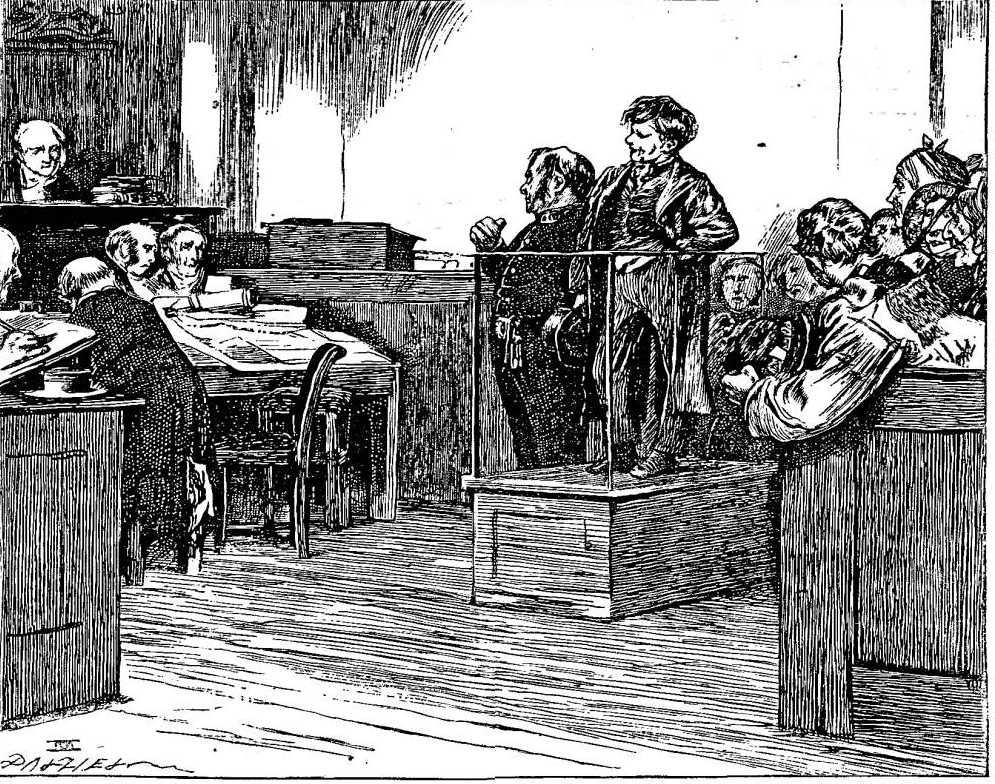

From the Bar of the Gin Shop to the Bar of the Old Bailey It Is But One Step. — George Cruikshank. 1848. Fifth illustration in The Drunkard's Children. Folio page: 46 x 36 cm (24 inches by 14.5 inches), framed. The etchings were reproduced by glyphography, "enabling the publisher [David Bogue, London] to sell the entire series for one shilling" (Vogler, p. 159). "This suite appeared in similar size and editions to that of The Bottle, but it was never reissued in smaller format" (Vogler, p. 161), except that throughout this sequel the majority of the scenes are not individually signed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary

Is childhood poverty rather than parental alcoholism the logical determinant of a child's growing up to become a criminal? Charles Dickens and George Cruikshank have provided radically different answers. Whereas Dickens answered in a number of his novels and short stories, beginning with The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, Cruikshank provides a response that targets drink as the culprit in The Drunkard's Children. The Drunkard's son, having fallen into bad company after his mother's murder and his father's incarceration, now faces the dread sentence for having participated in a capital crime. As Richard A. Vogler points out, he is far more expressionless than his sister during their arraignment in the Criminal Court of the Old Bailey: “The girl weeps and the boy sadly looks straight ahead toward the judge whose presence is felt but whose person is not visible in this almost photographically accurate depiction of a nineteenth-century English courtroom. The jury is seen on the right; the lawyers, in the foreground. A few spectators look down from the upper gallery. Judging from the look on the boy's face, one concludes it almost inevitable that he will be found guilty. [Vogler, pp. 161-62). The fifth illustration removes us and the Drunkard's children from sordid scenes of vice and debauchery, and, after the son's arrest in a low lodging-house, takes us directly to his trial in the Middlesex Criminal Court. Cruikshank's plate again features a crowd, but of lawyers rather than drinkers, gamblers, or dancers. Cold, dispassionate, and professional, the attorneys and functionaries of the legal system seem oblivious to the feelings of the accused. Although this scene would offer, in an earlier Cruikshank illustration, "a traditional gorgeous subject for caricatures, . . . here there is no memorable variety of type and passion in the massed legal faces" (Harvey, p. 150). Indeed, the faces of most of the characters bear some resemblance to one another, and a fasshionably dressed young man watching the proceedings from immediately below the prisoner's docket bears a striking resemblance to the brother. Record-keeping rather than speaking and listening dominates the courtroom as the Drunkard's son becomes an anonymous case number.

Compare this Cruikshank courtroom scene with those of Phiz, for example, in the Pickwick Papers, The Trial, and in A Tale of Two Cities, The Likeness. Whereas Phiz in the former describes the barristers at the Old Bailey as querulous, quaintly costumed, and amusing caricatures, and individualises them through their poses and expressions, Cruikshank generalizes his business-like attorneys, and focusses on the physically and emotionally alienated figures of the melancholy defendant and his distraught sister. The artist finds nothing laughable or even worthy of caricature in the 1848 scene at the Old Bailey, which, aside from the prostrate sister, is singularly prosaic.

In a very different vein, Dickens presents the magistrate's court scene in which the Artful Dodger receives a similar sentence for a much less significant crime: pickpocketing. Through the voice of the Cockney wit, the author of Oliver Twist transforms the judicial proceedings into a satire on the law, as the Dodger banters with the magistrate. However, in accordance with actual legal procedure, the magistrates must be seated on the other side of the room, outside our field of vision (indeed, immediately behind us). Although equally sympathetic to the accused, Cruikshank nevertheless remains in dead earnest here. The sister's emotional breakdown contrasts the dead-pan expressions of the lounging spectators, seated behind and above the jurors in a constricted gallery. What strikes one most about Cruikshank's courtroom scene is the utter indifference of everybody to the fate of the Drunkard's son. The absence of the magistrates from the frame renders the sentencing more impersonal; a system rather than a person finds him guilty and sends him abroad. On the other hand, Phiz has made his depiction of the Old Bailey trial of Charles Darnay for espionage far more animated; those who pack his courtroom take great interest in the legal proceedings and in the handsome, noble defendant (whom both Sydney Carton and Jerry Cruncher are studying). In contrast, Cruikshank's depiction of the trial (possibly in the very same 1774 courtroom) is devoid of such emotional engagement and animation. Moreover, those charged and in the prisoner's box appear to have no advocate. Curiously, Cruikshank has omitted the sounding board placed over the prisoners' heads in order to amplify their voices.

One should also consider the differences between Cruikshank's earlier courtroom scenes, in particular in the Newgate novel Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens, in which survives Cruikshank's original notion of an earlier visual project, Life of a London Thief, which apparently predated the Dickens novel by fifteen years. The illustrator may well have borrowed interrogation and courtroom scenes from his folio, dating from the 1820s, for the Dickens novel and the rogue novel Jack Sheppard by William Harrison Ainsworth. Generally, Cruikshank in these earlier scenes derides the pretentions of those in authority, and sides with the accused. Whereas he maintains his caricature of the pompous Bumble in Oliver Escapes Being Bound to a Sweep (1837), in which a mere child must confront a quasi-judicial body, the Governors of the Workhouse, the artist finds nothing laughable in the 1848 scene at the Old Bailey. After the court has sentenced the Drunkard's hapless son, a victim of circumstances, to criminal transportation, the boy dies on the temporary prison facility called a "hulk," and never actually makes the voyage to Australia.

The illustrator enhances the scene's verisimilitude through details such as the spikes on the bar to one side of the prisoners and the aromatic herbs on the bar in front of them. These appeared in the courtroom after 1750 as a way of combatting the danger of infection and gaol fever or typhus; nosegays and aromatic herbs also kept down the stench. Through the three structures immediately outside the window Cruikshank creates a sense of the City beyond the trial. Aside from a house to the left, which perhaps represents respectable, middle-class society, the salient features are the triumphal arch and the church tower. The latter matches that of St. Sepulchre-without-Newgate, also known as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Holborn), located opposite the Central Criminal Court, and just beyond the now demolished mediaeval walls of The City of London. The name of the church in the nursery rhyme "Oranges and Lemons" (involving six City churches) comes from its proximity to the criminal court: "'When will you pay me?' Say the bells of Old Bailey." The third structure, dominating the scene outside the rear window, serves a symbolic rather than a literal function since Marble Arch, suggestive of royal prerogative, has never been situated near the Old Bailey. Designed by architect John Nash in 1827 as the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace, Marble Arch was dismantled in 1847 and rebuilt in 1850 by Thomas Cubitt as a ceremonial entrance to the northeast corner of Hyde Park at Cumberland Gate.

One must bear in mind certain dates in assessing the verisimilitude of the young protagonist's receiving a sentence of "transportation for life" since during the 1840s the British government was winding down the whole system of penal servitude. "True, the Swan River colony in Western Australia continued to receive convicts until 1868, but in the East transportation to Van Diemen's Land ended in 1825 and to New South Wales in 1838" (Dilnot, p. 29). In all likelihood, Cruikshank based his conception of the transportation of convicts to the Australian colonies, as did Dickens in Artuful Dodger's being sentenced to transportation in Oliver Twist, upon conditions which had existed earlier in the nineteenth century. A spirit of the need for reform permeates Cruikshank's plates concerning the fate of the Drunkard's son, but such reforms were already well under way by 1848.

The Household Edition Scene of the Dodger's Sentencing

Above: James Mahoney's realistic wood-engraving of the self-confident Dodger, bantering with the magistrate during his trial for petty larceny, in "What is this?" inquired one of the magistrates. — "A pick-pocketing case, Your Worship." [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Related Material

- The Parliamentary Report on Transportation (1838)

- Crime in Victorian England

- Oliver Escapes Being Bound to a Sweep (1837)

- A Pickpocket in Custody (1839)

- "What is this?" inquired one of the magistrates. — "A pick-pocketing case, Your Worship."

- The Old Bailey

- The Punishment of Convicts in Nineteenth-Century England

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

Bibliography

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. The Drunkard's Children. A Sequel to "The Bottle." London: David Bogue, 1848.

Dilnot, Alan. "The Doger Transported." The Dickens Magazine 8, 2 (August 2017): 29-30.

Harvey, John. "George Cruikshank: A Master of the Poetic Use of Line." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 129-156.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kunzle, David. "Mr. Lambkin: Cruikshank's Strike for Independence." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 169-88.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Meisel, Martin. Chapter 7, "From Hogarth to Cruikshank." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1989. Pp. 97-141.

Mellby, Julie L. "More than 100,000 copies sold in the first few days." Graphic Arts: Exhibitions, acquisitions, and other highlights from the Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton University Library. Web. 13 April 2011. https://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2011/04/the_bottle.html

Pritchett, V. S. "A Fine Rough English Diamond: A Review of Graphic Works of George Cruikshank, selected and with an introduction and notes by Richard A. Vogler. Dover Publications, 168 pp., 279 illustrations, $7.95 (paper)." The New York Review of Books 12 June 1980. Pp. 5-8.

Sutherland, John. "Lloyd, Edward." The Stanford Guide to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford U. P., 1989. P. 380.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Williams, Tony. "Over the Seas and Far Away, or the English Gulag — Transportation and the Hulks." The Dickens Magazine. (2000) Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 8-9.

Last modified 7 September 2017