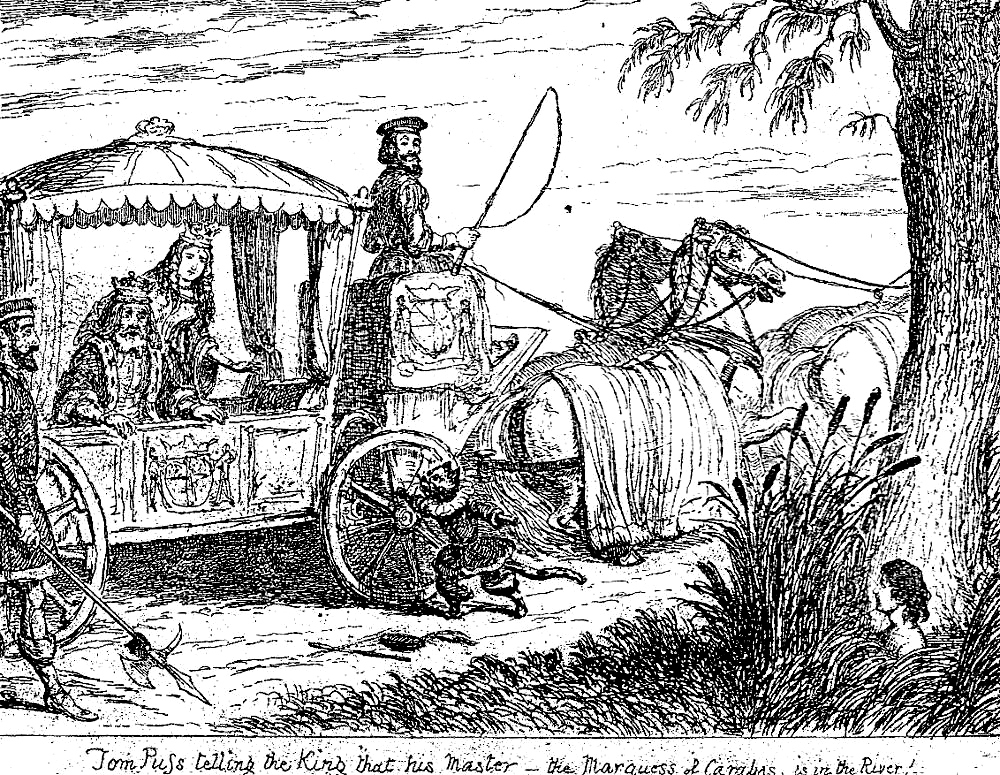

Tom Puss, after his Master is dressed, introduces him to the King as the Marquess of Carabas (7.2 cm high by 9.7 cm wide, exclusive of caption, framed, facing page 12) — the fifth illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1864 and for the fourth and final tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. Tom Puss now introduces his "master, The Marquis of Carabas," to the King and Princess in the Royal State Carriage. In his new suit, Caraba looks like a courtier in the Renaissance, with hose, puffed sleeves at the shoulder, and a short velvet cloak; in deference to the royal couple, Caraba has doffed his feather cap. The open carriage door implies that the king has just invited the lad to ride with him through his estates to the castle (in fact, still very much occupied by the usurping ogre at this point).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Passage Illustrated

Puss stopped these [foot-]men and told them that whilst his master, the Marquis of Carabas, was bathing in the river some one had taken away his clothes, and that he wished to tell the king of it. The foot-men [seen on either side of the carriage in the Cruikshank illustration] told this to the guards [to the rear of the carriage], the King was informed of it, and the carriage stopped. Puss then came forward and told his majesty that a most extraordinary thing had happened, which was, that whilst his master was bathing, some sly thief had taken away his clothes, and that he was now close by in the river, and could not, of course, present himself to his majesty until he had got another suit of clothes. "Well," said the King, "it is an extraordinary circumstance, and what is very curious and most fortunate, I have brought several new suits of clothes with me intending to present a suit to the Marquis in return for his very nice presents of the rabbits," The king then ordered his servants to get the box of clothes out of the "boot" of the carriage, and then ordered the coachman so drive about for a short time so as to give the Marquis an opportunity of dressing himself, which he was not long in doing, after the carriage left. (Tom had taken care to provide towels for his master.)

The Marquis — for so we may call him as far as appearances went, for when dressed in one of these Court dresses, he looked very handsome, and had all the appearance of a noble prince — when the carriage returned, Puss, acting the part of a chamberlain, introduced his master to the King and the Princess, who seemed pleased to make his acquaintance, and the King invited him into the carriage and introduced him to his daughter, who smiled most graciously, and also seemed much pleased. But if the king and the princess were pleased with the appearance of Caraba, they were still more pleased, nay, delighted, by his manner and his sensible and manly observations about the weather, the state of the crops, and so on. The king adverted to the extraordinary circumstance of the marquis having a Tom cat for a gamekeeper. Caraba admitted that it was so, but said that he had found him to be a faithful and most invaluable servant. — George Cruikshank, "Puss in Boots," pp. 12-13.

The Context in Perrault

The king immediately commanded the officers of his wardrobe to run and fetch one of his best suits for the Lord Marquis of Carabas.

The king received him very courteously. And, because the king's fine clothes gave him a striking appearance (for he was very handsome and well proportioned), the king's daughter took a secret inclination to him. The Marquis of Carabas had only to cast two or three respectful and somewhat tender glances at her but she fell head over heels in love with him. The king asked him to enter the coach and join them on their drive. — Charles Perrault, "The Master Cat or, Puss in Boots."

Commentary

For Dick Whittington the cat merely does what comes naturally to bring its owner wealth. Puss in Boots, on the other hand, wins for his master, the youngest and poorest of three brothers, the crops and wealth worked for by others through his own deceit and is far more humanized. (Daniels 2002)

The King's carriage here very much resembles the British monarch's Gold State Coach, an enclosed, eight horse-drawn carriage commissioned in 1760, and built in the London workshops of Samuel Butler. Since this ornate vehicle, now on display at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace, has been used for the coronation of every British monarch since King George IV, Cruikshank would undoubtedly have seen it — as would most Londoners lining the streets to Westminster Abbey — at the coronation of young Queen Victoria on 28 June 1838, a pageant watched by denizens of the metropolis and some 400,000 people from the country who had travelled into London by the new railways. The coach's age, enormous weight, and general lack of manoeuvrability have limited its use to grand state occasions such as coronations, royal weddings, and royal jubilees; it is hardly the sort of vehicle that the royal family would have routinely used for trips through the countryside, but Cruikshank has admirably adapted it as the king's carriage in Puss in Boots. Since the State Coach weighs four tons and is 24 feet (7.3 m) long and 12 feet (3.7 m) high, Cruikshank has shrunk it considerably for the purposes of illustration.

The point of attack that Cruikshank uses enables him to move the story along more quickly than Perrault did, even though he offers considerably more detail about Puss and his plan to render Caraba an eligible aristocratic bachelor by introducing him to the Princess dressed in the latest Renaissance court fashion rather than peasant's rags. Despite Cruikshank's later attempting to point the moral that, as Dickens remarks at the close of Great Expectations (1861), one should assess whether a man is a "gentleman" not based on his appearance and clothing, but on his actions:

although the mill, being on high ground, was in a high position, it may be thought that the trade of a miller was not so; but let me observe that if any one in trade is not considered in a high position in society, he must, nevertheless, be highly respectable, if useful and honest. — Cruikshank, "Puss in Boots," p. 24.

Cruikshank here attempts to extend the concept of social "respectability" to those who have become rich through business rather than inheriting titles and estates, but he cannot dismiss the effect that Caraba in his elegant clothing has upon the princess; apparently, appearance can be both deceptive and engaging.

Cruikshank's two scenes involving Caraba at the riverbank, particularly this of his approaching the royal carriage in his new clothes, emphasize the happy coincidence of the meeting between Puss's master and the royal travellers. The illustrator again includes sufficient details to render the images (and the speeded up timeline of the story) credible. Although in Perrault, Puss took months to put into motion his marriage scheme, in Cruikshank's version this scene occurs the day after Puss's presenting the brace of rabbits to the King in Tom Puss presenting a Rabbit to the King..on the Royal Podium (facing page 8). Placing the cat-servant against the wheel of the ornate royal vehicle, Cruikshank reminds us of Puss's size. Cruikshank includes a brace of armed footmen on either side of the carriage and the horse-guards at the rear to suggest an extensive entourage that the following frame, Tom Puss commands the Reapers to tell the King that All the fields belong to the Most Noble, the Marquess of Carabas, will show in perspective as Tom advances his scheme to overthrow the ogre and effect the marriage of his master and the princess. For the sake of continuity, Cruikshank has shifted the location of the tree from the right in the previous panel to the left to accompany the shift in perspective as Caraba has moved from an inferior to a central position, and the carriage itself seems to have shifted forward a few feet. The heads of the driver, the king and his daughter, and the second footman all create a downward, right-to-left diagonal that culminates in the slightly bowing figure of the youth.

The initial scene involving the King and the Princess in their ornate carriage

Above: George Cruikshank's initial realisation of the King's state carriage approaching the estates of the Marquis of Carabas, Tom Puss telling the King that his Master .. the Marquiss of Carabas, is in the River (also facing page 12). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Carpenter, Humphrey, and Mari Pritchard. The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1984.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Puss in Boots. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The fourth volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: Routledge, Warne & Routledge, 1864. (Price one shilling) 11 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Daniels, Morna. "The Tale of Charles Perrault and Puss in Boots." Electronic British Library Journal. 2002. pp. 1-14. http://docplayer.net/21672800-The-tale-of-charles-perrault-and-puss-in-boots.html

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kotzin, Michael C. Dickens and the Fairy Tale. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1972.

Perrault, Charles. "The Master Cat or, Puss in Boots." Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts, University of Pittsburgh, 2002. From Andrew Lang's The Blue Fairy Book (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., ca. 1889), pp. 141-147. Edited by D. L. Ashliman. http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/perrault04.html

Schlicke, Paul. "

Stone, Harry. Dickens and the Invisible World: Fairy Tales, Fantasy, and Novel-Making. Bloomington, IN: Indiana U. P., 1979.

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 7 July 2017