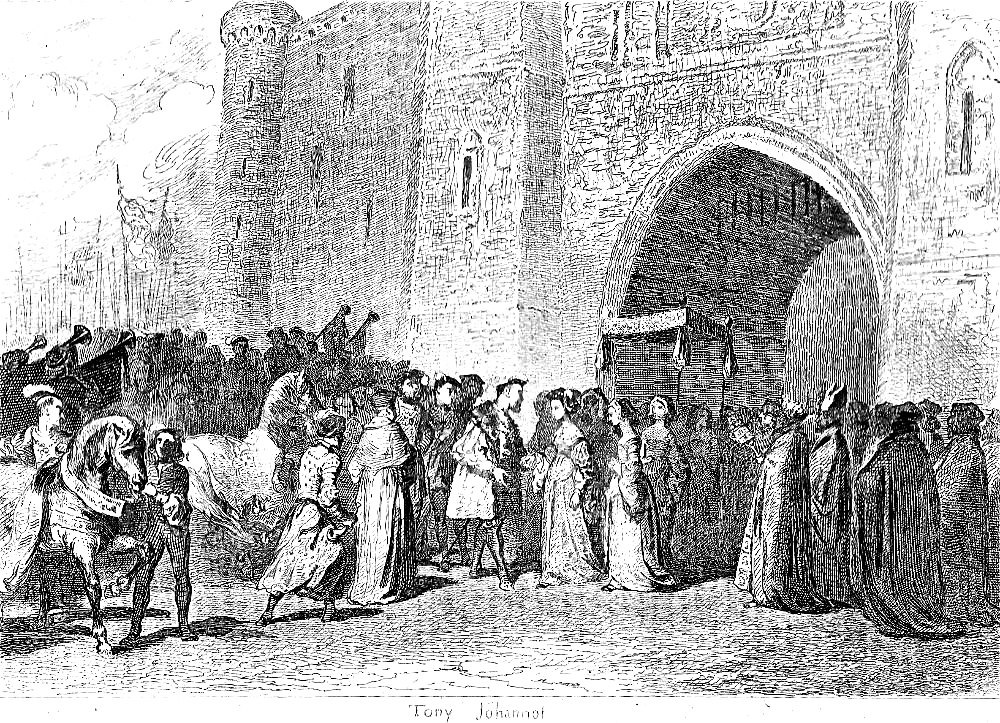

The Meeting of Henry the Eighth and Anne Boleyn by French illustrator Tony Johannot for the second instalment of Windsor Castle. An Historical Romance for August 1842 in Ainsworth's Magazine, which he founded he had quarrelled with the publisher and left his editorial post at Bentley's Miscellany. "Book the First: Anne Boleyn," Chapter III, "Of the Grand Procession to Windsor Castle — Of the Meeting of King Henry the Eighth and Anne Boleyn at the Lower Gate — Of their Entrance into the Castle — And how the Butcher was Hanged from the Curfew Tower," facing p. 29. 9.5 cm high by 13.8 wide, framed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: The Arrival of Anne Boleyn at Windsor Castle

Leaving the barge and its occupants to await the king's arrival, the cavalcade ascended Thames Street, and were welcomed everywhere with acclamations and rejoicing. Bryan Bowntance, who had stationed himself on the right of the arch in front of his house, attempted to address Anne Boleyn, but could not bring forth a word. His failure, however, was more successful than his speech might have been, inasmuch as it excited abundance of merriment.

Arrived at the area in front of the lower gateway, Anne Boleyn's litter was drawn up in the midst of it, and the whole of the cavalcade grouping around her, presented a magnificent sight to the archers and arquebusiers stationed on the towers and walls.

Just at this moment a signal gun was heard from Datchet Bridge, announcing that the king had reached it, and the Dukes of Suffolk, Norfolk, and Richmond, together with the Earl of Surrey, Sir Thomas Wyat, and a few of their gentle men, rode back to meet him. They had scarcely, however, reached the foot of the hill when the royal party appeared in view, for the king with his characteristic impatience, on drawing near the castle, had urged his attendants quickly forward.

First came half a dozen trumpeters, with silken bandrols fluttering in the breeze, blowing loud flourishes. Then a party of halberdiers, whose leaders had pennons streaming from the tops of their tall pikes. Next came two gentlemen ushers bareheaded, but mounted and richly habited, belonging to the Cardinal of York, who cried out as they pressed forward, "On before, my masters, on before!—make way for my lord's grace."

Then came a sergeant-of-arms bearing a great mace of silver, and two gentlemen carrying each a pillar of silver. Next rode a gentleman carrying the cardinal's hat, and after him came Wolsey himself, mounted on a mule trapped in crimson velvet, with a saddle covered with the same stuff, and gilt stirrups. His large person was arrayed in robes of the finest crimson satin engrained, and a silk cap of the same colour contrasted by its brightness with the pale purple tint of his sullen, morose, and bloated features. The cardinal took no notice of the clamour around him, but now and then, when an expression of dislike was uttered against him, for he had already begun to be unpopular with the people, he would raise his eyes and direct a withering glance at the hardy speaker. But these expressions were few, for, though tottering, Wolsey was yet too formidable to be insulted with impunity. On either side of him were two mounted attend ants, each caring a gilt poleaxe, who, if he had given the word, would have instantly chastised the insolence of the bystanders, while behind him rode his two cross-bearers upon homes trapped in scarlet.

Wolsey's princely retinue was followed by a litter of crimson velvet, in which lay the Pope's legate, Cardinal Campeggio, whose infirmities were so great that he could not move without assistance. Campeggio was likewise attended by a numerous train.

After a long line of lords, knights, and esquires, came Henry the Eighth. He was apparelled in a robe of crimson velvet furred with ermines, and wore a doublet of raised gold, the placard of which was embroidered with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, large pearls, and other precious stones. About his neck was a baldric of balas rubies, and over his robe he wore the collar of the Order of the Garter. His horse, a charger of the largest size, and well able to sustain his vast weight, was trapped in crimson velvet, purfled with ermines. His knights and esquires were clothed in purple velvet, and his henchmen in scarlet tunics of the same make as those worn by the warders of the Tower at the present day.

Henry was in his thirty-eighth year, and though somewhat overgrown and heavy, had lost none of his activity, and but little of the grace of his noble proportions. His size and breadth of limb were well displayed in his magnificent habiliment. His countenance was handsome and manly, with a certain broad burly look, thoroughly English in its character, which won him much admiration from his subjects; and though it might be objected that the eyes were too small, and the mouth somewhat too diminutive, it could not be denied that the general expression of the face was kingly in the extreme. A prince of a more "royal presence" than Henry the Eighth was never seen, and though he had many and grave faults, want of dignity was not amongst the number.

Henry entered Windsor amid the acclamations of the spectators, the fanfares of trumpeters, and the roar of ordnance from the castle walls.

Meanwhile, Anne Boleyn, having descended from her litter, which passed through the gate into the lower ward, stood with her ladies beneath the canopy awaiting his arrival.

A wide clear space was preserved before her, into which, however, Wolsey penetrated, and, dismounting, placed himself so that he could witness the meeting between her and the king. Behind him stood the jester, Will Sommers, who was equally curious with himself. The litter of Cardinal Campeggio passed through the gateway and proceeded to the lodgings reserved for his eminence.

Scarcely had Wolsey taken up his station than Henry rode up, and, alighting, consigned his horse to a page, and, followed by the Duke of Richmond and the Earl of Surrey, advanced towards Anne Boleyn, who immediately stepped forward to meet him.

"Fair mistress," he said, taking her hand, and regarding her with a look of passionate devotion, "I welcome you to this my castle of Windsor, and trust soon to make you as absolute mistress of it as I am lord and master." ["Book the First: Anne Boleyn," Chapter III, "Of the Grand Procession to Windsor Castle — Of the Meeting of King Henry the Eighth and Anne Boleyn at the Lower Gate — Of their Entrance into the Castle — And how the Butcher was Hanged from the Curfew Tower," pp. 27-29]

The Four Illustrations of Tony Johannot

When Ainsworth broke with Bentley in 1841, he dashed over to Paris to enlist the French artist Tony Johannot, illuminator of Moliére, Scott, and other famous authors, as his illustrator for a historica; novel about Henry VIII, Windsor Castle, which Ainsworth intended to release in monthly parts commencing April 1842. Butb two weeks before the first number was scheduled, Ainsworth's mother died; his grief piled on top of the heavy burdens of owning and editing and writing for his magazine temporarily overwhelmed him. A typically unsubtle publicity campaign had already been instituted in the March Ainsworth's: right under the line cut of Cruikshank and Ainsworth planning their novel, the author ran a fulsomely enthusiastic notice of Johannot which claimed that his illustrations to Don Quixote and other classics were the finest ever produced. That may not have been particularly agreeable to George. [Patten, pp. 172-173]

Antoine Johannot, otherwise known as Tony Johannot (1803-52), was descended from French Hugenots who had settled in Offenbach am Main after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Johannot was a painter turned lithographer, having learned the art of engraving from his brothers Alfred and Charles. He collaborated with Alfred on the illustrations for the novels of James Fenimore Cooper and Sir Walter Scott. Although he initially preferred wood engraving, in the mid-1840s he resumed etching. He may have come to Ainsworth's attention through his book illustrations or through his exhibiting historical canvasses at the Paris Salon from 1831 onward. The impressionist style that Johannot employed in the first four illustrations for Windsor Castle. An Historical Romance were not at all like the detailed and vigorous steel-engravings of Ainsworth's former illustrator, George Cruikshank, which were evidently more to the novelist's taste. Robert L. Patten, indeed, is probably correct about Ainsworth's cool reaction to Johannot's "rather vaguely delineated" scenes (II: 173) that failed to provide the kind of dramatic tension he required to complement his prose on the one hand and the tranquil nature studies and elegant architectural sketches of Sandhurst drawing-master W. Alfred Delamotte on the other.

Although Cruikshank took over from Tony Johannot after just four instalments, Ainsworth must generally have been satisfied with the French historical painter's epic canvas that introduces readers to the principal characters except Herne the Hunter and the chief setting, Windsor Castle. The presence of Cardinal Wolsey (just left of centre) and the mention of Cardinal Campeggio's litter, which has already passed into the courtyard, prepare the reader for the first movement of the novel, the King's divorcing Catherine of Arragon in order to marry the Lady Anne Boleyn. However, these crucial figures are lost in the epic pageantry, and Anne is not particularly distinguished. If Henry has already surrendered to Anne's wiles, as George Worth suggests, her depiction is curiously lacking in both energy and beauty.

Rather than endeavouring, as Jahonnot has done here, to synthesize several pages of description, Cruikshank would probably have focussed on the key figures, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and minimized the cavalcade, with the exception of Will Sommers. The king's rather knowing jester would have held a certain fascination for Cruikshank, who had gravitated towards such comic characters as Xit in The Tower of London. Cruikshank would probably have attempted to realise not merely Ainsworth's detailed descriptions of the characters' sumptuous clothing, but also their distinctive characteristics: Henry's masculinity and pomposity, Anne's deviousness and beauty, and Will's combination of "drollery and oddity of manner" (23). Johannot suggests neither the Tudor monarch's impetuosity nor his vindictiveness, qualities which Ainsworth dramatises in this chapter.

Although Cruikshank was occasionally fallible in his choices of subject matter and his execution, he would not likely have had the trumpets (left of centre) blowing as Henry attempts to engage Anne in conversation. He would also have shown the entrance-way, portcullis, and brickwork in sharper focus. Moreover, the moment chosen by the French illustrator would not have been sufficiently dramatic for Cruikshank, who would have taken greater interest in Henry's observing the butcher's execution on the battlements of the Curfew Tower, or the butcher's predicting that one day Anne Boleyn will find herself pleading in vain for her life. In other words, although Johannot's crowd scene is suitably epic, it lacks the kind of sharp focus that one sees in such historical canvasses from Cruikshank's sequence in The Tower of London as Sir Thomas Wyat dictating terms to Queen Mary in the Council.

References

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Jack Sheppard. A Romance. With 28 illustrations by George Cruikshank. In three volumes. London: Richard Bentley, 1839.

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Windsor Castle. An Historical Romance. Illustrated by George Cruikshank and Tony Johannot. With designs on wood by W. Alfred Delamotte. London: Routledge, 1880. Based on the Henry Colburn edition of 1844.

Patten, Robert L. Chapter 30, "The 'Hoc' Goes Down." George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, vol. 2: 1835-1878. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers U. P., 1991; London: The Lutterworth Press, 1996. Pp. 153-186.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Last modified 27 November 2017