded by Dickens with the modern industrial blight gradually taking hold of London.

Relevant Illustrations, 1843-1924

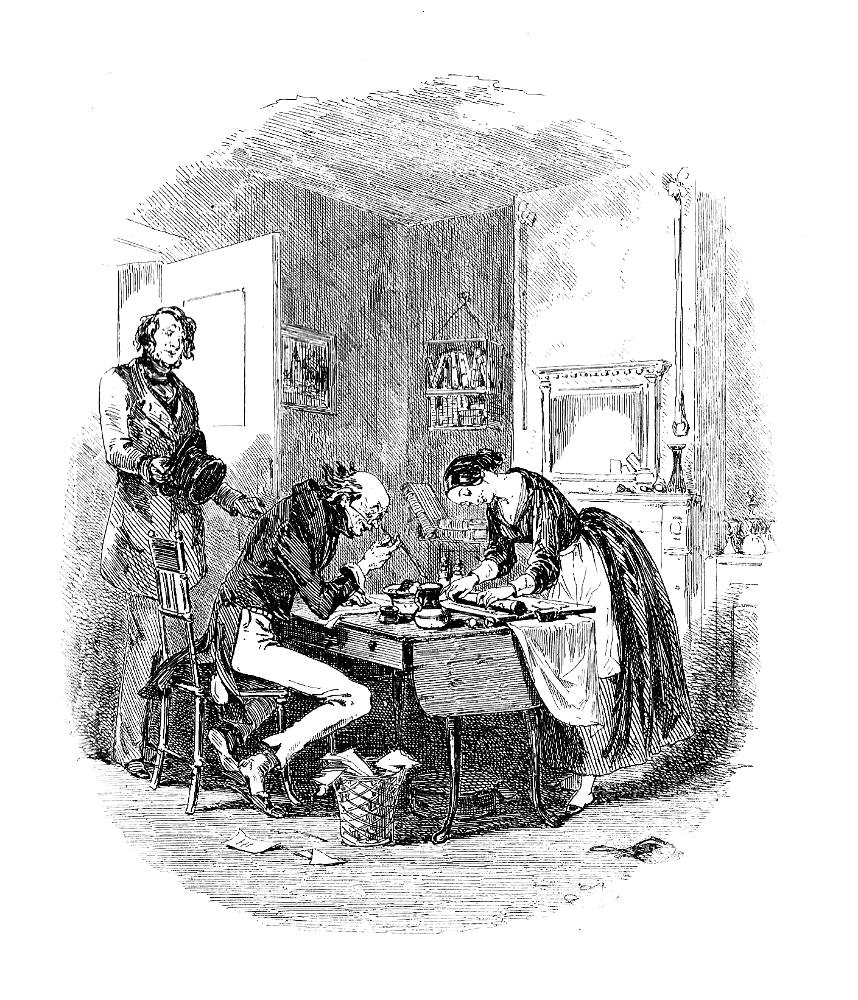

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's realisation of John Westlock's unexpectedly dropping by the Pinches' Islington flat in Chapter 39, Mr. Pinch and Ruth Unconscious of a Visitor (March 1844). Centre: Harold Copping's 1924 colour lithograph of Ruth attempting to make a pudding for her brother, Ruth Pinch Makes a Pudding(Chapter 39). Right: Harry Furniss's realisation of the scene between Ruth Pinch and John Westlock in Chapter 45, with a rather more realistic version of the Middle Temple fountain, Ruth and Westlock in Fountain Court (1910); it looks much the same today. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Fred Barnard's realisation of the later scene, in Chapter 51, when, Ruth Pinch comforts her brother after Martin Chuzzlewit has denounced him for not having protected Mary Graham, Brother and Sister (1872). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

Dickens, Charles. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vols. 1 to 4.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

Dickens, Charles. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Guerard, Albert J. "Martin Chuzzlewit: The Novel as Comic Entertainment." The Triumph of the Novel: Dickens, Dostoevsky, Faulkner. Chicago & London: U. Chicago P., 1976. Pp. 235-260.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Martin Chuzzlewit — Fifty-nine Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

"Middle Temple." Wikipedia. Accessed 4 February 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Temple

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington and London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

_____. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Martin Chuz-

zlewit

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 5 February 2016