The Heralds proclaiming the Prince's wish, that all the Single Ladies should try on the Glass Slipper! (7 cm high by 9.7 cm wide, vignetted, facing page 20) — the eighth illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1854 and for the third tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. The context is the arrival of the King's heralds with the glass slipper for fitting contest, the proclamation for which the Herald (centre) holds out, as if showing to the step-sisters (down right). However, whereas previous illustrations have suggested that Cinderella's family live out in the country, the backdrop here, with the balcony overlooking the square (upper left) is markedly urban — in fact, the churches depicted in the background (a domed, Renaissance cathedral and a square-towered Romanesque church) suggest an Italian city such as Florence. A typical Cruikshank touch is the Cockapoo-like dog barking at the strangers as Cinderella peeks out at the proceedings from the kitchen, extreme right, while her sisters in the foreground speculate as to why they are receiving this visit from the King's minions carrying a glass slipper on a cushion. Guards in plate armour and carrying halberds further connect this scene with the scene in which Cinderella escapes from the palace at the stroke of twelve, Cinderella, leaving the Royal Palace after the Clock had Struck Twelve! (facing page 19). The trumpeters sound their instruments to announce the Herald's reading the Royal proclamation, as children in Italian Renaissance garb look on from the left, giving the picture a theatrical quality.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Passage Illustrated

On the following morning at an early hour, the town was aroused by the blowing of trumpets, and, upon the people coming out to know the occasion of it, they found two of the Royal herald trumpeters, with a Chamberlain, guards, and an attendant carrying a crimson velvet cushion, upon which was placed a glass slipper. When the trumpeters had blown a flourish, the Chamberlain read a proclamation, to the effect that the Royal Prince requested all the single ladies should try on this glass slipper, and declared that whomsoever it micjht fit he would make his bride. Oh! then immediately followed such a trying on — such efforts to squeeze in their dear little feet; but no! not one could get the glass slipper on, not even half-way; some could not get their toes in, — for the more they tried, the more it seemed to shrink, — and the Chamberlain requested that they would not use it too roughly, lest they should break the spun-glass covering.

The Chamberlain and attendants had gone nearly all over the town, and were growing weary, when they turned to where Cinderella lived, which was a little out of the road. The sisters were standing at the kitchen door, the mother at her bedroom window, for she was still unable to leave her room, and poor Cinderella in her dingy dress was peeping over her sisters' shoulders. — "Cinderella and The Glass Slipper," pp. 18-16.

The Context in Perrault

They told her, yes, but that she hurried away immediately when it struck twelve, and with so much haste that she dropped one of her little glass slippers, the prettiest in the world, which the king's son had picked up; that he had done nothing but look at her all the time at the ball, and that most certainly he was very much in love with the beautiful person who owned the glass slipper.

What they said was very true; for a few days later, the king's son had it proclaimed, by sound of trumpet, that he would marry her whose foot this slipper would just fit. They began to try it on the princesses, then the duchesses and all the court, but in vain; it was brought to the two sisters, who did all they possibly could to force their foot into the slipper, but they did not succeed. — Chales Perrault, "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper."

The other scenes containing the Prince

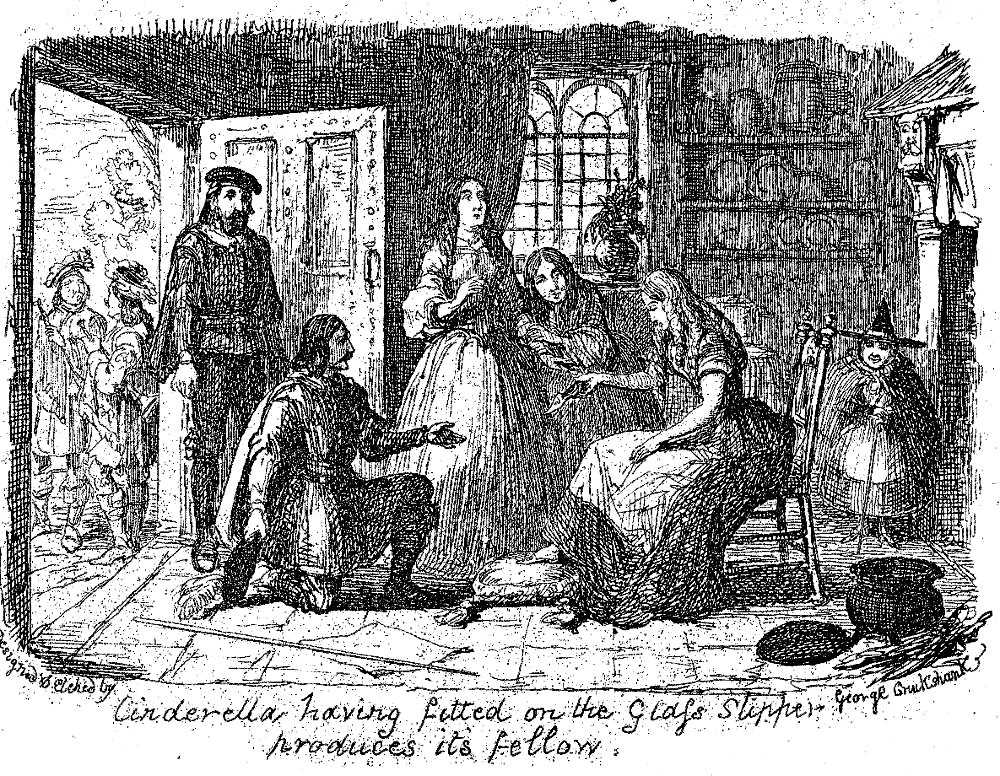

Left: George Cruikshank's initial realisation of the handsome Prince, left, as he discovers and is about to pick up the glass slipper which Cinderella has just lost, The Prince, picking up Cinderella's Glass Slipper (1854). Centre: The finalé of the romance of the Prince and the pauper, The Marriage of Cinderella to The Prince (facing page 26). Right: Cruikshank's exciting scene in which the Prince fits the magic slipper on the heroine, with the Fairy Godmother watching the proceedings from the side, Cinderella having fitted on the Glass Slipper produces its Fellow (facing p. 20). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Commentary

After the former illustration, The Prince, picking up Cinderella's Glass Slipper, the logical consequence or next step in the narrative chain of events is the Prince's attempting to find the owner of the glass slipper. Cinderella has lost one of her glass slippers as she panics about the lateness of the hour on the night of the second ball, in Cinderella, leaving the Royal Palace after the Clock had Struck Twelve!. Unlike the Seven-league Boots in "Hop-o' My-Thumb," the magic slipper is not elastic: it fits only Cinderella, and therefore sets her apart from all the other marriageable maidens in the kingdom. Since that loss, the pair are incomplete — like the Prince and Cinderella, so that the successful matching of slipper and owner in the next frame, Cinderella having fitted on the Glass Slipper produces its Fellow (bottom of tipped-in illustration, facing page 20) is the climax of the story, — and the moment that serves as a metonymy for the entire rags-to-riches tale. In The Dickens Index, Bentley et al. note that Dickens's focus in his allusions to the story is the glass slipper:

Cinderella's slipper, the slipper (fur in Perrault's version of the story, glass in the English version) left behind when Cinderella flees from the ball before midnight should strike, and she be changed back into her rags. The love-struck Prince searches through all the realm to find the foot that will fit the slipper, eventually discovering the rightful owner despite obstruction from her Ugly Sisters. — Bentley et al., p. 55.

Dickens specifically alludes to the glass slipper in Dombey and Son, Chapter 6, "Paul's Second Deprivation," when the witch-like Mrs. Brown, an "anti-Fairy Godmother" like Fagin in Oliver Twist, has stripped Florence of her costly clothing and dressed her in rags, and then cast her adrift in "The Great Oven." Miraculously, Florence finds her way to the Dombey wharf, where the kindly manager entrusts her to Walter Gay of her father's business:

Mr. Clark stood rapt in amazement: observing under his breath, I never saw such a start on this wharf before. Walter picked up the shoe, and put it on the little foot as the Prince in the story might have fitted Cinderella’s slipper on. He hung the rabbit-skin over his left arm; gave the right to Florence; and felt, not to say like Richard Whittington — that is a tame comparison — but like Saint George of England, with the dragon lying dead before him.

"Don't cry, Miss Dombey," said Walter, in a transport of enthusiasm. "What a wonderful thing for me that I am here! You are as safe now as if you were guarded by a whole boat's crew of picked men from a man-of-war. Oh, don't cry." — Dombey and Son, pp. 39-40.

Walter Gay, in other words, restores her name and identity to the victimized Florence, as if he were the Prince discovering his bride in the scullery girl. Dickens also alludes to the glass slipper from "Cinderella" in Little Dorrit, Book One, Chapter 2 ("Fellow Travellers"), when the practical but warm-hearted man of business Mr. Meagles recounts how he came to adopt the fancifully-nicknamed Tattycoram:

"So I said next day: Now, Mother, I have a proposition to make that I think you'll approve of. Let us take one of those same little children to be a little maid to Pet. We are practical people. So if we should find her temper a little defective, or any of her ways a little wide of ours, we shall know what we have to take into account. We shall know what an immense deduction must be made from all the influences and experiences that have formed us — no parents, no child-brother or sister, no individuality of home, no Glass Slipper, or Fairy Godmother. And that's the way we came by Tattycoram." — p. 10.

In the Cruikshank illustration, the presences of the Prince and the Fairy-Godmother are only implied, but Cruikshank emphasizes the importance of the slipper by positioning the Romanesque bell-tower immediately above the functionary carrying the slipper on the scarlet cushion, centre. The aerial perspective afforded by the cityscape backdrop suggests the distance that the royal party has come from the palace in order to effect the trial, which occurs in the very next panel.

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Chesson, W. H. "From George Cruikshank's Fairy Library, 'Cinderella,' 1854." George Cruikshank. London: Duckworth, 1920.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Cinderella and The Glass Slipper. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The third volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: David Bogue, 1854. (Price one shilling) 10 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Dickens, Charles. "Frauds on the Fairies." Household Words. A Weekly Journal. Conducted by Charles Dickens.. 1 October 1853. No. 184, Vol. VIII. Pp. 97-100.

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kotzin, Michael C. Dickens and the Fairy Tale. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1972.

Perrault, Charles. "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper." Fairy Tales and Other Traditional Stories. Lit2Go. http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/68/fairy-tales-and-other-traditional-stories/5089/jack-and-the-bean-stalk/

Schlicke, Paul. "

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 3 July 2017