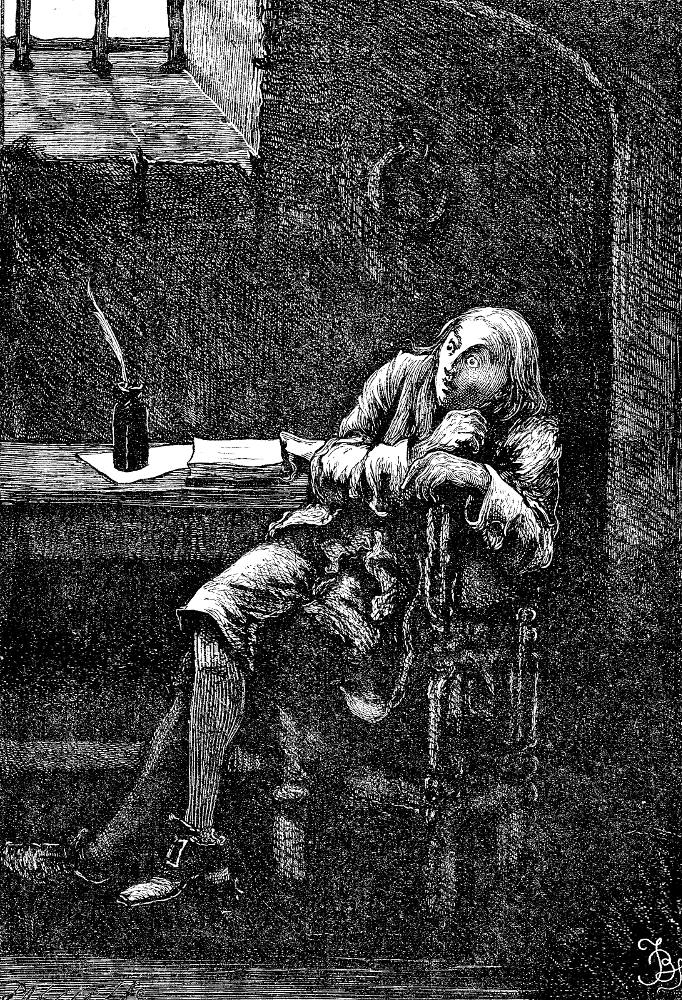

Lord George Gordon in The Tower by George Cattermole. 3 ⅝ x 4 ½ inches (9.3 cm by 11.5 cm). Framed, wood-engraved. Chapter LXXIII, Barnaby Rudge. 30 October 1841 in serial publication (sixty-eighth plate in the series). Part 38 in the novel, serialised in Master Humphrey's Clock, Vol. III (part 81), 367. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Lord George Gordon — A Prisoner for High Treason

And in the Tower, in a dreary room whose thick stone walls shut out the hum of life, and made a stillness which the records left by former prisoners with those silent witnesses seemed to deepen and intensify; remorseful for every act that had been done by every man among the cruel crowd; feeling for the time their guilt his own, and their lives put in peril by himself; and finding, amidst such reflections, little comfort in fanaticism, or in his fancied call; sat the unhappy author of all—Lord George Gordon.

He had been made prisoner that evening. "If you are sure it’s me you want," he said to the officers, who waited outside with the warrant for his arrest on a charge of High Treason, "I am ready to accompany you —" which he did without resistance. He was conducted first before the Privy Council, and afterwards to the Horse Guards, and then was taken by way of Westminster Bridge, and back over London Bridge (for the purpose of avoiding the main streets), to the Tower, under the strongest guard ever known to enter its gates with a single prisoner.

Of all his forty thousand men, not one remained to bear him company. Friends, dependents, followers,—none were there. His fawning secretary had played the traitor; and he whose weakness had been goaded and urged on by so many for their own purposes, was desolate and alone. [Chapter the Seventy-fourth, Vol. III, 367-68]

Commentary: What did the actual Lord George Gordon accomplish?

Harry Furniss's version of the same scene again paints a psychological

portrait of despondency:

Lord George Gordon (26 December 1751–1 November 1793), a Scots "eccentric," is remembered now (if at all) for having incited the "No Popery" riots in London on 2 June 1780. His intention was to lead a procession signalling widespread support for his initiative to repeal of the Catholic Relief Act of 1778. Despite his personal eccentricities, he was something of a social reformer. As an officer in the Royal Navy he tried to improve the living conditions of ordinary sailors. From the moment he entered Parliament in 1774 as the Member for the pocket-borough of Ludgershall (Wiltshire), he was a strident critic of the government's colonial policies in America. As a vocal supporter of American independence, Gordon frequently advocated for British subjects in the colonies. Some 50,000 members of his Protestant Association marched from St. George's Fields, just south of London, to the Houses of Parliament in Westminster in support of repealing the act which had restored political and civil rights to those Roman Catholics who were willing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Subsequently, however, the peaceful protest that the naive Gordon had planned turned violent; over the next few days, the urban mob burned Roman Catholic chapels at several embassies, pillaged the houses of well-known Roman Catholics, set fire to Newgate Prison to liberate 300 prisoners, broke open the city's other prisons, and attacked such public edifices as the Bank of England and 10 Downing Street, residence of Prime Minister Lord North.

Fred Barnard's version of the same scene does not show a

self-possessed prisoner, but one not clearly in possession of his faculties:

At this point, the government had to call in the army to quell the violence. Estimates of how many died range from 300 to 500, and the same number again were wounded. Although the authorities acquitted of treasonous intent thanks to the efforts of his gifted barrister, Thomas Erskine, Gordon was excommunicated by the Church of England for his refusa to testify in ecclesiastical court. He then publicly defamed the Queen of France, Marie Antoinette, and criticized the impartiality of British justice. He fled abroad, to Holland, but was forced by French authorities to return to England. In August 1786 in Birmingham at the age of 36, Gordon converted to Judaism, and was apparently utterly sincere in embracing the new faith. In January 1788 was sentenced to five years' imprisonment in Newgate, where he died of typhoid fever on 1 November 1793 at the age of 42.

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- George Cattermole, 1800-1868; A Brief Biography

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations (1841)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First Illustrators — A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's six illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 46 illustrations for the Household Edition (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's 6 illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

________. Barnaby Rudge — A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VII.

________. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. VI.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XIV. Barnaby Rudge." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 213-55.

Vann, J. Don. "Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February 1841-27 November 1841." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. 65-6.

Created 4 January 2006

Last modified 15 December 2020