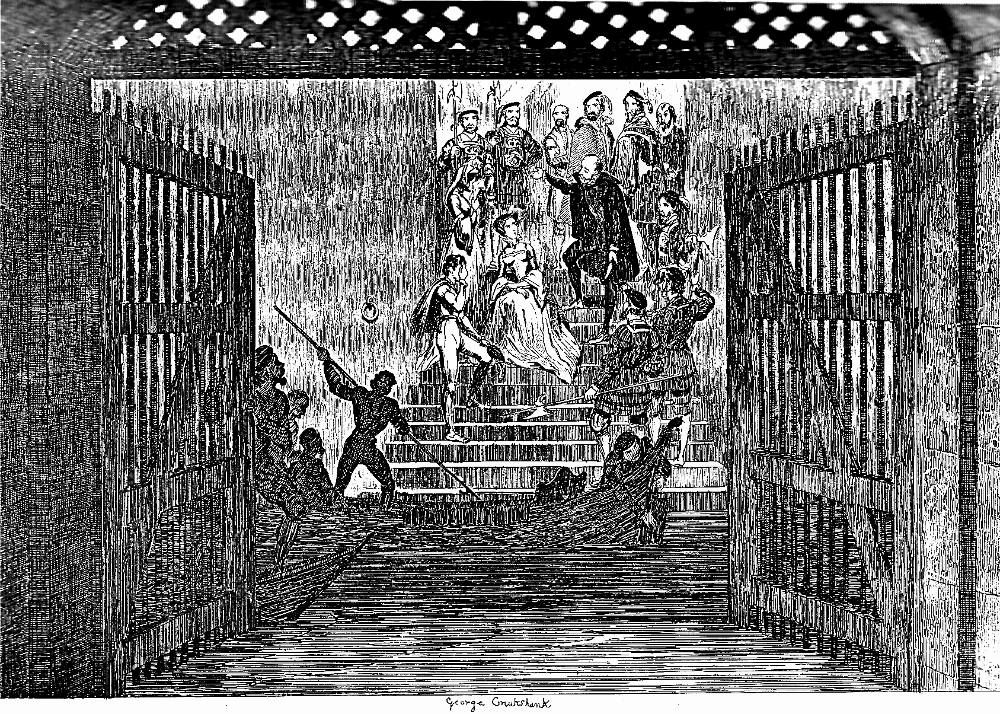

Elizabeth brought Prisoner to the Tower. — George Cruikshank. Eleventh instalment, November 1840 number. Eightieth illustration and thirty-fourth steel-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XXXII. 10 cm high x 14.4 wide, framed, facing p. 346: running head, "Elizabeth Brought Prisoner to the Tower." The scene affords Cruikshank the opportunity to provide yet another perspective of the Water or Traitor's Gate, and to contrast the attitudes of his female leads: Princess Elizabeth, Queen Mary, and Lady Jane Grey. Since Cruikshank has juxtaposed this plate with that in which, in a spirit of self-sacrifice, Jane, having escaped, now offers herself as a prisoner as she begs for her husband's life, the illustrator is consciously foiling the two Protestant princesses in back-to-back steel-engravings. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"Will it please you to take my cloak as a protection against the rain?" said Bedingfeld, offering it to her. But she pushed it aside "with a good dash," as old Fox relates; and springing on the steps, cried in a loud voice, "Here lands as true a subject, being prisoner, as ever set foot on these stairs. And before thee, O God, I speak it, having no other friend but thee."

"Your highness is unjust," replied Bedingfeld, who stood bare-headed beside her; "you have many friends, and amongst them none more zealous than myself. And if I counsel you to place some restraint upon your conduct, it is because I am afraid it may be disadvantageous reported to the queen."

"Say what you please of me, sir," replied Elizabeth; "I will not be told how I am to act by you, or any one."

"At least move forward, madam," implored Bedingfeld; “you will be drenched to the skin if you tarry here longer, and will fearfully increase your fever."

"What matters it if I do?" replied Elizabeth, seating herself on the damp step, while the shower descended in torrents upon her. "I will move forward at my own pleasure — not at your bidding. And let us see whether you will dare to use force towards me."

"Nay, madam, if you forget yourself, I will not forget what is due to your father's daughter," replied Bedingfeld, "you shall have ample time for reflection."

The deeply-commiserating and almost paternal tone in which this reproof was delivered touched the princess sensibly; and glancing round, she was further moved by the mournful looks of her attendants, many of whom were deeply affected, and wept audibly. As soon as her better feelings conquered, she immediately yielded to them; and, presenting her hand to the old knight, said, "You are right, and I am wrong, Bedingfeld. Take me to my dungeon."[Chapter XXXII. — "How the Princess Elizabeth was brought a Prisoner to the Tower," page 346.]

Commentary

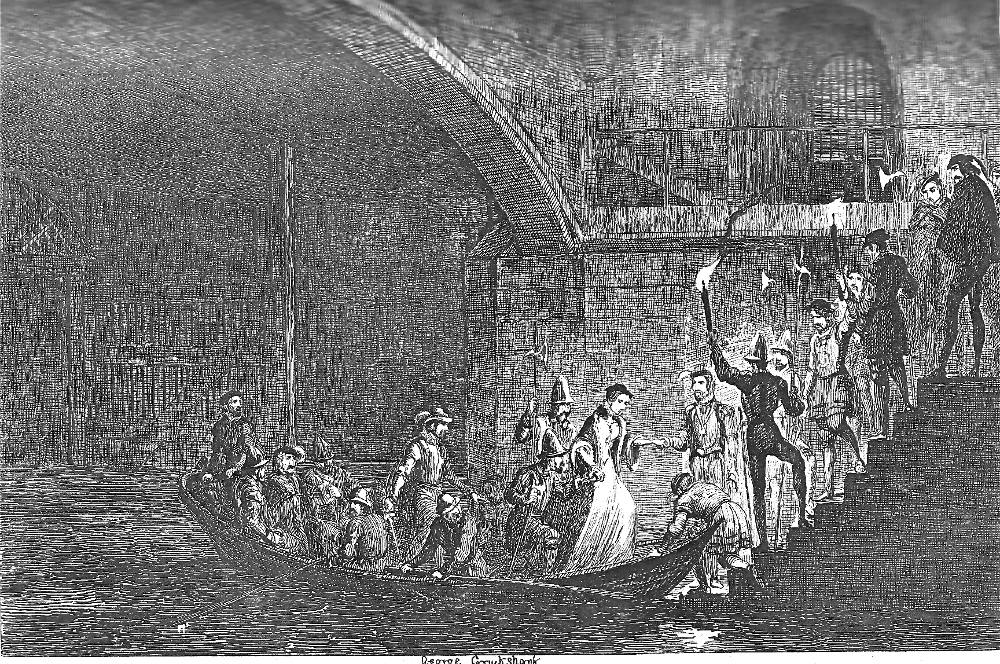

By virtue of both the subject and the characters involved, Cruikshank is inviting readers to compare Lady Jane Grey's return to the Tower of London through Traitor's Gate at the close of Book the First in Jane Grey and Lord Gilbert Dudley brought back to the Tower through Traitors' Gate (Chapter 17: fourth monthly instalment). Whereas Jane was tranquil and even passive, as if resigned to her fate, Elizabeth is self-assertive and dynamic as she chafes against Mary's characterizing her as a traitor. The Lord Lieutenant of the Tower is suitably diplomatic, realising that Elizabeth may yet be Queen herself. Jane, Cruikshank seems to imply, may easily lose her balance and fall into the murky waters of the moat (a metaphor for her politically precarious position as one of the chief Protestant claimants to the throne in an England now governed by a Catholic revivalist), and must be watched, guarded, and assisted — a subject of constant surveillance. Elizabeth, on the other hand, though brought to the Tower under similar circumstances, lacks the encumbrance of an inconveniently rash, ambitious husband; she is, moreover, entirely blameless as she has scrupulously avoided even communicating with the leaders of the recent insurgency, Sir Thomas Wyat and Lord Guildford Dudley, and has been far from the centre of power and the county of the rebellion. But, more apparent than her aloofness in the accompanying text is her cunning political strategizing: she knows that she can assert her innocence, and that her half-sister will be reluctant to order her execution without substantial evidence of treason. Therefore, Elizabeth can afford to be combative with Sir Henry Bedingfeld and her security detail, and reject any sort of patronizing assistance: she is the self-assured heir of Henry VIII, and, with Jane despatched on Tower Green, will become the leading Protestant claimant.

Thus, Cruikshank has replaced the orderly, low-key procession up the steps from the water in the earlier illustration with Elizabeth, in the centre on the same staircase, apparently going down rather than up as she truculently seats herself, much to the surprise of the dozen guards and courtiers surrounding her. Cruikshank challenges the viewer who has yet to read the accompanying text to determine whether those sturdy wooden gates are opening or closing upon the Princess Elizabeth, whose political instincts have thus far ensured her survival and may yet facilitate her ascent to the throne.

Earlier Depictions of the Water or Traitors' Gate

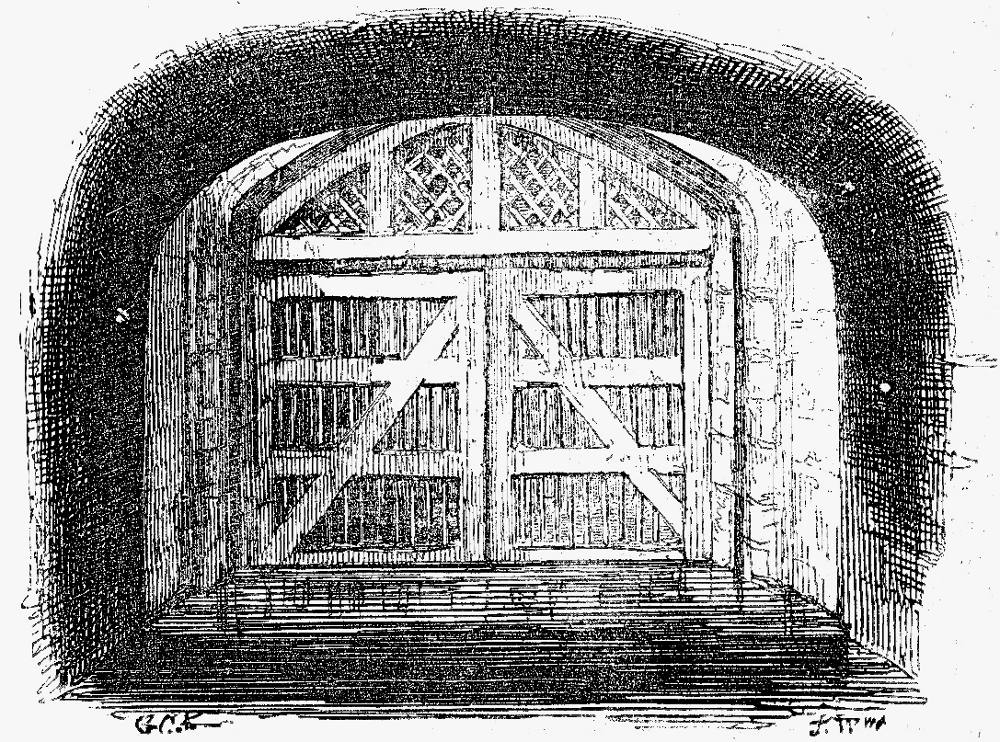

Above: The present-day tranquility of Cruikshank's earlier wood-engraving contrasts the high drama of the historical canvas featuring Jane and Lord Guildford Dudley enter the Tower's precincts as captives: The Traitor's Gate (February 1840). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: The gloomy dark plate in which Jane, no longer Queen, returns to the prison-fortress, Jane Grey and Lord Gilbert Dudley brought back to the Tower through Traitors' Gate (April 1840). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Blanchard Jerrold on these Rembrandt-like scenes

Blanchard Jerrold, Cruikshank's first biographer, recalls the relationship of the illustrator and Ainsworth during their collaboration, and extols Cruikshank's historical canvasses in The Tower of London:

On the retirement of Ainsworth from Bentley's Miscellany, business relations were resumed between himself and the artist; and Cruikshank was advertised as illustrator of Ainsworth's Magazine. And at this point Cruikshank passed from his humorous to his more ambitious and higher phase.

The Tower of London appears to have made a strong effect on Cruikshank's mind. In the Omnibushe drew some curious bits of observation of the wreck of that part of the Tower which the fire had attacked, and in his illustrations to Ainsworth's story he manifested a desire to express the historical power as an artist that was in him. He composed pictures free from exaggeration, and grand and impressive both in conception and treatment. Having substituted steel plates for copper, he felt that he was upon more lasting work, and he laboured hard to produce pictures of the highest finish. He was right: some of the finest work he has left lies between Ainsworth's pages, and indicates a range of power in the artist which he was never destined to prove fully. The fates had been against him in early life; and he was, although even much later he could not bring his eager and intrepid mind to admit it, too old to take his seat in an academy, and get through the drudgery, without which not even the most bountifully gifted artist can do himself justice. In these Rembrandt-like scenes in the Tower, he taught the world that his idea that he was a great historical painter who had lost his way, was no wild and vain fancy.[Blanchard Jerrold, Chapter 9, "Illustrations to Harrison Ainsworth's Romances"]

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Jerrold, Blanchard. The Life of George Cruikshank. In Two Epochs. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus, 1882.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 29 October 2017