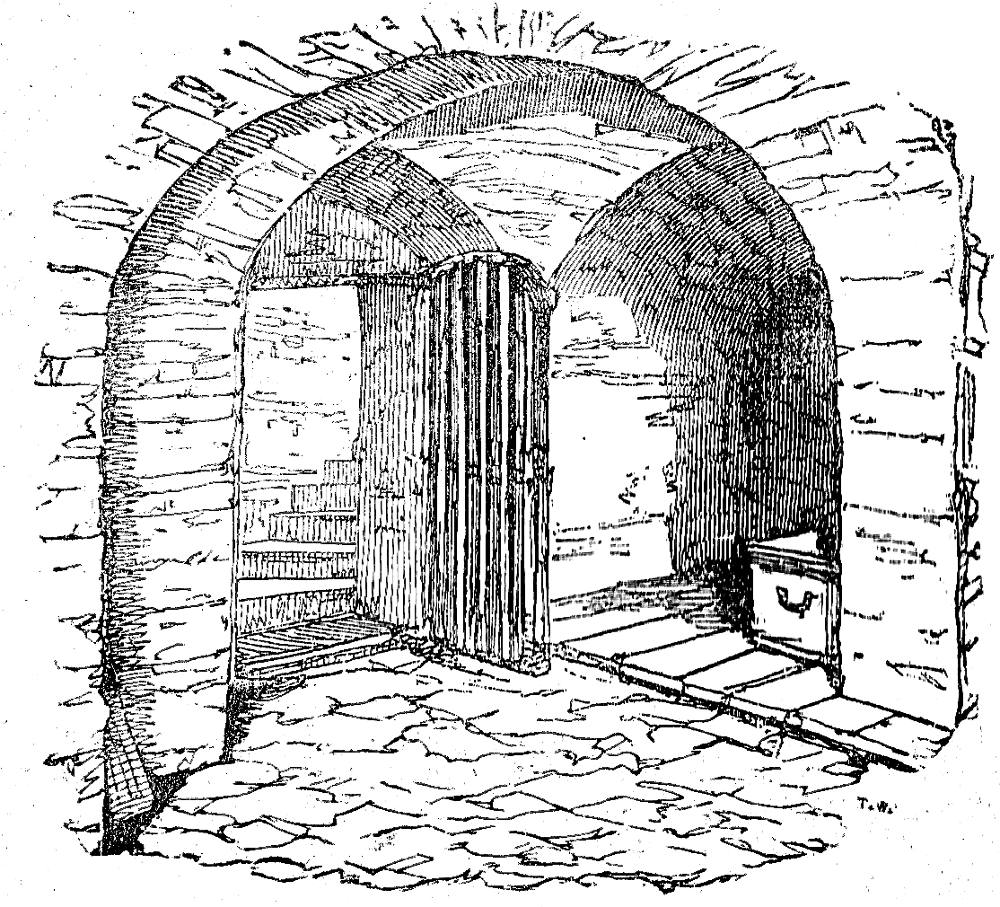

Basement Chamber in the Flint Tower — George Cruikshank. Final, double-number, December 1840. Ninety-first illustration and fifty-fourth wood-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XXXVIII, positioned as the headpiece for Chapter XXXVII. 8.4 cm high x 9.1 wide, vignetted, top of p. 385: running head, "The Martin Tower." Although Mary agrees with Elizabeth's assessment of the flimsy evidence that Renard has engineered in order to assure the execution of Mary's half-sister, Mary is having difficulty deciding what to do with her ex-lover, presently housed in the spartan quarters of the Flint Tower. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Complemented

Elizabeth still continued a close prisoner in the Bell Tower. But she indulged the most sanguine expectations of a speedy release. Her affections had received a severe blow in Courtenay's relinquishment of his pretensions to her hand, and it required all her pride and mastery over herself to bear up against it. She did, however, succeed in conquering her feelings, and with her usual impetuosity, began now to hate him in the proportion of her former love. While his mistress was thus brooding over the past, and trying to regulate her conduct for the future within the narrow walls of her prison, Courtenay, who had been removed to the Flint Tower, where he was confined in the basement chamber, was likewise occupied in revolving his brief and troubled career. A captive from his youth, he had enjoyed a few months' liberty, during which, visions of glory, power, greatness, and love—such as have seldom visited the most exalted— opened upon him. The bright dream was now ended, and he was once more a captive. Slight as his experience had been, he was sickened of the intrigues and hollowness of court life, and sighed for freedom and retirement. Elizabeth still retained absolute possession of his heart, but he feared to espouse her, because he was firmly persuaded that her haughty and ambitious character would involve him in perpetual troubles. Cost what it might, he determined to resign her hand as his sole hope of future tranquillity. In this resolution he was confirmed by Gardiner, who visited him in secret, and counselled him as to the best course to pursue.

"If you claim my promise," observed the crafty chancellor, "I will fulfil it, and procure you the hand of the princess, but I warn you you will not hold it long. Another rebellion will follow, in which you and Elizabeth will infallibly be mixed up, and then nothing will save you from the block." [Ch. XXXVIII. —How the Princess Elizabeth and Courtenay were delivered out of the Towerto further durance; andhow Queen Mary was wedded, by proxy, to Philip of Spain," pp. 396-97]

Commentary: Tidying up loose ends of the various plots

Strangely enough, Cruikshank and Ainsworth have chosen not realise the scene in which Queen Mary sends her half-sister, Elizabeth, and her former lover, Courtenay, away from court. The illustration of the Lady Jane Grey's accommodation (a comfortably furnished parlour in the basement of the Jewel Tower) circa 1840 contrasts the cramped, windowless quarters in which Mary has caused Courtenay, recaptured during the rebellion, to be housed. Although the picture of the unadorned basement chamber on page 385 occurs at the head of Chapter 37, Cruikshank apparently intends it to set the scene for the release of Courtenay and Elizabeth, who has been incarcerated in the cramped quarters of the Bell Tower. Mary's failure to order the executions of Elizabeth and Courtenay thoroughly disappoints Renard, who had hoped to persuade Mary to have the pair beheaded at the same time as Lord Guildford Dudley and his wife, Lady Jane Grey.

The Spanish ambassador has, in fact, just finished telling the Holy Roman Emperor's legate, the Count D'Egmont, "My hour of triumph is at hand" (399), for he had been certain that Mary would order the executions of Elizabeth and Courtenay for treason and sedition. He is mortified, therefore, when Mary agrees with her half-sister that "their guilt [has] not [been] clearly proven" (393). Rather, Mary orders that Elizabeth be exiled to the Palace of Woodstock, Oxfordshire, under the watchful (but essentially benign) eye of Sir Henry Bedingfeld. Although she likewise consigns Courtenay to Fotheringay Castle in Northamptonshire, the rash young noble in fact will go into exile in Italy, where he will die unexpectedly two years later at Padua. Chagrined that Mary has not heeded his advice and that his designs for a Catholic purge of English Protestants have been frustrated, Renard resignshis post as Mary's political and foreign-policy advisor, "unable to repress hischoler" (400). He now retires not just from the English court but also from thepages of the novel "covered with shame and confusion" (400), but much to the nineteenth-century English reader's satisfaction. The melodrama, then, has concluded with the survival of Elizabeth and the triumph of Cuthbert Cholmondeley, as well as the painful death of Nightgall and the ignominious departure of Renard. The character comedy will shortly conclude with the marriage of Xit ("Sir Narcissus Le Grand," as he now styles himself) and Jane, Queen Mary's fool. The tragic strain of the novel will be resolved by the execution of the blameless, devout, but rather naive Lady Jane Grey.

The setting is the basement room of a tower on the north battlements which in 1238 Henry III ordered constructed as part of a new, defensive curtain wall. Henry strengthened this second line of defencewith a number of new towers, including the Flint Tower, which is connected to the Bowyer Tower by a walkway. Historically, the Flint Tower was used as a place of safekeeping during times of threat, as in the aftermath of the robbery at Westminster Abbey in 1303.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. Accessed 11 September 2017. https://ainsworthandfriends.wordpress.com/2013/01/16/william-harrison-ainsworth-the-life-and-adventures-of-the-lancashire-novelist/

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Jerrold, Blanchard. The Life of George Cruikshank. In Two Epochs. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus, 1882.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 2 November 2017