The Shipwreck (p. 29) — the volume's tenth composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin), 1863-64. Chapter 3, "Wrecked on a Desert Island." The illustrator presents a convincing panorama of the wrecked merchantman off the coast of a remote island off the South American coast (left), with several small figures (presumably, one of them Crusoe). Full-page, framed: 14 cm high x 21.5 cm wide, including a frame of ropes and trees. Running head: "The Crew take to the Boat" (p. 30). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated

In this distress the mate of our vessel laid hold of the boat, and with the help of the rest of the men got her slung over the ship’s side; and getting all into her, let go, and committed ourselves, being eleven in number, to God’s mercy and the wild sea; for though the storm was abated considerably, yet the sea ran dreadfully high upon the shore, and might be well called den wild zee, as the Dutch call the sea in a storm.

And now our case was very dismal indeed; for we all saw plainly that the sea went so high that the boat could not live, and that we should be inevitably drowned. As to making sail, we had none, nor if we had could we have done anything with it; so we worked at the oar towards the land, though with heavy hearts, like men going to execution; for we all knew that when the boat came near the shore she would be dashed in a thousand pieces by the breach of the sea. However, we committed our souls to God in the most earnest manner; and the wind driving us towards the shore, we hastened our destruction with our own hands, pulling as well as we could towards land.

What the shore was, whether rock or sand, whether steep or shoal, we knew not. The only hope that could rationally give us the least shadow of expectation was, if we might find some bay or gulf, or the mouth of some river, where by great chance we might have run our boat in, or got under the lee of the land, and perhaps made smooth water. But there was nothing like this appeared; but as we made nearer and nearer the shore, the land looked more frightful than the sea. [Chapter III, "Wrecked on a Desert Island," page 30]

Commentary

The illustration on the shore of the Caribbean island that will be Crusoe's home for decades only subtly includes any indication that any of the crew have survived. The seascape implies that the novel will be concerned with voyages to foreign ports and adventures on the high seas. Indeed, if one regards shipping, shipwrecks, the sea, and sailors as a construct behind the illustrations, about thirty per cent of the Cassell's illustrations are associated with such a motif. A further twenty percent of the narrative-pictorial series involves foreigners and foreign locales.

Whereas earlier illustrators have focussed on Crusoe's struggling in the surf, the Cassell's artist has selected a subject that underscores the autobiographical and non-fiction facade of the story. The dark sky and tempestuous white-water engulfing the vessel recall the violent wrecks in the paintings of J. M. W. Turner, such as A Disaster at Sea (1835) and The Ship Wreck (1805). Although shipwrecks in the age before the accurate mapping of shoals and the widespread construction of lighthouses wereall too common, as the British in the nineteenth century engaged in such preventitive measures, the number of catastrophic incidents declined. However, as The Illustrated London News for the 1850s and 1860s shows, hurricane force winds could still force even fairly large merchant vessels on the rocks, as in The Wreck of the "Royal Charter" on the Coast of Anglesea, near Moelfre Five Miles from Point Lynas Lighthouse (5 November 1859). The Cassell's house-artist appears to have based his composition not upon an artistic model such as Turner's epic 1840 canvas Slavers Overthrowing the Dead and Dying —Typhoon Coming On (pertinent though this realisation of a 1781 incident would have been), but on an actual shipwreck depicted in the pages of The Illustrated London News, Wreck of an Indiaman." — From a Picture by Mr. Daniell (16 February 1859).The hand of Providence may well lie behind the wreck of Crusoe's slave-ship, and certainly the abolition of slavery must have been a current topic at the time that Cassell's published this lavishly illustrated Robinson Crusoe, in the midst of the American Civil War.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Related Scenes from Stothart (1790), the 1818 Children's Book, Wehnert (1862), and Cruikshank's (1831)

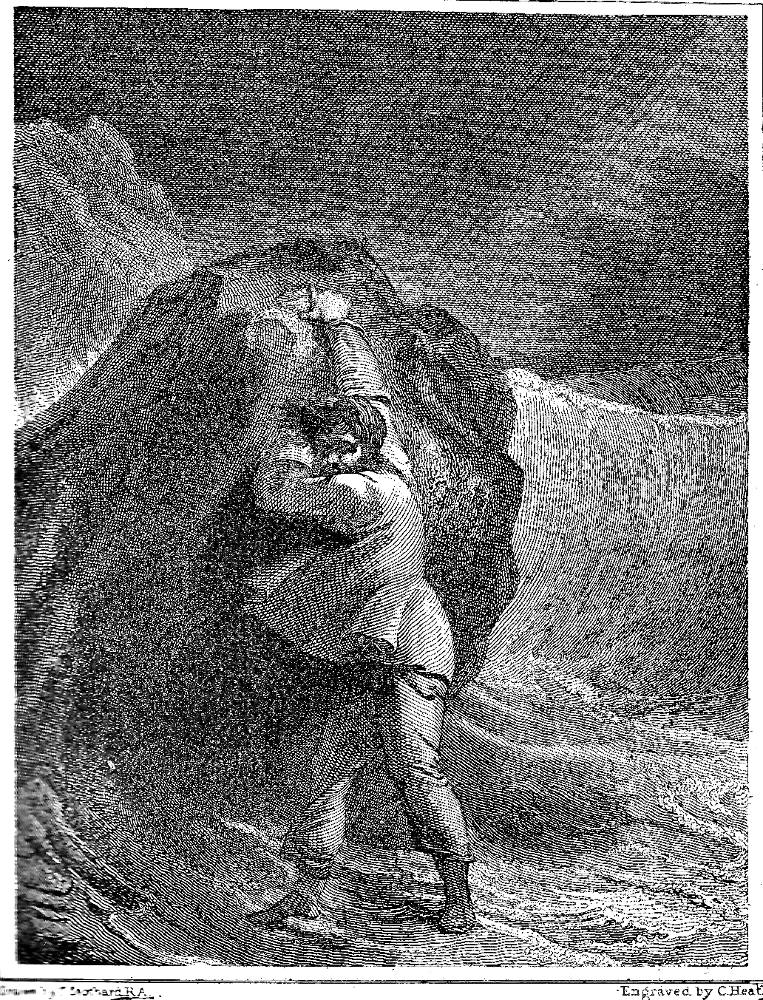

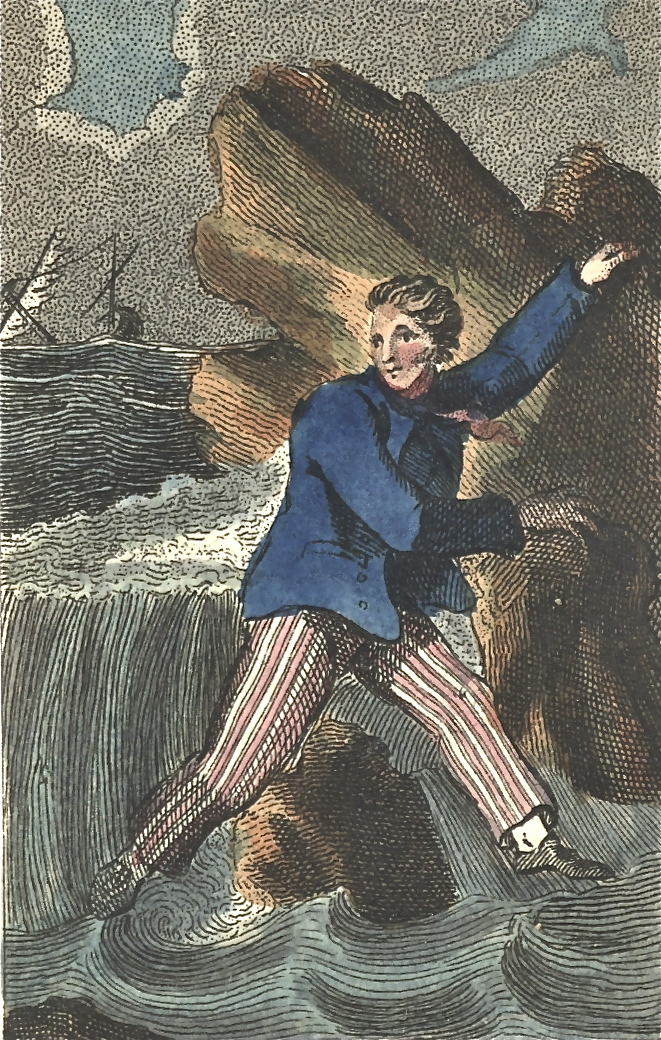

Right: Stothard's elegant realisation of Crusoe clinging to the rock, Centre: Wehnert's more dynamic realisation of the same episode, Crusoe saved on the island (1862: wood-engraving, Chapter III, "Wrecked on a Desert Island"). Right: Colourful children's book realisation of the same scene, but utterly lacking in realistic perspective: Robinson Crusoe cast away on the rock (1818). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

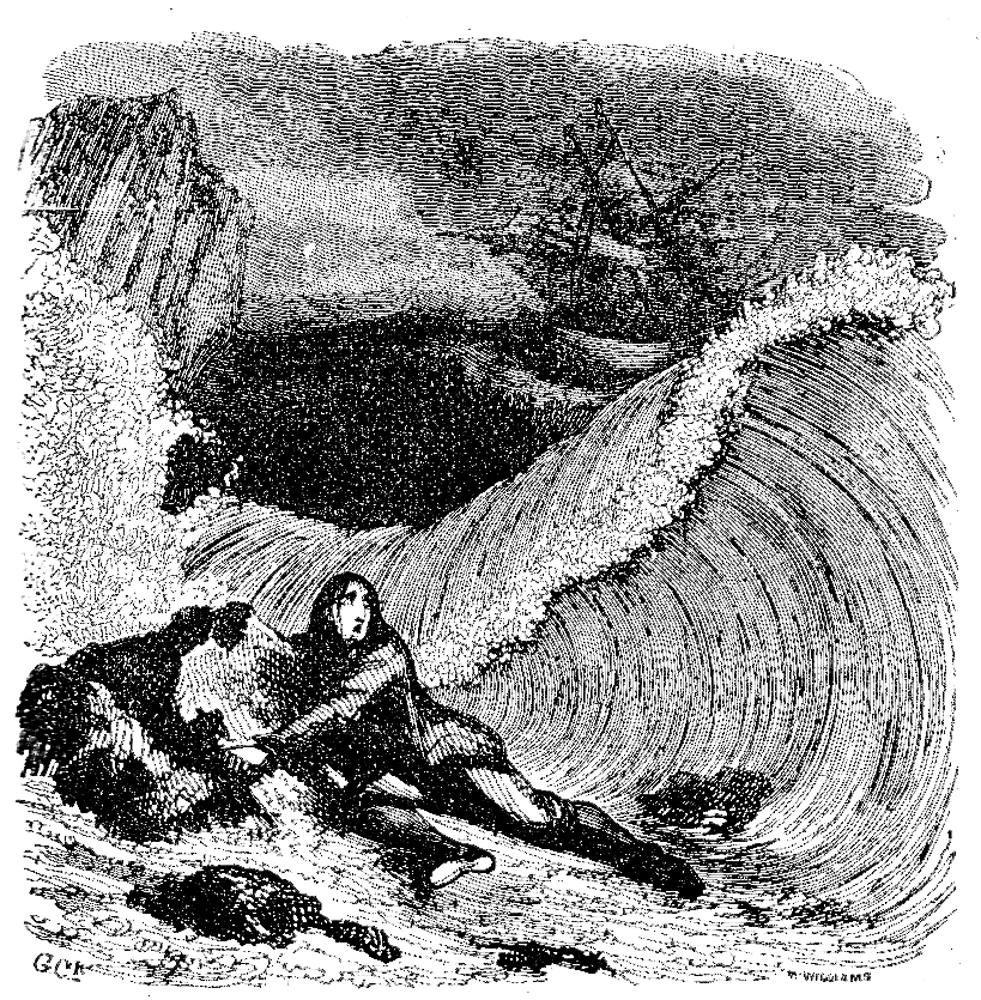

Above: George Cruikshank's sympathetic portrayal of Crusoe fighting for his life in the surf, Crusoe clinging to a rock on the beach. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

De Foe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 9 March 2018