Cold, Misery, and Want, Destroy Their Youngest Child: They Console Themselves with the Bottle — George Cruikshank. 1847. Fifth illustration in The Bottle. Folio page: 46 x 36 cm (24 inches by 14.5 inches), framed. The etchings were reproduced by glyphography, "enabling the publisher [David Bogue, London] to sell the entire series for one shilling" (Vogler, p. 159). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Analysis

This plate depicts the penury that intensifies the family's suffering, immediately confirming the previous one’s subtle foreshadowing of the tombstones and leafless tree: a child's coffin, which the surviving daughter tearfully regards, occupies the central upstage position. Blanchard Jerrold explains that

In the fifth plate, "cold, want, and misery" have destroyed their youngest child, and still "they console themselves with the bottle." A little open coffin is in the room, and while the eldest girl weeps over it, the father and mother drink, and weep also. A broken toy dog is upon the mantelpiece near a candle, with a bottle for a candlestick. An old shawl is fastened before the window with a fork. There are only a few sticks in the fire. [p. 251]

Richard A. Vogler echoes Jerrold in his 1979 assessment that contrasts the black gin bottle and the broken toy:

The family is again seen in a room identical in size and shape to that of their original abode, but all of the possessions are gone except for one broken toy. This apparently belonged to the smallest child, now dead and resting in the wooden casket near the rear wall. The daughter weeps. The son, hand on head, looks understandably anguished. The wife, with a glass of gin in one hand, holds a rag to her tearful face. The husband holds the infamous black bottle in his right hand, his look of despair foreshadowing his inevitable doom — insanity. ["Notes on the Illustrations," p. 160.]

The Hogarthian embedded text in this plate appears on a crumpled piece of paper lying at the feet of the grieving son: "Designed and Etched by George Cruikshank" (right). The crack which had appeared on the wall in the distraining scene has widened considerably, presenting a sort of negative halo of bare lath and crumbling plaster above the father's head. The barren room, completely denuded of the decorations which made it the centre of the Victorian home in Plate 1, has become a stark study in black-and-white contrasts created by the white of the bare plaster walls, cupboard, and door against shadows of mother and daughter, smoke from the fitful fire in the grate, the back shawl of the mother, and the tattered black suit of the father. Whereas the other family members have withdrawn into themselves, the father stares unblinkingly at the viewer, as if asking not for sympathy but for a rational appraisal of the circumstances in which he and his family now find themselves. Only a child's chair and the wife's chair remain; the father is reduced to sitting on a packing box. Although the dish, which appears at the lower left, is chipped and empty, the father still has the additional consolation of a pipe and a little tobacco (on the mantelpiece), even if, lacking a glass himself, he must drink his gin straight from the bottle. At first glance, what is rolled up in the left-hand corner appears to be a carpet; it is, in fact, a single mattress, presumably where all family members sleep together.

Above: George Cruikshank's materialistically "happy home" in the first of the illustrations in the 1847 sequence, The Bottle Is Brought Out for the First Time: The Husband Induces His Wife "Just to Take a Drop." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Relevant death-bed scenes in other illustrations of the period, 1841-69

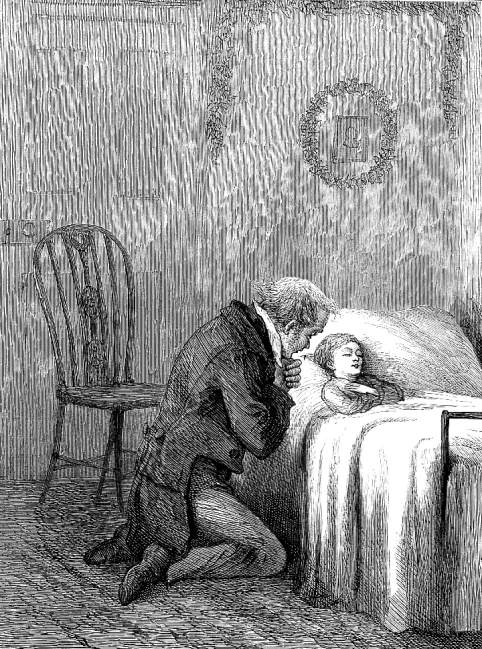

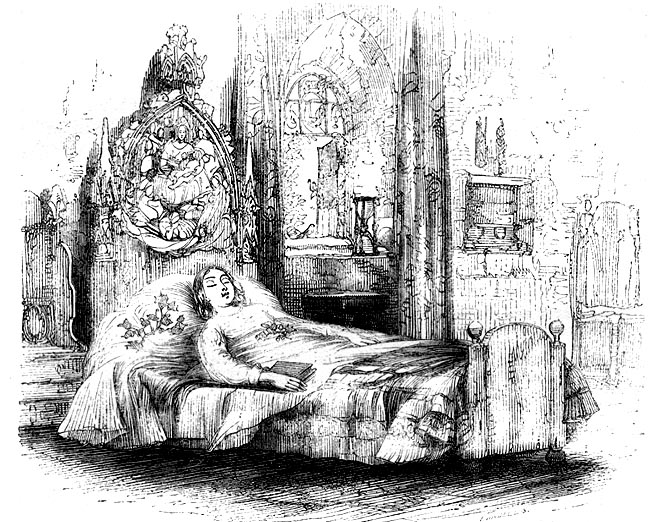

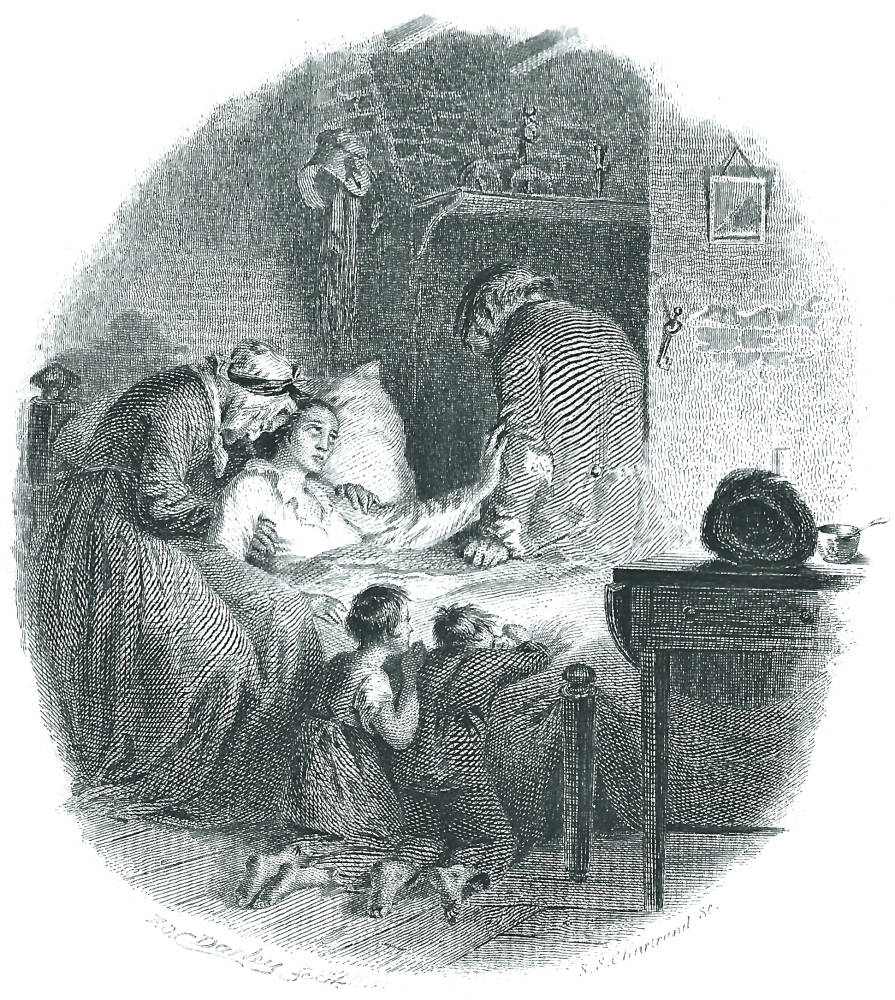

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's sentimental image of Bob Cratchit's praying at the deathbed of his crippled son in A Christmas Carol, Poor Tiny Tim! (1869). Centre: The celebrated image of the death an angelic child by George Cattermole for The Old Curiosity Shop, ["At Rest (Nell dead)"] (30 January 1841). Right: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's realisation of the death an an alcoholic father, surrounded by grieving family members, The Drunkard's Death (1864). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The illustrator in this instance has chosen not to exploit the child's death, even muting the reactions of the parents and siblings, and not actually displaying her body. His approach, as opposed to those of Eytinge, Darley, and Cattermole, is markedly anti-sentimental — he does not even show the child dying or the family grieving at her bedside, leaving such scenes to the viewer's imagination. Since Cruikshank is sparing in his captions and is chiefly interested in the fortunes of the parents, he offers no explanation for the child's death, leaving the viewer to supply the cause.

Related Material

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- The Gin-Shop

- "Great is thy power, O Gin" — Reynold's sermon on the harm it does to the poor

- London Gin Shops

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Temperance, Teetotalism, and Addiction in the Nineteenth Century

- Addiction in the Nineteenth Century

- Drunkedness and the ease of obtaining alcohol

- Alcohol and Alcoholism in Victorian England

- The Band of Hope Review

- Charles Dickens and Two Kinds of Punch, 1. The Beverage

Bibliography

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

James, Louis. "An Artist in Time: George Cruikshank in Three Eras." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 156-187.

Jerrold, Blanchard. "Epoch Two, 1848-1878. Chapter 2, The Bottle." The Life of George Cruikshank. In Two Epochs. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus, 1882. Vol. 2, Pp. 248-255.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Meisel, Martin. Chapter 7, "From Hogarth to Cruikshank." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1989. Pp. 97-141.

Mellby, Julie L. "More than 100,000 copies sold in the first few days." Graphic Arts: Exhibitions, acquisitions, and other highlights from the Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton University Library. Web. 13 April 2011. https://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2011/04/the_bottle.html

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 9 August 2017