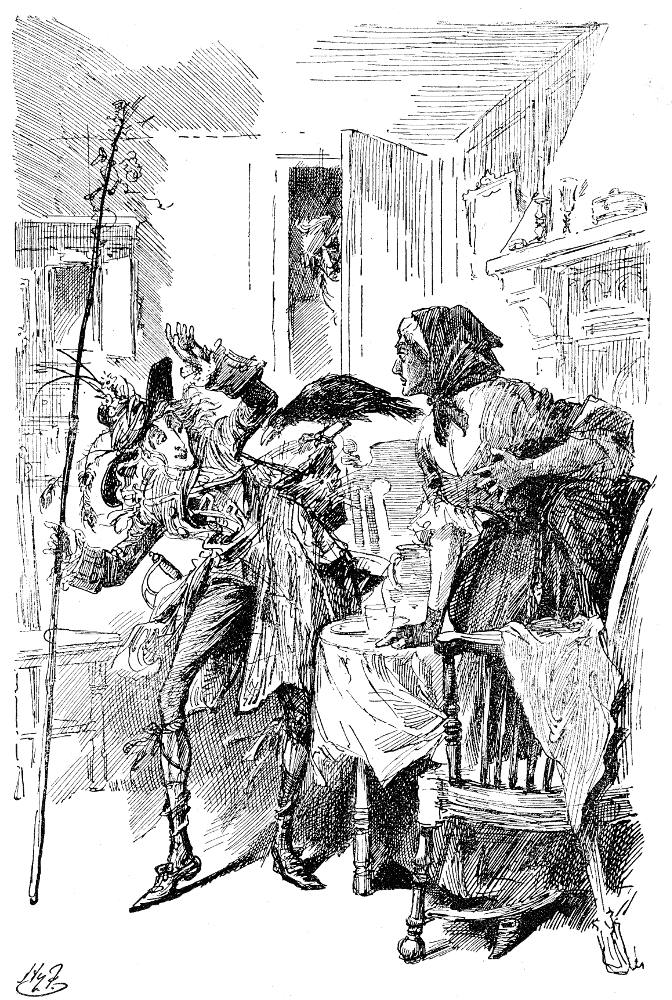

Barnaby and His Mother (frontispiece)

Sol Eytinge

Wood engraving, approximately 3 15⁄16 by 2 15⁄16 inches (10 cm by 7.5 cm), framed.

Frontispiece for Dickens's Barnaby Rudge in the single volume Barnaby Rudge and Hard Times in the Ticknor & Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition.

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image, and those below, without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Context of the Illustration: The Portrait Anticipated

As he stood, at that moment, half shrinking back and half bending forward, both his face and figure were full in the strong glare of the link, and as distinctly revealed as though it had been broadday. He was about three-and-twenty years old, and though ratherspare, of a fair height and strong make. His hair, of which he had a great profusion, was red, and hanging in disorder about his face and shoulders, gave to his restless looks an expression quite unearthly — enhanced by the paleness of his complexion, and the glassy lustre of his large protruding eyes. Startling as his aspect was, the features were good, and there was something even plaintive in his wan and haggard aspect. But, the absence of the soul is far more terrible in a living man than in a dead one; and in this unfortunate being its noblest powers were wanting.

His dress was of green, clumsily trimmed here and there — apparently by his own hands — with gaudy lace; brightest where the cloth was most worn and soiled, and poorest where it was at the best. A pair of tawdry ruffles dangled at his wrists, while his throat was nearly bare. He had ornamented his hat with a cluster of peacock's feathers, but they were limp and broken, and now trailed negligently down his back. Girt to his side was the steel hilt of an old sword without blade or scabbard; and some particoloured ends of ribands and poor glass toys completed the ornamental portion of his attire. The fluttered and confused disposition of all the motley scraps that formed his dress, bespoke, in a scarcely less degree than his eager and unsettled manner, the disorder of his mind, and by a grotesque contrast set off and heightened the more impressive wildness of his face. Chapter III, 28-29]

Commentary: The New Realism Exemplified

In this first full-page dual character study for the first novel in the compact American publication that immediately preceded Dickens's second American reading tour, a whimsically dressed, blithe Barnaby, as always carrying his tame raven in a basket on his back, contrasts his plainly dressed, apprehensive mother. Although the reader is thus introduced to the eponymous character prior to encountering even the title-page, Barnaby and his mother do not make their entrance until the third chapter. Here, Barnaby and the locksmith Gabriel Varden transport a wounded man (apparently the victim of footpads on the high road) to the Southwark home of the Widow Rudge. Dickens describes Barnaby in sufficient detail that even later illustrator (after Phiz in the original serial) would have little difficulty in depicting the mentally challenged, weirdly dressed youth and his pet raven, Grip. In Barnaby Greets His Mother (see below), Ch. XVII, and Barnaby and Grip, Ch. XII, Hablot Knight Browne had provided Eytinge and other nineteenth-century illustrators with useful models for the pair.

Above: Phiz's less dramatic illustration involving Old Rudge's eavesdropping on the widow and her son: Barnaby Greets His Mother (17 April 1841).

Although the text of the novel certainly did not change between 1841 and 1867, its apprehension seems to have shifted from its popular reception as an historical romance (with a pair of couples facing blocking figures) to an exposé of the social and political conditions that spawned the No-Popery riots of 1780 in London. The more modelled and three-dimensional illustrations from 1860 onward reinforce this shift in popular assessment of the novel. For instance, Felix Octavius Carr Darley's 1862 title-page vignettes (see below) treat the figures and situations realistically rather than in the caricatural vein of Phiz, John Leech, and George Cruikshank that dominated book- and periodical illustration in the first half of the nineteenth century on either side of the Atlantic. Whereas Phiz treated Barnaby's homecoming in Chapter 17 as a comic scene on stage, with Old Rudge popping his head out of the closet to better hear his son's account of how he and Hugh had been attempting to trap the highwayman who assaulted Edward Chester the night before, Eytinge in his presentation of the widow and her son eschews such situation comedy and a caricatural presentation of the three principals. Instead, Eytinge presents a dual character study, contrasting Mary Rudge's apprehensiveness (undoubtedly caused by the presence of her estranged husband, literally returned from being thought dead these twenty-two years) and Barbaby's blithe cheerfulness after a day in the Chigwell countryside with his pet raven and Maypole Hugh. The Fred Barnard treatment of the situation in Chapter 17 (see below) is more intensely emotional than, but equally realistic as, the Household Edition illustration of 1874 that exemplifies the New Realism of the Sixties. Barnard, leader of the Sixties Realistic School inaugurated by Fred Walker, attempts to convey the leverage that Old Rudge is using to extort Mary's financial assistance as he pointedly threatens the life of the sleeping boy.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions, 1862-1910

Left: F. O. C. Darley's photogravure title-page vignette of Old Rudge and his estranged wife, "He rattles at the shutters!" cried the man (1862). Centre: Darley's extra-illustration from 1888: Barnaby Rudge and Grip the Raven . Right: Harry Furniss's lithograph for the Charles Dickens Library Edition Barnaby and his Mother (1910).

Above: Barnard's highly charged rendering of Old Rudge's confronting his sleeping son after an absence of twenty-two years: With that he advanced, and bending down over the prostrate form, softly turned back the head (1874).

Relevant Illustrations for this Novel (1841 through 1910)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The Old Curiosity Shop: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Phiz's 72 Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (13 Feb.-27 Nov. 1841)

- Cattermole's Seventeen Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (13 Feb.-27 Nov. 1841)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1862)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1862)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1862)

- O. C. Darley's Barnaby Rudge and Grip the Raven (1888)

- O. C. Darley's Hugh and Dolly Varden (1888)

- O. C. Darley's Old Rudge and John Willet (1888)

- Fred Barnard's 46 Household Edition Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (1874)

- The Charles Dickens Library Edition Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge by Harry Furniss (1910).

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz and George Cattermole. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury and Evans, 1849.

_________. Barnaby Rudge. A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1862. 2 vols.

_________. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

________. Barnaby Rudge — A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VII.

________. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. VI.

________. Barnaby Rudge. Ed. Kathleen Tillotson. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. The New Oxford Illustrated Dickens. London: Oxford University Press, 1954, rpt. 1987.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Barnaby

Rudge

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Created 29 October 2011

Last modified 2 December 2025