Publication and critical assessments

gnored for more than a century, The Notting Hill Mystery is now widely regarded as an important landmark in the development of detective fiction. First published anonymously in Once a Week in 1862–3, but generally attributed to the little-known writer and publisher, Charles Warren Adams (1833–1903), it is frequently identified as the first of the genre. This claim was made by Julian Symons (1972), for whom its ‘primacy’ was ‘unquestionable’ (63), while others, notably Maurice Richardson (1945), have described it as a progressive example of a whodunnit, ‘more in keeping with [the twentieth] century than the [nineteenth]’ (Novels of Mystery xiii).

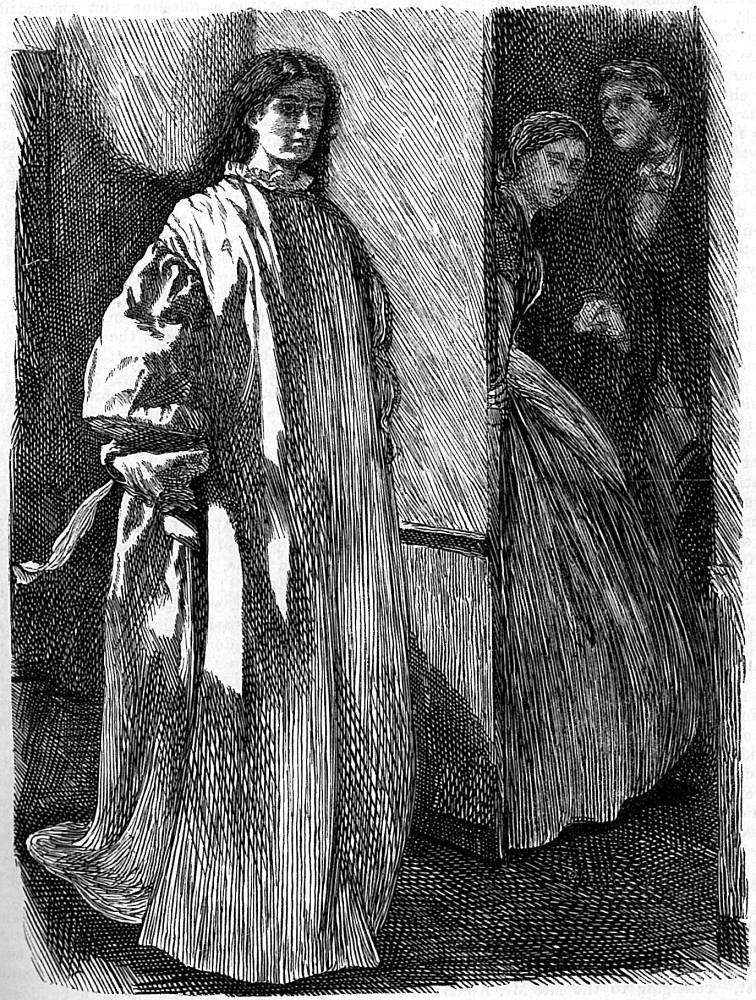

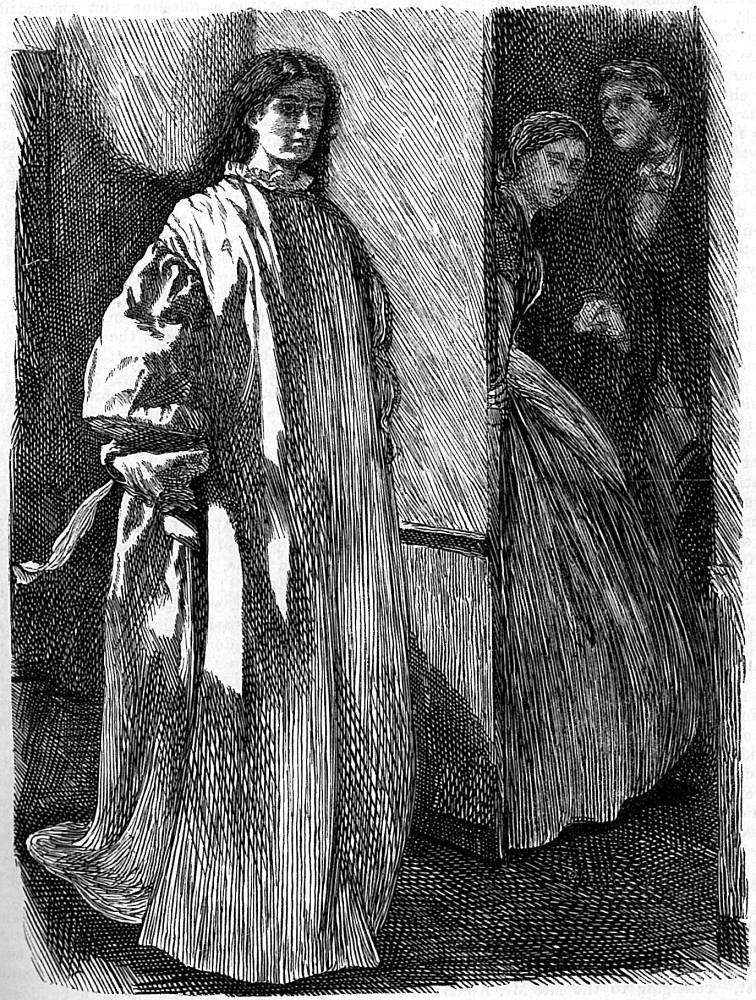

Left: Gertrude in the Wilderness. Right: The Baron hypnotises Rosalie. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

In its own time, however, the tale was viewed as just another example of Sensationalism, a racy thriller in direct competition with such familiar titles as Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White (1860), Ellen Wood’s East Lynne (1861), and M. E. Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862). Endowed with a ‘wildly sensational’ plot (Novels of Mystery xiii) which offers a rich and implausible brew of criminal deception, coincidences, unexpected deaths, mesmerism, substitutions, contemporary settings and a thoroughly foreign villain, it seems to fit neatly within the conventions of the type. As far as contemporaries were concerned it was purely a showing of the lurid and overblown, yet another attempt at ‘convulsing the soul of the reader’ (‘Sensation Novels’ 483).

What is more interesting, perhaps, is the way in which its effects were visualized and enhanced by the accompanying illustrations. Interpreted in seven bold engravings which were drawn on wood by George du Maurier (1834–96) and cut by Joseph Swain, Adams’s text is a prime example of a mid-Victorian thriller which can be read on its own but is significantly embellished and amplified by the visual montage running in tandem with the letterpress. In the italicised address attached to the opening number, the author claims the illustrations were an after-thought, ‘simply added to make the reader’s task more agreeable’ (OAW 29 November 1862, p.617); yet they are far more than decorative, and play an important part in the process of reading. Never intended to be read as a text without its illustrations, The Notting Hill Mystery is only completed, I suggest, by du Maurier’s sophisticated materialization of its Sensational ingredients.

This process of visualizing the tale’s effects has been identified in passing by a number of commentators. Forrest Reid describes the illustrations as ‘sinister’ and ‘poetic’, creating a ‘veil of dark horrors’ (175); Leonée Ormond calls them ‘powerful’(138); and Paul Goldman comments on their ‘great panache’ in the ‘waxed moustache or melodramatic thriller style’ (117). These assessments suggest the images’ lurid and imposing nature, but, beyond generalizations, do not consider their function as literary illustrations, or their place within a wider historical context. As so often happens, there is tendency to view them as independent units, pieces of design in their own right while not considering the purposes for which they were intended.

The present analysis explores du Maurier’s approach in much greater detail than in previous criticism. I focus on the complex intermingling and interactions between the two elements; how du Maurier’s designs construct Adams’s text as a thriller; how they improve and complicate the range and implication of his writing; and how, through a process of allusion, they frame the novel in Sensational terms. I also explore the publishing contexts in which the work was produced and how this affected du Maurier’s visual strategies.

du Maurier, Lucas, Working Practices, and Once a Week

u Maurier’s illustrations were produced within a framework of professional competition and editorial demands. Like so many of the artists at work on Once a Week, and desperate for employment during a lean period in which he strove to establish himself as a regular name at the offices of Bradbury and Evans (Cooke, Illustrated, pp. 56–61), he was offered the commission following a period of assessment. Samuel Lucas, the magazine’s difficult and demanding editor, appointed him after a period of ‘trial’ (The Young George du Maurier 179), and only gave him the brief when he was convinced of du Maurier’s appropriateness for this particular task. Lucas may have asked him to do preparatory designs, or he may have judged the artist’s suitability on the basis of his earlier commissions. du Maurier’s work at Once a Week, particularly for Elizabeth Blagden’s thriller, Santa (August–September 1862), had already demonstrated his ability to visualize a sensational fusion of intrigue and modernity, and this experience made him an ideal candidate as an interpreter of the text at hand.

His qualities may have been obvious to the editor, who was centrally concerned with the question of artistic aptness. As a theorist of illustration, whose Times reviews explored the nature of graphic representation, he actively sought the best possible fit between his illustrators’ styles and the material to be interpreted. Lucas envisaged this process as a highly prescriptive procedure (Illustrated 100-106), and in offering the work he directed du Maurier to illustrate the text in specific ways.

du Maurier was asked to visualize The Notting Hill Mystery, his first ‘long serial’ (Young 188), in a style which was self-consciously dramatic and eye-catching. Although Lucas disliked Sensationalism (Buckler 928), he realized the economic need to maintain Once a Week’s position by appealing to ‘popular taste’ (936), and du Maurier was probably appointed to provide striking illustrations that would draw attention to Adams’s intricate crowd-pleaser. Such designs unashamedly set out to sell the magazine (Wynne 162) by breaking up the congested columns and converting the act of reading into a source of visual pleasure. Figured as half-page designs of frenetic groupings, baroque intersections of space, violent action and absolute contrasts of black and white, du Maurier’s illustrations form a startling contrast with the small print and claustrophobic uniformity of the type-face. Rising to the task, his compositions become ever more arresting as the narrative unfolds and moves towards a climax. This includes a policeman finding Aldridge’s body in the street (27 December 1862, p.3), as well as the illustration of the hypnotized Madame making her dreamy way, in a state of titillating undress, to ultimate doom in the grip of poison (10 January 1863, p.57).

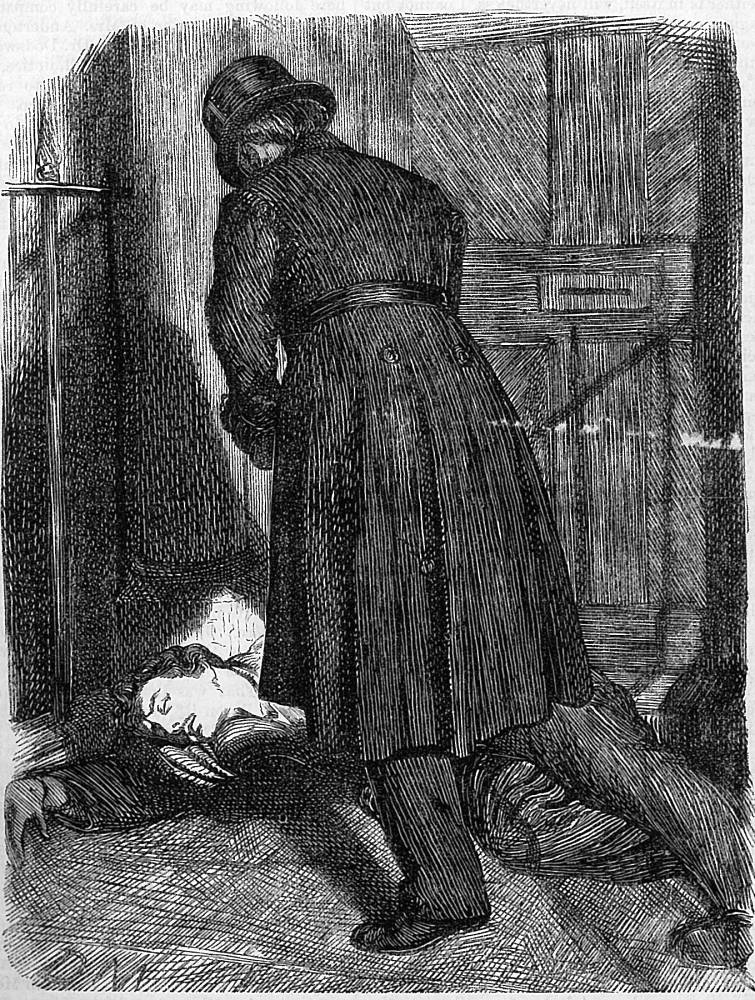

Left: The policeman found him lying on the doorstep. Right: Madame hypnotised. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

This emphasis on the transgressive and incongruous provides the sort of visual hyperbole that was intended to attract and stimulate the tastes of a middle-brow audience, no matter how excessive.

However, Lucas’s aesthetics extended well beyond the idea of visual promotion. He also insisted that the illustrations should provide a detailed representation of the written text. He wrote in detail of the notion of mimetic matching in which the designs provide an exact reflection of the author’s fictional world, and. he expected du Maurier, as he expected of all of his illustrators, to provide a ‘powerful translation’ of the writer’s words. Such an ‘accord’ (‘More Gift Books’ 12) was crucial and Lucas directed the artist should never ‘mistake’ or ‘contradict’ the messages ‘confided’ by his collaborator (‘Illustrated Books’ 10). What Lucas demanded, in short, was the production of a paratext, a literal mirroring or re-visualization intended to, repeat and underline the information already contained in Adams’s letterpress. Complying with this requirement was more problematic than it might seem.

To some extent du Maurier provides a literal translation of the narrative, as well as some of the characters and some of the settings. The chief difficulty, however, lies in the fact that although the story has a distinctive narrative with multiple settings and characters, it is curiously resistant to visualization. Unlike most Sensational texts, it has very little visual detailing: figured as a series of terse accounts, often in legal or insurance jargon and sometimes in the kitchen-talk of servants, it has no ekphrastic descriptions of the sort typically found in the highly pictorial fictions of Braddon, Collins, and Le Fanu. There are none of the visual clues and prompts found in Collins’s descriptions of Mr Fairlie in The Woman in White (65–66) or Braddon’s description of the exterior of Audley Court (Lady Audley’s Secret 1–4), or even in the character-painting of Reade. There is no ‘picturing’ or ‘painting in words’ of the type so frequently remarked by contemporary reviewers of the genre, and the illustrator has only the barest of information to which he can respond. Only offered as a short novelette, Adam’s narrative is a bare outline, and, as far as the artist was concerned, a near-blank. In the words of an anonymous critic writing in the London Review in response to the first book edition, this sparse and undeveloped writing is markedly deficient in its appeal to the eye, subsisting as little more than ‘a skeleton of a story, which requires to be clothed in flesh and blood’ (‘Novellettes’ 178).

du Maurier was faced, in other words, with a challenging task at odds with Lucas’s naive belief in the illustrator’s capacity to make a straightforward ‘translation’ from one medium to the other. Nor was there help from the author. The editor, who wanted to impose his own credo, actively discouraged such professional collaborations (Cooke, Illustrated 106); there is no evidence of any meeting between the two partners, nor of any authorial intervention or influence. The artist’s response was nevertheless a highly creative one. Left to his own devices, though probably given the advantage of reading the entire manuscript before it was divided into serial parts, he set about visualizing the material as part of a composite text in which he foregrounds aspects of Adam’s writing, while also providing new and important information which is not contained in the letterpress but is essential to make sense of it. Such extra-diegetic additions take the form of visual descriptions created without the advantage of any written descriptions, the enhancement of characterization, and other details and emphases. Indeed, he re-figures the serial as complex double-art in which some of the most significant nuances are enshrined in the images rather than the words, and the whole effect can only be understood by reading the two sets of signs as part of an integral unity. Commissioned to illustrate a ‘skeleton’, he sets out to cloth it in the ‘flesh and blood’ of visual material, translating it into pictorial terms that give it the clarity of a montage and the complexity of a developed piece of Sensational fiction.

This position is fraught with inconsistencies, but typical of du Maurier’s experimentalism. In his response to other commissions – notably Eleanor’s Victory – he actively tried to comply with editorial emphasis on paratext and replication (Cooke, ‘George du Maurier’s Illustrations’, 90–91), but here he contradicts the mid-Victorian notion of the author’s dominance and the artist’s subservience. On the contrary, he challenges and perhaps even appropriates the role of a writer. Taking control of his material, he interprets and recasts it in his own terms, going well beyond the status of a co-narrator.

Even at this early part of his career he was considering the idea of the shared roles of writer and artist, and his correspondence reveals how he believed he could write better poems than those he was asked to illustrate (Young 36). As early as April 1861 he had proclaimed that his ‘real line will in the end be...simply to write and illustrate myself’ (Young 39), a desire he would ultimately realize in the form of his novels, Trilby (1894), Peter Ibbetson (1892), and The Martian (1898). In the case of The Notting Hill Mystery he does not literally write the words, but his treatment is transformative, making it as much his utterance as Adams’s.

His strategy is one of development, of drawing out and enhancing the fiction’s Sensational tropes. We do not know if Adams were knowledgeable of the genre beyond his thin representation of some of its conventions, but du Maurier clearly understood how the writing could be enhanced by intensifying its Sensational elements and by foregrounding its effects through a process of allusion, creating a linkage to texts such as Collins’s The Woman in White (1860). Such visualization of literary codes enhances the text and, as noted earlier, allows the reader/viewer to make connections with a series of ready-made signs. As Leighton and Surridge aptly remark, illustrations ‘could manipulate these tropes, thereby helping to define’ – or in this case actively construct – ‘the generic expectations with which readers’ (‘The Plot Thickens’ 71) approached such fictions. du Maurier’s amplification of The Notting Hill Mystery can most effectively be read, then, by examining his development of the primary, Sensational elements of narrative, setting, and character.

Sensational Story-Telling, Settings and Characters

dams’s text is in many ways a typical piece of Sensation in which the main emphasis is on the writing and decoding of narrative. As contemporaries observed, its interest primarily resides in the ‘ingenuity’ (The Reader, qtd. in advertisements, Arnold 354) and ‘complication’ (The Guardian, qtd. Ellis 349) of the plot, compelling ‘every individual reader, as in the game called solitaire … to pick out his own way to the elucidation of the proposed puzzle’ (‘Novelettes’ 178). This purpose is central to the reading and writing of mystery, and for the artist of Sensationalism (Leighton and Surridge, ‘Transatlantic’ 217) this material was intensely problematic. Put crudely, du Maurier had to depict a series of scenes while not explaining the story’s unknowns: he had to show, but he was not able to reveal.

His approach was characteristically inventive. Contradicting the usual role of illustration – which was traditionally intended to illuminate and explain – he reverses its function, using it not as a means to help the reader to ‘unravel the mystery’ (OAW, [29 November 1862]: 617) but as a visual series which intensifies the written text by heightening its uncertainties, offering false clues, and continuing the process of obfuscation. He offers the viewer with an essentially baffling equivalent to the letterpress: Adams presents a ‘carefully-prepared chaos’ (‘Novelettes’ 178) of testimonies, accounts and documents, and du Maurier visualizes what appears to be a disjointed jumble of scenes, characters and possible narratives. The reader of the written text is forced to evaluate what is significant or not significant, and du Maurier dramatizes what may – or may not – be key moments. The viewer progresses through a kaleidoscopic range of possibilities that moves through experiences and events of all sorts, from the opening design of the stricken Gertrude at the lakeside ([29 November 1862]: 617) to mesmerized languor (6 December 1862: p.645), the sick-room ([13 December 1862]: 673), and a figure of a policeman on the street.

Left: Gertrude in the Wilderness. Right: Mr Anderton supporting his wife in his arms’. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

All of these images have changing characters and no recognizable unities of setting; the writing shifts between narrative voices and locations, and the illustrations take the viewer into a parallel world of nightmarish events that force the viewer to try to make sense of them. Simply by looking from letterpress to text the reader-viewer is engaged in a game of bluff and double-bluff; the process of checking, of looking for visual confirmation in the designs, is deliberately confounded; all, everything, or nothing could be the telling clue. In Leighton and Surridge’s term, du Maurier’s illustrations ‘thicken the plot’, making it not transparent but opaque, a field of uncertainties. Often literally wrapped in a suggestive chiaroscuro, a metaphor for the unknown or mysterious, they dramatize the difficulties of ‘seeing’ the truth, of discriminating what is truthful when nothing can be clearly ‘seen’.

Of course, we cannot know the thought-processes of the original audience, but we can infer some of the questions the illustrations pose. In the illustration of the unconscious Aldridge, for example, we have a number of clues which could be revealing. The letterpress notes how the character is essentially thrown out by the Baron following Aldridge’s ‘foolish story’ and the quarrel between them (27 December 1862, p.3). With the advantage of hindsight we can deduce that the Baron drugged him, but when the original viewer saw this design s/he would only have been offered a number of cryptic clues. Why is the character on the street? How is this event linked to the Baron, who, despite insisting on Aldridge’s leaving, is described as ‘kind’ and ‘without a hard word’ (3)? Looking more closely, the viewer might note Aldridge’s pallid, lifeless face, the sign of a more troubling condition than mere drunkenness. This might be linked to Gertrude’s blanched face in the first illustration, or at any rate suggest a physical collapse demanding some explanation. du Maurier’s prominent positioning of the policeman also seems suggestive; the text merely notes how he is found by the officer, but why does du Maurier make him into a dynamic figure, his face concealed, as he seems to bear down on the prostate man? The pose, half-running, half-surprised, suggests urgency: why? To help a drunk? The viewer might speculate that the police are somehow involved beyond a casual piece of urban routine, and (by logical extensive) is their presence connected with the Baron? The illustration implants a number of possibilities leading from and expanding the terse reportage in the text, and all of the images invoke the feelings of suspicion, thoughtfulness and the desire to know.

Functioning to enhance the story, the illustrations also intensify the emotional extremes associated with Sensationalism. Adams underplays his thrilling moments and gives his prose a measured and unemotional texture. However, du Maurier converts the flatness of the style into the extremity of the mid-Victorian thriller by visualizing some of the most startling moments. As we have seen, he does not reveal the plot’s mysteries, but he does make the text into a staccato series of climactic tableaux.

His strategy is partly one of selection, and partly one of elaboration. His developing of textual detail can be explained by comparing written information with its visual re-inscription in the opening and closing designs. In the first of these we are told of Gertrude’s suffering in a part of the ground known as ‘the Wilderness … stretched upon the turf at the edge of the lake’ (29 November 1862, p. 620). There is no elaboration in this blunt reportage; in itself, it could barely be described as a moment of horror and pain. In the illustration, conversely, du Maurier converts the scene into a semi-hysterical vision of shock and despair. The dying Gertrude collapses helplessly, with the arms of the maid and the postman forming a muscular contrast with her limp hand; her face is a blank white outlined against the hatching of the lake; and her suffering is observed by the gaunt figure of Helen, framing the left of the composition. In Adams’s text this episode is reported in conventional terms, but du Maurier foregrounds its effects by showing a vulnerable middle-class woman in a threatening environment.

Her unconscious hand pours out the deadly draught [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The heightening of the text is similarly displayed in the final illustration (17 January 1863, p.85), which shows Madame R’s death. Adams describes her demise as a ‘horrible’ and ‘instant’ (91), but du Maurier intensifies the moment to a new level of horror. Focusing on the idea that the acid-poison ‘shrivels’ (91) her, he shows her body as a distorted form. In contrast to her holding of the draft, as specified in the text, he depicts her clasping the leg of a chair. Her hair is dishevelled; humiliated by her appearance in her nightgown, a breaking of codes of propriety, he places her in the foreground of a baroque composition, unsettling the reader-viewer by projecting the design’s imaginative space into the real space of the observer.

Such effects engage the reader-viewer in a drama of unfolding grotesquerie, and the impact is further heightened by the illustrations’ positioning at the beginning of each instalment. This physical layout materializes the artist’s attempts to unsettle and excite the audience by showing what is about to come. As Leighton and Surridge have explained, Sensational illustrations build tension and anticipation by their proleptic siting (‘The Plot Thickens’ 67; ‘Transatlantic’ 210). Leighton and Surridge go on to note how the readers’ expectations are then matched – or mismatched – with the text that follows (Moonstone 210). In the case of The Notting Hill Mystery, as I have argued, the illustrations foreground the Sensational extremis, providing the fiction with a thrilling intensity that is powerful enough to sustain the reader when he or she finds the parallel, and purely journalistic, information in the letterpress. The text insists on its truthfulness, the product of sober facts, investigations and legalities: but du Maurier ensures its status as a full-blown thriller is physically kept, in the form of his harsh and discordant designs, before its readers’ eyes. The text deals with ‘facts’, the illustrations with emotions.

The illustrations work, then, to strengthen the text’s Sensational credentials not only by foregrounding its moments of climax and excitement, but also, through a process of juxtaposition with the letterpress, by pointing to its paradoxical tension between emotionalism and realism. Leighton and Surridge have noted how such illustrations ‘play a key … role in constituting the intense generic interplay of sensation and realism’ (‘The Plot Thickens’ 67), and du Maurier’s designs, as exemplars of their type, fuse these two apparent opposites. We have seen how he highlights the text’s emotional content, and he is similarly thorough in his response to the writing of the real. Adams provides addresses, dates and extremely limited outlines of the physical mis-en-scéne; but du Maurier firmly roots the action in a series of well-defined settings which, in the absence of textual direction, he is compelled to invent. His emphasis is one of factual validation: the story is supposed to be the ‘truth’, so du Maurier places the characters in a series of places which look as if they might indeed be representations of real locations. We are taken into a range of plausible settings including a landscape (1862, p. 617), an urban street (1), the servants’ quarters and corridors at home (10 January 1863: p.57), and comfortable sitting-rooms (6 December 1862, p.645). du Maurier particularly stresses the notion of contemporaneity. Adams claims the illustrations were not made simultaneously with the events they represent (1862, p.617), but the artist’s approach is one of journalistic immediacy. The text has the texture of a scandal, a crime living in the present, and du Maurier gives his images a tabloid immediacy to foreground the writer’s emphasis on topicality and modernity. Influenced by Frederick Sandys, who advised him to copy from reality wherever he could, his illustrations have a Pre-Raphaelite directness: the costumes, décor and furniture are contemporary, and he enlivens his compositions by focusing on specific, transient moments such as the policeman discovering the man in the street, the very moment when the Baron grabs the servant’s arm, and the instant as Mrs Anderton swoons into her husband’s arms. His illustrations are thus deployed to assert the everyday realism which characterizes the genre, endowing his text with the physical immediacy, the placing of the unexpected within the prosaic which is so important in creating Sensationalism’s modernist surfaces.

More specifically, du Maurier roots the world of criminality, the accounts of an unfolding mystery told by characters who can only be read as voices, in the familiar domain of the bourgeois home. This is a world that would have been recognized by the reader-viewer as he or she engaged with Once a Week, at the fireside, examining the scenes of middle-class interiors, and wondering, perhaps, if such events could be enacted in their own domestic space. The illustrations are used, in short, to project the fiction’s universe, converting Adams’s thriller into a thriller which presents a threat within the fabric of the journalistic, a menace in the ordinary, a fearfulness in the here and now. In a words of Mansel’s celebrated review in The Quarterly, the best effects are generated by ‘Proximity’ made thoroughly effective by ‘laying the scene … in our own times’ (pp.488-9). With their hard materiality and prosaic detail, the illustrations ensure Adams’s text is given this precisely this immediacy within the imaginative lives of its original readers.

du Maurier struggles with a greater problem in the writing of character. I have noted how the text lacks detail of either narrative or setting, and the author gives practically nothing in terms of visual description of how his dramatic personae appear, and absolutely nothing of their inner motivations In this respect the story is not unlike many of the genre; as Mansel remarked, ‘deep knowledge of human nature [and] graphic delineations of individual character’ are not necessarily features of Sensationalism (‘Sensational Novels’ 486). In the case of this text, however, the artist has little indeed to work with; the characters are ‘scarcely indicated’ (Guardian, qtd. Ellis 349); ‘numerous names are introduced [but] the magnetic influence of a life-like [personality is entirely] wanting’ (‘Novelettes’ 178). Nevertheless, he seems to have wanted to endow these characters with some of the complexity found in many of the more accomplished examples of the genre, notably those by Collins and Braddon. Presented with only the thinnest of character-writing, du Maurier’s aim, it can be argued, was to infuse the personae with the depth that is offered in the form of characters such as Fosco in Collins’s The Woman in White or Braddon’s heroine in Lady Audley’s Secret.

His solution, as with the other aspects of his treatment, is visualize what little he was given, draw on example, and invent new material. As I suggested earlier, he read the manuscript in its entirety, so he was able to identify the outline of the characters’ essentials. This information enabled him to picture at least some of the important features of the main players: for instance, Mr. Anderton’s torment as the first victim is conveyed by showing him as a distracted man (12 December 1862 676), and with no other description to work with the artist endows him with a sensitive physiognomy. In the scene where he cradles his wife (12 December 1862 673), he is portrayed as a man with a high forehead, the conventional sign of nobility and compassion, and a well formed profile. In the case of the Baron, conversely, the image suggestively visualizes his power: avoiding the temptation to depict him as a stereotypical villain, du Maurier shows him as a bulky middle-aged man with a large head whose physical presence graphically conveys his domineering manner.

The Baron’s menacing encounter with Sarah Newman. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

This notion is dramatically embodied in his confrontation with Sarah Newman. The frightened servant describes how he intimidates her by walking straight up to her, invading her space, and taking her hand (26 December 1862, p.706). The illustration represents this action (701), but adds more in the form of his forward stance, dominating the composition, and forcing his victim to recoil. Most of all, du Maurier emphasises the medium of his power, endowing him with an intent gaze. The womens’ suffering is similarly depicted by focusing on their prostration and emotionalized gestures, in every treatment suggesting a physical materiality which provides a distinct sense of their inner lives and providing an extra-textual range of expression.

In this respect the illustrator adopts a strategy of visualization which, as he explains in ‘The Illustration of Books from the Serious Artist’s Point of View’ (1890), was focused on the graphic registration of characters as if they were real. ‘The little figures … are voiceless and cannot move [but] the arrested gesture, the expression of face ...may be true to nature [and] may be as graceful, or grotesque, or humorous, or terrible as people in real life’ (350). Once again, du Maurier applies and invokes this convention as a way of reinforcing the text’s place within the genre. Writers such as Le Fanu deployed a complicated picturing in words of figures such as Uncle Silas (Uncle Silas, 1864), and du Maurier provides graphic picturings, descriptions in black and white, rather than words, which act as a distinct and recognizable equivalent to the Sensational writing of its key figures. The illustration of the characters is further complicated by its reference to a number of visual sources in literary form, and in the form of visual art.

These allusions are principally used to establish the characters’ credentials by linking them to the personae in Collins’s The Woman in White (All the Year Round, 1859–60). Essentially the Ur-thriller of its time, this provides a source which would have been recognized by the mid-Victorian audience. Contemporary periodicals such as The Athenaeum noted how Adams’s book seemed to have been modelled on Collins’s prototype (qtd. Casey, pp. 3–4). Collins’s story of substitutes, fake aristocrats and a villainous plot to embezzle a fortune is clearly echoed in the plot of Adams’s text, and du Maurier strengthens this connection by visualizing some of the characters as if they were taken from the original book. As noted above, he literally puts flesh on Baron R, but as a physical type of the Powerful Man he is probably based on Wilkie’s description of Count Fosco. Collins describes his villain as having a face of immovable power (Woman in White 197), and du Maurier endows his creation with a monumental head and static manner. Most of all, he gives his character Fosco’s extraordinarily powerful eyes (197). The Baron’s mesmerising gaze is as overwhelming as the Count’s. His treatment of the Baron, as a domineering physical presence, also evokes Fosco’s threatening and insidious manner as he invades the space of female characters, a connection readers must surely have recognized. Like a character stepping from one text from another, du Maurier’s Baron R is essentially Fosco re-drawn, bringing with him a series of ready-made associations. Without explication in Adams’s text, the picturing of the Baron is a sort of fleshy ghost, a pictorial re-casting and animating of the thin portraiture.

Madame hypnotised. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

du Maurier also strengthens the book’s Collinsian reference by linking Madame R to Collins’s type of Sensational dementia, Anne Catherick. This connection is partly made by drawing on descriptive details in The Woman in White. When she first appears to Hartright, Collins describes his character as a woman dressed from head to foot in white garments with a colourless, youthful face, ‘meagre and sharp to look at’ (Woman in White 15); and du Maurier similarly represents his doomed young woman as a half-mad figure with staring eyes, wrapped in the whiteness of her night-gown (10 January 1863, p. 57). Linked to Anne through a process of resemblance, du Maurier’s Madame is aligned with the idea of the Demented Woman – the woman who is borne down by madness or the imposed madness of hypnotic trance. In essence, du Maurier visualizes Anne as if he were illustrating Collins’s words, but applies his interpretation of another writer’s description to the writing of Adams.

More complicated still is his allusion to art; Madame may have been modelled on Collins’s original, but she is also derived from a painted image. Richard Dorment has argued that the illustration of the hypnotized Madame is derived from Whistler’s Symphony in White No.1: The White Girl, (National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA), a picture du Maurier probably saw during his time as Whistler’s flat-mate in the early sixties (98). Comparison of the two definitely shows some distinct similarities. du Maurier’s figure is essentially a reversed pose of Whistler’s girl while reproducing her blank expression (pp. 77-78); the faces are extremely similar; the whiteness and elongation of the figures is closely linked; and both have the same cascading and untied hair. What we have here, in other words, is a complex piece of interpictoriality. du Maurier alludes to Whistler’s picture because in the public mind it was associated with The Woman in White; when it was exhibited at the Berners Street Gallery in the early part of 1862 critics initially thought it to be a painted illustration of Anne Catherick, and, although it bore no relationship to this source, the audience at large read the painting as if it were a showing of the Collinsian original. By drawing on a picture classified in these terms, and one which was routinely described as ‘sensational’ (Dorment 76), du Maurier deploys another form of visual interconnectedness as a means of highlighting the Sensationalism of Adams’s text by linking it to what was popularly understand as a picture of one of Collins’s characters.

This visual frame of reference reinforces the reader’s expectations in the most powerful form. By drawing on Collins’s novel and by quoting what was widely – if erroneously – thought of as a showing of his mysterious character in a dramatic and imposing way, he again positions Adams’s novel within a range of signs denoting Sensation. Deborah Wynne has shown how one of du Maurier’s illustrations to Gaskell’s Wives and Daughters, (The Cornhill Magazine, November 1865, facing p.513) is based on Augustus Egg’s Past and Present (1856; Tate Britain, London), and in his showing of the present story he again exploits the readers’ knowledge of other visual texts (Wynne, p. 163). Such borrowings allow him to re-inscribe the visual conventions of the genre and re-work the textures of Adams’s tale in ways which insist on its identification.

The representation of Madame R as if she were Collins’s Anne is likewise important in so far as it reminds the reader-viewer of Adams’s Collinsian emphasis on the manipulation of women. The Woman in White can be read as a tale of female weakness, a story of Anne and Laura’s humiliation; and in invoking this model du Maurier emphasises the thematic linkages between the text at hand and Collins’s novel. The Woman in White involves the suffering and manipulation of doubles, and in Adams’s tale twin sisters are exploited for a similarly criminal end; in The Woman in White, this process is enacted by Percival Glyde and Count Fosco, and in du Maurier’s designs the emphasis is once again on male subjugation of women. Following the Collinsian exemplar and invoking the treatment of women as it appears throughout Sensationalism, most notably in novels such as Wood’s East Lynne, he casts his text within a central discourse of sexual politics that lies at the heart of the genre.

His illustrations dramatize this situation by representing all of the female characters in compromised positions controlled by men. The foremost male character is of course Baron R, who is shown in two distinct scenarios. In the first of these we see him mesmerising Mrs Anderton via the medium of Rosalie. This event is described in the prosaic terms of Frederick Morton, a soldier; invited to the family home, he merely notes, in words suggesting tenderness or even eroticism, how the Baron imposed a flow of ‘mesmeric fluid’ which makes Rosalie go to sleep but keeps Mrs Anderton in a ‘refreshing hypnotic trance’ (OAW 6 December 1862, p.647). In the illustration, however, there is a much greater sense of male dominance and the overpowering of the subjects. The Baron leans heavily over them with his hypnotising hand directed strangely towards Rosalie’s sleeping face, while his other holds the sleeping figure’s wrist. Both are pinned down, as it were, by the mesmerising gaze. The illustrator also shows the Baron holding the arm of the servant Sarah Newman as she recoils from his gaze.

This emphasis on the masculine gaze is especially important, because all of the women – with the exception of the servant Sarah – are unconscious, objects to be looked at and controlled while they themselves are incapacitated. In the second illustration, with the two women under the power of mesmerism, we see them with their eyes shut, possessed by the mesmeric trance imposed by a man. The picture of subservience is further suggested by the voyeuristic scrutiny of Mr Anderton and Frederick Morton, who look on as if they were watching a mildly amusing party-game rather than a piece of psychological therapy. Mrs Anderton is viewed by her husband and male helper, while in the penultimate illustration we are shown the unseeing Madame deep in a hypnotic trance, her very incapacity heightened by her unseeing somnambulism while she is spied upon by the servants peering from behind a door. More often still, the female characters are simply overwhelmed by frailty and illness. We see Sarah Bolton collapsing by the lakeside; Mrs Anderton in her husband’s arms; the hypnotised sisters; the mesmerised Madame; and the same figure lying dead after she has taken the fatal poison. du Maurier’s reading, then, is one in which he foregrounds the cruelty directed at women. This minimises the interest of the crime story, as such, and places the tale as a typically Sensational account of female powerlessness and the vulnerability of the female body. As Leighton and Surridge explain, one of the key features of the genre was its emphasis on ‘physical collapse’ (‘Sensation and Illustration’, p.541). du Maurier places this concern at the forefront of the writing.

Effects and After-Effects

ith their bracing mixture of realism, mysteriousness, emotional extremes, and the exploitation of women, du Maurier’s illustrations construct Adams’s tale as a fully-developed piece of Sensationalism. Responding to minimalist writing, they heighten its effects and strengthen its place within the genre. Essentially, this picture-serial is the completed version: taken as a composite, the end result is far more imposing and dynamic than the unillustrated imprints of later years. The text without its designs is stripped of much of its information and most of its impact. A reader of the un-enhanced tale might focus on the elements of detection and surmise, but a viewing in conjunction with the illustrations enacts the characteristically Sensational process of ‘electrifying’ (‘Sensation Novels’, p.498), of dazzling the eye, confounding expectations and materializing the genre’s typical aim of generating ‘excitement, and excitement alone’ (482). Febrile and dynamic, the illustrations produce the effects of anxiety (Wynne 47), the central ingredient in the construction of the ‘trademark nervous reader’ (Leighton and Surridge, ‘Sensation and Illustration’, p.541). The fact that they are so rarely reproduced diminishes the status of Adams’s text and consigns it to a minor standing, eclipsed by the more famous novels of its time.

Works Cited

[Adams, Charles Warren]. ‘Felix, Charles’. ‘The Notting Hill Mystery.’ Once a Week (November 1862–January 1863). London: Bradbury & Evans, 1862–3. Reprinted as: ‘Felix, Charles’. The Notting Hill Mystery. London: Saunders & Otley, 1865. This edition did not have the illustrations. The following two modern reprints similarly lack the visual material: The Notting Hill Mystery. New York: Arno, 1976; and London: British Library, 2011.

Arnold, Arthur. The History of the Cotton Famine. London: Saunders & Otley, 1865.

Braddon, M. E. Aurora Floyd. London: Ward & Lock, 1864.

Braddon, M. E. ‘Eleanor’s Victory.’ Once a Week (March–October 1863). London: Bradbury & Evans, 1862–3.

Braddon, M. E. Lady Audley’s Secret. 1862; Oxford: World’s Classics, 1982.

Buckler, William E. ‘Once a Week under Samuel Lucas, 1859–65.’ PMLA 67 (1952): 924–41.

Casey, Ellen Miller. “‘Highly Flavoured Dishes’ and ‘Highly Seasoned Garbage’.” Victorian Sensations: Essays on a Scandalous Genre. Eds. Kimberley Harrison, Richard Fantina et al. Ohio Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2006, pp. 3–12.

Collins, Paul. ‘Sunday Review: The case of the First Mystery Novelist.’ The New York Times [www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/books/review.collins-t]. Accessed 12 November 2011.

Collins, Wilkie. The Woman in White. 1860; Oxford: Oxford Classics,1980.

Cooke, Simon. ‘George du Maurier’s Illustrations for M.E. Braddon’s Eleanor’s Victory in Once a Week.’ Victorian Periodicals Review 35: 1 (Spring 2002): 89–106.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s: Contexts and Collaborations. Pinner: PLA; London: The British Library; Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

Cornhill Magazine, The. London: Smith, Elder, 1865.

Dorment, Richard, and Macdonald, Margaret F. James McNeill Whistler. London: Tate Gallery, 1994.

du Maurier, George. Peter Ibbetson. London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1892.

du Maurier, George. ‘The Illustrating of Books from the Serious Artist’s Point of View.’ The Magazine of Art (1890): 349–53; 371–75.

du Maurier, George. The Martian. Boston: Harper, 1898.

du Maurier, George.Trilby. London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1894.

Ellis, S. B. Memoirs and Services of the Late Sir S. B. Ellis. London: Saunders & Otley, 1866.

Garrison, Laurie. ‘The Seduction of Seeing in M.E. Braddon’s “Eleanor’s Victory” and the Evocative Publishing Context of Once a Week. ’ Victorian Literature and Culture 36 (2008): 111– 130.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: the Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; new ed. London: Lund Humphries, 2004.

Leighton, M. E., and Surridge, Lisa. ‘Sensation and Illustration.’ A Companion to Sensation Fiction. Ed. Pamela K. Gilbert. Oxford; Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 540–558.

Leighton, M. E., and Surridge, Lisa. ‘The Plot Thickens: Towards a Narratology of Illustrated Serial Fiction in the 1860s.’ Victorian Studies 51:1 (2008): 65–101.

Leighton, M. E., and Surridge, Lisa.‘The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly. ’ Victorian Periodical Review 42:3 (Fall 2009): 207–243.

[Lucas, Samuel]. ‘Illustrated Books.’ The Times. 24 January 1858: 10.

[Lucas, Samuel].‘More Gift Books.’ The Times. 2 January 1865: 12.

[Mansel, H. L.]. ‘Sensation Novels.’ The Quarterly Review 113 (1862): 481– 514.

‘Novelettes.’ The London Review of Politics, Society, Literature, Art, and Science (12 August 1865): 178.

Novels of Mystery from the Victorian Age. Ed. Maurice Richardson. London: Pilot Press, 1945.

Ormond, Leonée. George du Maurier. London: Routledge, 1968.

Ormond, Leonée . ‘George du Maurier, George Louis Palmella Busson (1834–1896)’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online ed., Oct 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9194]. Acessed 27 November 2011.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; rpt. New York: Dover, 1975.

Symons, Julian. Bloody Murder. 1972; rpt. London: Pan, 1992.

The Young George du Maurier: a Selection of His Letters. Ed. Daphne du Maurier. London: Peter Davis, 1951.

Wood, Ellen. East Lynne. 1861; Oxford: Oxford Classics, 2005.

Wynne, Deborah. The Sensation Novel and the Victorian Family Magazine. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001.

Last modified 9 June 2014