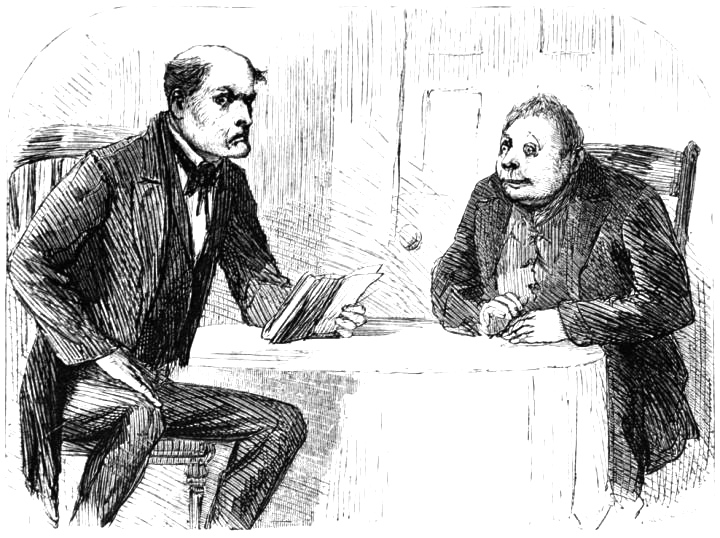

Pumblechook and Wopsle by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Third full-page wood-engraving, from the Diamond Edition (1867) of Charles Dickens's Great Expectations, 10 cm high by 7.5 cm wide. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: After Dinner Pronouncements

A little later on in the dinner, Mr. Wopsle reviewed the sermon with some severity, and intimated — in the usual hypothetical case of the Church being "thrown open" — what kind of sermon he would have given them. After favouring them with some heads of that discourse, he remarked that he considered the subject of the day's homily, ill-chosen; which was the less excusable, he added, when there were so many subjects 'going about.'

'True again,' said Uncle Pumblechook. 'You've hit it, sir! Plenty of subjects going about, for them that know how to put salt upon their tails. That's what's wanted. A man needn't go far to find a subject, if he's ready with his salt-box.' Mr. Pumblechook added, after a short interval of reflection, "Look at Pork alone. There's a subject! If you want a subject, look at Pork!'

'True, sir. Many a moral for the young,' returned Mr. Wopsle; and I knew he was going to lug me in, before he said it; 'might be deduced from that text.' [Chapter IV]

Commentary: The Vexatious Buffoons Take Pork and The Young as their Subjects

This is the third full-page dual character study for the second novel in the compact American publication issued for Dickens's second reading tour. The parish clerk, Mr. Wopsle, yearns to be an actor (parallelling Pip's later desire to become a gentleman), while "Uncle" Pumblechook —not, in fact, Mrs. Joe's uncle, but Joe's — is perfectly content with being a village seed merchant. He is also the family's most successful connection, "a well-to-do corn-chandler" with his own "chaise-cart." According to Pip's descriptions of the pair in chapter 4, Pumblechook is a large-eyed, slow-moving, somewhat out-of-breath, fish-mouthed, sandy-haired, self-important humbug. For his part, Mr. Wopsle has a theatrical air, a bald pate, and a Roman nose. Eytinge depicts the middle-aged pair as a serious, balding, thin man, reading a book, and a contrasting fat man.

The Harper's illustrator John McLenan provided Eytinge with a cartoon-like model of the corn merchant in "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!". However, nowhere in his fairly extensive series does McLenan depict Wopsle. Given their relative positions at the table in Eytinge's illustration, the precise passage illustrated would seem to be the passage describing the Gargerys' family Christmas dinner, given above in Chapter Four.

McLenan may simply have assumed that, like the Hubbles, fellow guests at the Gargerys' Christmas table, Wopsle was not worthy of visual realisation — that he was simply stuffing for the moment when the tableful of guests assembled are shocked by Pip's substituting tar-water for brandy in the bottle from which Pumblechook has just taken a glass. Sol Eytinge, Jr., however, illustrating the novel some six years later for the Ticknor and Fields Diamond Edition, had the advantage of knowing precisely how Wopsle would change, from aspirant to the pulpit to a ham-acting Hamlet and determined leader of the Shakespeare Revival. Eytinge had read the whole book, McLeanan just the initial insatalment.

McLenan understandably regarded Pumblechook as a comic figure, depicting him as an obese bourgeois on spindly legs and carrying the signs of his economic superiority over the Gargerys, his annual tribute of port and sherry. Like many of Dickens's lesser comic figures, Pumblechook behaves so predictably as to be a human machine, and thereby becomes less than human, a mere platitude-making mechanism:

"I have brought you as the compliments of the season — I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of sherry wine — and I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of port wine."

Every Christmas Day he presented himself, as a profound novelty, with exactly the same words, and carrying the two bottles like dumb-bells. Every Christmas Day, Mrs. Joe replied, as she now replied, "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!" [Chapter IV]

This was, in fact, the very moment which McLenan chose for realisation at the head of the novel's second instalment: a thin, almost skeletal Mrs. Joe greeting the Humpty-Dumpty figure of the corn merchant at the door. McLenan undoubtedly realised Pumblechook's comic potential, and drew him accordingly — as a cartoon. Eytinge, on the other hand, would have known to what ends both Pumblechook and Wopsle come later in the novel, probably having read and re-read the 1861 novel before completing his 1867 Diamond Edition commission to illustrate it in the new, "Sixties" manner, with modelled, three-dimensional figures and a more realistic handling. He would have realised that, although Wopsle is a comic figure, too, the village clerk turned Thespian lends himself to a higher form of comedy than caricature, for through Wopsle Dickens satirises the deplorable state of the contemporary theatre later in the story. Eytinge in this drawing knows what Wopsle is and what he will become: an actor always playing to an audience, proud of his deep, sonorous voice and majestic delivery, who mistakenly believes that he can single-handedly revive a moribund stage. In taking the supreme role created by the national bard ("in his highest walk"), Wopsle of full of high purpose — but his less than naturalistic style — his bombast — is ill-suited to the role of Hamlet. Thus, the Wopsle that Eytinge gives us here is not only a parish clerk with the ambition to enter the ministry, but a would-be Burbage (or, perhaps, even a William McCready) who never apprehends his own limitations. Eytinge cannot render Wopsle as a mere caricature (as he has rendered the complacent and none-too-bright Pumblechook); Eytinge's picture represents Wopsle as he is at the beginning of the novel, but suggests what he will later become. Consequently, Eytinge shows him studying a script-sized book which is not likely to be the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, but more probably The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, which he ineptly brings to the boards of an unlicensed theatre in Chapter 31 under the unlikely stage-name "Waldengarver."

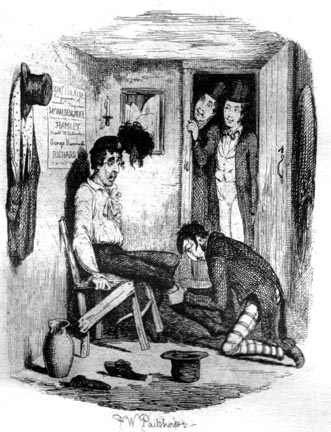

Other Artists' Renderings of the Ham Actor before and behind the Scenes, 1885 and 1910

Left: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration of Wopsle behind the scenes, Pip enters Wopsle's Dressing Room (1910). Centre: Frederic W. Pailthorpe's Robson and Kerslake Edition version of Wopsle as "Waldengarver" having his tights removed: The Flaying of Hamlet (1885). Right: Harry Furniss's portrait of Wopsle doing Shakespeare: Wopsle as Hamlet (1910).

Related Material

- Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations

- Bibliography of works relevant to illustrations of Great Expectations

Other Artists’ Illustrations for Dickens's Great Expectations

- Edward Ardizzone (2 plates selected)

- H. M. Brock (8 lithographs)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (2 lithographs from watercolours)

- Felix O. C. Darley (2 plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- Marcus Stone (8 wood engravings)

- John McLenan (40 wood engravings)

- Frederic W. Pailthorpe (21 lithographs)

- Harry Furniss (28 plates)

- Charles Green (10 lithographs)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Illustrated by John McLenan. Vol. IV. 1 December 1860: 765.

_____. ("Boz."). Great Expectations. With thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson (by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York), 1861.

_____. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Created 2 October 2011 Last updated 4 October 2021