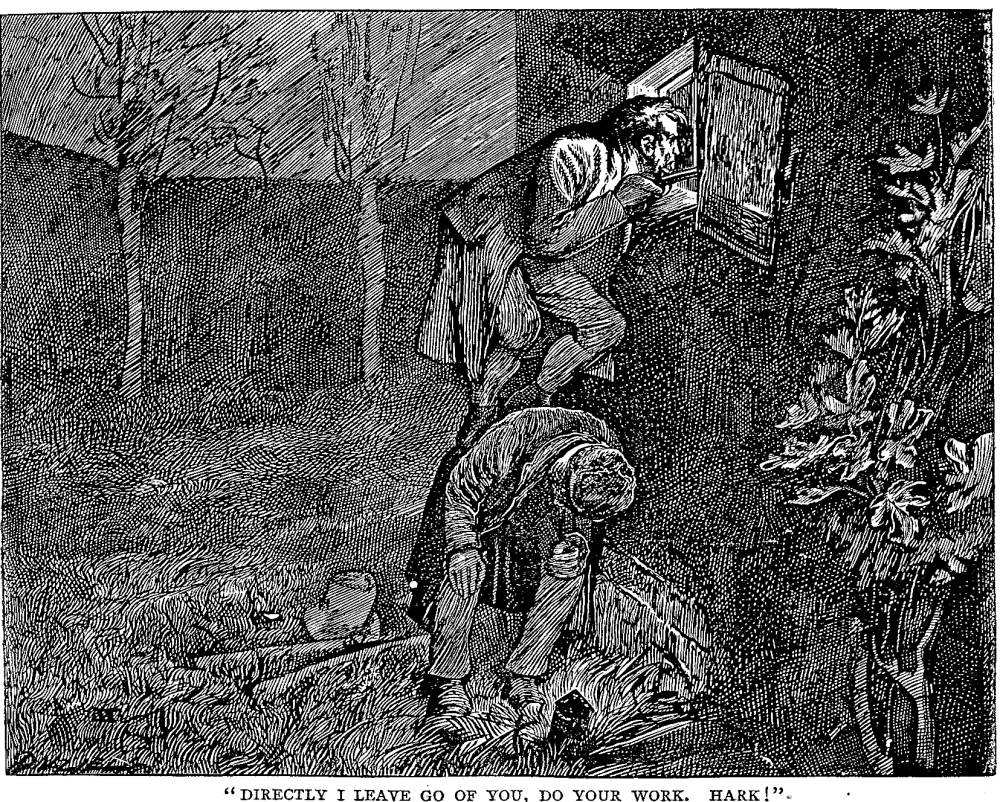

Original serial illustrator George Cruikshank's steel engraving

blends farce and melodrama effectively for an over-the-top

realisation of The Burglary (January 1838).

The episode of the botched burglary first appears in Part 10 (or chapter 22) of Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist, in the January 1838 edition of Bentley's Miscellany. It occurs when Bill Sikes tries to break into a house in the small town of Chertsey, in Surrey, with Toby Crackit as his accomplice, in order to effect a robbery. The ill-intentioned pair have brought Oliver along from Fagin's den of thieves in London, so that he can climb up and let them in through a small window on the ground floor.

For this original serialisation, Dickens had selected George Cruikshank (1792-1878) as his illustrator. Cruikshank duly realised the scene of the servants interrupting the robbery for the January instalment, implying that the venture will not meet with success. In fact, he could not yet have been aware either of the immediate consequences of the robbery, or the full outcome of it. The novelist himself in mid-March 1838 admitted to theatrical adapter and director Frederick Yates that he did not know what would happen to the principal characters: “I am quite satisfied that nobody can have heard what I mean to do with the different characters in the end, inasmuch as at present I don't quite know, myself” (Letters I: 388).

However, as it turns out, the episode is pivotal to the narrative. Dickens's original readers would soon realise that, by sheer coincidence or through the machinations of Providence, the substantial house that Sikes has selected as his target belongs to the Maylies, the wealthy family who adopted Rose, the sister of Agnes, Oliver's mother.

For the 1846 Chapman and Hall re-release of the novel in volume form, Cruikshank elected — undoubtedly with Dickens's approval — to make the celebrated workhouse scene Oliver's Asking for More (from Part 1, February 1837) the frontispiece. But when it came to the monthly wrapper containing eleven scenes from the novel for the 1846 periodical "re-serialization," Cruikshank included in the design's upper left-hand corner Sikes at the window on the outside of the house, gesticulating as if telling Oliver how to open the door for him and Toby, once the boy has descended to the floor. By its prominence in the wrapper, Cruikshank is now implying that the incident is significant in Oliver's "progress." By this time, then, Cruikshank seems to have realised that the foiled robbery is a crucial event in the downward fortunes of Fagin, Sikes, and, of course, Nancy — and a much happier reversal of Oliver's fortunes.

There is more in these illustrations than first meets the eye. By injecting the notorious housebreaker into the scene in a framed portrait, Cruikshank implies that he is an onlooker, unable to act, simply watching the unfolding drama with interest and some frustration. The critic Anthony Burton notes how throughout the sequence the artist employs doors and windows as "potent symbols of exclusion and inclusion" (127), with Sikes obviously excluded from the action here, but Oliver wounded by the men who confront the intruder: "the door opens on him and emits a puff of smoke and a bullet" (127).

Cruikshank was only the first of the novel's illustrators. In his 1865 frontispiece, the American illustrator Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1822-1888), knowing full well the outcome not merely of the robbery but of the entire story, suggests more clearly in his caption, "The Attempted Burglary" [emphasis added], that cracksman Toby Crackit and housebreaker Bill Sikes will not succeed. Since the novel circulated in the United States through both legitimate and pirated editions, as well as in adaptations upon the popular stage, Darley would already have known that the Chertsey burglary is a turning-point in the plot. Certainly he seems to have reflected this understanding in his choice of topic for the second frontispiece for the volume, which contains the second half of the twenty-four chapters. Darley ignores the workhouse segment of the story entirely in both these 1865 frontispieces. In the first he focuses on Oliver's relationship with Fagin; in the second, he depicts the protagonist with Sikes in this very (botched burglary) episode. Here, as in his 1888 series of Character Sketches from Dickens, Darley depicts Sikes as a sordid, lower-class villain out of contemporary melodrama. Yet his Sikes is much more of an individual, despite his characteristic long face and white top hat, derived directly from Cruikshank. He has something about him of the relentless realism of another British illustrator James Mahoney (1810-1879). Mahoney depicts Sikes in his 1871 volume leading off the Household Edition as more an individual than a type, although here the focus of the burglary illustration is Oliver himself rather than Sikes.

American illustrator Darley's photogravure in which the gang experience difficulties even before they have Oliver climb into the house: The Attempted Burglary (1865).

Since the second volume of the Sheldon & Company (New York) American Household Edition of The Adventures of Oliver Twist begins with Chapter 29, and "Has an Introductory Account of the Inmates of the House, to which Oliver resorted," the incident which Darley has depicted in the frontispiece lies not ahead of Dickens's readers, but immediately behind them in the narrative. They would most likely have responded to the Darley frontispiece analeptically, perhaps even re-reading the account of events leading up to the break-in at the end of the first volume to match the determined look on the face of Sikes and the pathetic look on the face of Oliver "stupified by the unwonted exercise, and the drink which had been forced upon him. . . ." In the text, the glare of Sikes's partially open dark lantern falls intensely on Oliver's face, and so it does here in the Darley illustration, although Sikes has yet to hoist Oliver up by his collar "with his feet first."

British illustrator's Harry Furniss's lithograph of the chaotic scene

which presents the robbery with

tremendous vigour: The

Burglary (1910).

With a knowledge of the British programs of illustration that preceded his, the slightly later illustrator, Harry Furniss (1854-1925), has yet another take on this important episode. He provides a much more dynamic composition in which the focus is not the robbers but the four servants who burst into the storeroom just as Oliver is about to pass out of it. A dark plate in the manner of Phiz, Darley and Mahoney does not permit the reader to see much of the action, just the outlines of the characters, as they depict the low-key scene immediately preceding the melodramatic confrontation of housebreakers and armed servants in the storeroom. It has some advantages. In particular, Darley's highlighting of the blond-haired Oliver in the darkness helps to underscore his innocence, and obvious reluctance to participate in the nocturnal crime. But Furniss's scene is both clear and memorable. Seeing the illustration before reading the accompanying text, readers might expect the worst, but by the time the curtain closes Sikes has at least abstracted Oliver from the immediate danger posed by these servants. After this crucial turning-point, a much more lasting rescue will be effected.

Relevant Illustrations from the Household and Charles Dickens Library Editions

Left: James Mahoney's 1871 wood-engraving of Sikes's dragging an unwilling Oliver to the site of the burglary at Chertsey in Surrey, in Sikes, with Oliver's hand still in his, softly approached the low porch. Right: Harry Furniss depicts Oliver as an unwilling accomplice in Oliver in the Grip of Sikes (1910).

As mentioned above, the novel circulated in the United States in various forms, so Darley would have known by the early 1860s that the burglary came at a pivotal juncture in the lost-heir plot — after all, this dramtic episode at Chertsey leads to ennobling Nancy and to Oliver's ceasing to be a dynamic character. Hence no doubt his decision to feature it later on in the second frontispiece for the two-part novel.

In the 1871 Mahoney illustration of the gang clambering into brewery, the burly figure of Sikes (stepping on the back of his confederate, Toby Crackit, centre) leans into the storeroom window, pointing a loaded pistol at his reluctant charge, whom he has already dropped into the house through the little lattice window, about five-and-a-half feet from the ground. The reader (perhaps recalling the original Cruikshank illustration, either from the serial or the 1846 revised edition) must visualize Oliver's reaction to Sikes's threat and the directions of Toby Crackit. He is already looking for the passageway leading to the door which he is to open for the burglars. In this way, Mahoney emphasizes the young hero's desperate and bewildering situation. The boy's utter helplessness and vulnerability are equally apparent in Furniss's powerful depiction of Oliver in the Grip of Sikes.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that another British illustrator, Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke, 1857-1937) produced coloured lithographs at the turn of the century which bespeak a certain fascination with the uncouth, atavistic villain of Dickens's Newgate novel, but make no particular reference to the Chertsey robbery.

Related Material

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

- George Cruikshank's Serial Illustrations for Dickens's Adventures of Oliver Twist (February 1837 through April 1839)

- Nancy and Bill Sikes in various editions of Oliver Twist (1837-1910))

- Early dramatic adaptations of Oliver Twist (1838-1842)

- Alternative Dickens: cartoon based on Cruikshank in Oliver Twist

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Bolton, Philip H. Dickens Dramatized. Boston, Mass., and London: G. K. Hall and Mansell, 1987.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974. Pp. 93-128.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1861. 2 vols.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_______. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey and Kathleen Tillotson. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. 1 (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3.

Kyd. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

Created 3 January 2022