Hunted Down by George Cattermole. 3 ½ x 4 ½ inches (9 cm by 11.7 cm). Vignetted, wood-engraved. Master Humphrey's Clock, No. 3 (18 April 1840), ninth plate in the series. Part 3, "A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second," p. 36. [Click on the images to enlarge them. Mouse over links]

Passage Illustrated: The Child-killer Apprehended in His Own Garden

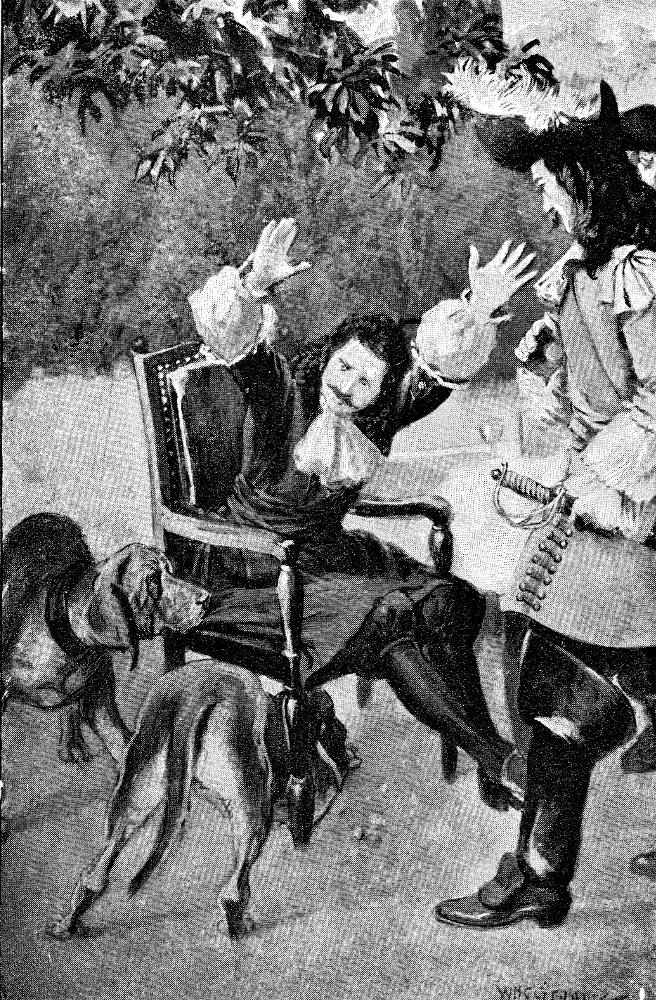

W. H. Groome's full-page illustration for this story in the Collins Pocket Edition: "I’ll never leave this place!". (1907), showing the madman in his garden, sitting on top of the concealed grave.

"In Heaven’s name, move!" said the one I knew, very earnestly, "or you will be torn to pieces."

"Let them tear me from limb to limb, I’ll never leave this place!" cried I. "Are dogs to hurry men to shameful deaths? Hew them down, cut them in pieces."

"There is some foul mystery here!" said the officer whom I did not know, drawing his sword. "In King Charles’s name, assist me to secure this man."

They both set upon me and forced me away, though I fought and bit and caught at them like a madman. After a struggle, they got me quietly between them; and then, my God! I saw the angry dogs tearing at the earth and throwing it up into the air like water. ["A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second," 36]

Commentary: The Demented Murderer and the Arresting Officers in the Garden

The editor of Master Humphrey's Clock, twenty-eight-year-old Charles Dickens, has positioned Cattermole's elegant illustration of the culminating garden scene street in the middle of the passage it complements. Cattermole directs the demented killer's gaze not at his arresting officers (right) but at the viewers, as if to enlist them in his cause. Again, as in Death of Master Graham, Dickens has described the death of an innocent, but here his emphasis is clearly on the killer rather than the victim. The artist realizes the garden in the killer's estate a few miles east of London in 1679. However, the first-person, retrospective narrative "A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second" smacks of the narrative strategy of Edgar Allen Poe in having the consciousness of a demented, disturbed, or even psychotic personality filter for the reader the events of the story — a story that culminate in the murderer's unmasking and detention for his heinous crime, in which the narrator makes the reader almost a co-conspirator. Cattermole has the madman solicit the reader's understanding even as the officers of King Charles arrest him on the very spot where he has buried the child's body.

The story is remarkable for its self-justifying but unnamed narrator, a retired soldier who conceives an inveterate dislike of his young nephew, heir to his brother's estate. Brilliantly impersonated by the twenty-eight-year-old author, the fluent but obsessed narrator seems reminiscent of similarly unreliable first-person narrators of Edgar Allen Poe: "The Cask of Amontillado" (November 1846), "Tell-Tale Heart" (1843), and "The Black Cat" (19 August 1843). However, the only such Poe narrator that Dickens could have encountered prior to the spring of 1840 would have been the narrative voice of "Ligeia" (18 September 1838). In volume form, Poe's Tales of Mystery and Imagination did not appear in print until 1849, the year of his death.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions (1872-1910)

Left: Harry Furniss's focus is on the killer, hiding in the shrubbery, rather than on his innocent victim: The Murderer Has His Victim in his Net (1910). Right: Fred Barnard in the Household Edition depicts the madman, spying on his victim: "As he sat upon a low seat beside my wife, I would peer at him for hours together from behind a tree" (1872).

Other Illustrated Editions of Master Humphrey's Clock

- Harry Furniss's Six Charles Dickens Library Edition Illustrations for Master Humphrey's Clock (1910)

- W. H. C. Groome's Illustrations for Master Humphrey's Clock (1907)

- Fred Barnard's Four Household Edition Illustrations for Master Humphrey's Clock (Vol. XX, 1879)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cattermole." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 125-134.

Davis, Paul. "Master Humphrey's Clock." Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to his Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998. P. 238.

Dickens, Charles. Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by George Cattermole and Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 4 April 1840 — 4 December 1841.

_______. Master Humphrey's Clock. The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Reprinted Pieces, and Other Stories. With thirty illustrations by L. Fildes, E. G. Dalziel, and F. Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. XX. Pp. 253-306.

_______. Master Humphrey's Clock and Pictures from Italy. With eight illustrations by W. H. C. Groome. Collins Pocket Editions. London and Glasgow: Collins Clear-type Press, 1907. Vol. XLIX. Pp. 1-168.

_______. Barnaby Rudge and Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Volume VI. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture Book: A Record of the Dickens Illustrators. Ch. XIV. "Master Humphrey's Clock." The Charles Dickens Library. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Pp. 259-265.

Patten, Robert L. "Cattermole, George." In Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 68-69.

Vann, J. Don. "The Old Curiosity Shop in Master Humphrey's Clock, 25 April 1840 — 6 February 1841." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 64-65.

Created 30 August 2022