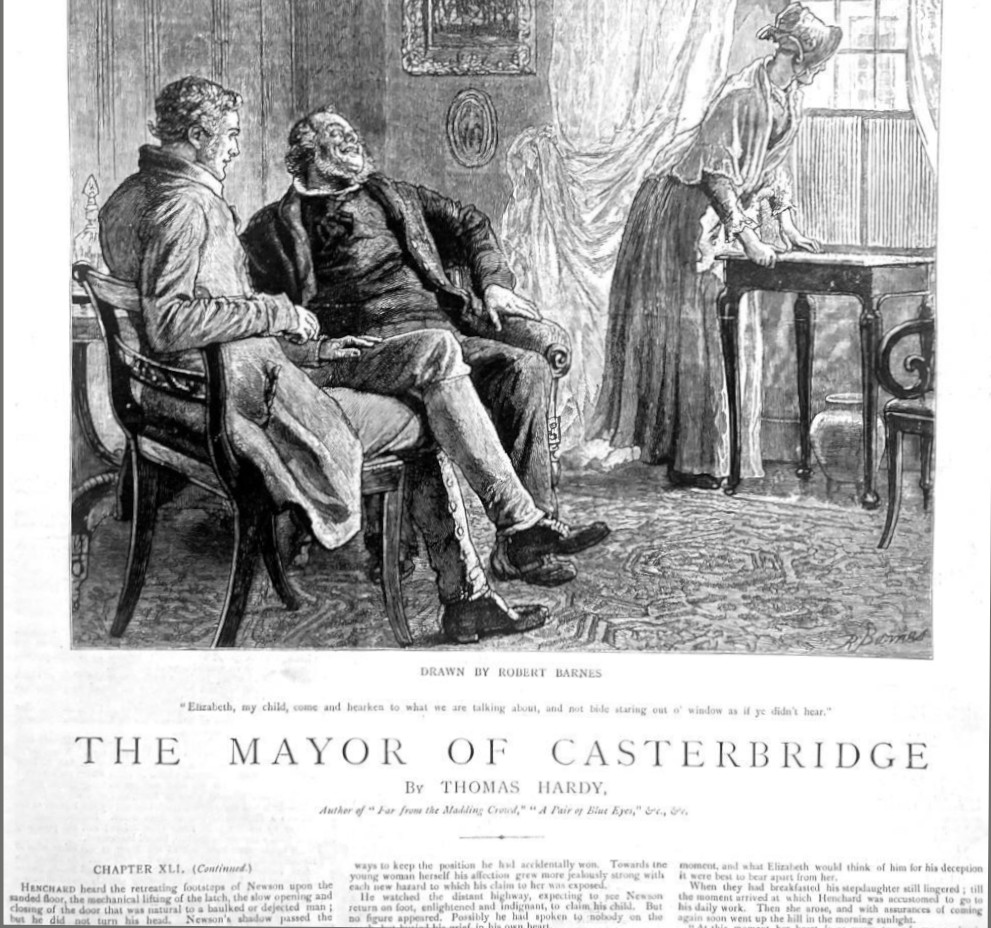

"Elizabeth, my child, come and hearken to what we are talking about and not bide staring out o' window as if ye didn't hear." by Robert Barnes. Plate 19, Thomas Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge, which appeared in the London The Graphic, 8 May 1886: Chapter XLI, p. 509. 17.4 cm high by 22.3 cm wide — 6 ⅝ inches high by 8 ⅞ inches wide. [Click on the image to enlarge it. See "Elizabeth, my child, come and hearken to what we are talking about and not bide staring out o' window as if ye didn't hear." for further commentary on the composition of the illustration.]

Passage Introduced by the Illustration: The Second Half of Chapter XLI

Henchard heard the retreating footsteps of Newson upon the sanded floor, the mechanical lifting of the latch, the slow opening and closing of the door that was natural to a baulked or dejected man; but he did not turn his head. Newson’s shadow passed the window. He was gone.

Then Henchard, scarcely believing the evidence of his senses, rose from his seat amazed at what he had done. It had been the impulse of a moment. The regard he had lately acquired for Elizabeth, the new-sprung hope of his loneliness that she would be to him a daughter of whom he could feel as proud as of the actual daughter she still believed herself to be, had been stimulated by the unexpected coming of Newson to a greedy exclusiveness in relation to her; so that the sudden prospect of her loss had caused him to speak mad lies like a child, in pure mockery of consequences. He had expected questions to close in round him, and unmask his fabrication in five minutes; yet such questioning had not come. But surely they would come; Newson’s departure could be but momentary; he would learn all by inquiries in the town; and return to curse him, and carry his last treasure away!

He hastily put on his hat, and went out in the direction that Newson had taken. Newson’s back was soon visible up the road, crossing Bull-stake. Henchard followed, and saw his visitor stop at the King’s Arms, where the morning coach which had brought him waited half-an-hour for another coach which crossed there. The coach Newson had come by was now about to move again. Newson mounted, his luggage was put in, and in a few minutes the vehicle disappeared with him.

He had not so much as turned his head. It was an act of simple faith in Henchard’s words — faith so simple as to be almost sublime. The young sailor who had taken Susan Henchard on the spur of the moment and on the faith of a glance at her face, more than twenty years before, was still living and acting under the form of the grizzled traveller who had taken Henchard’s words on trust so absolute as to shame him as he stood. gaze at some small object in the street. [Chapter XLI, p. 509 in serial]

Commentary: The Formatting of the Headnote Illustration and Captions in The Graphic

The "jovial sailor" who purchased Susan Henchard at the Weydon-Priors auction all those years before — Elizabeth-Jane's natural father — now returns, as if from the dead. Although he has returned just in time to displace Michael Henchard at Elizabeth-Jane's marriage to Farfrae, at the close of the eighteenth instalment it appears that Henchard has averted the displacement by convincing the middle-aged mariner that his wife and daughter are both dead. However, the nineteenth illustration immediately telegraphs that, somehow, in the forthcoming instalment Newson will be reunited with his natural daughter after all.

This is the second-to-the-last weekly illustration by Robert Barnes for the serialization of the 1886 Hardy novel. In the headnote episode, no. 19, Chapter Forty-one continues with Elisabeth’s father, “Captain” Newson, her new husband, and Elisabeth herself, not attending to the drawing room conversation, but looking anxiously out of the window to the street below. The story’s credentials are announced in varied type immediately below the illustration: THE MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE [large seriffed font, all capitals], BY THOMAS HARDY [much smaller seriffed font, still all capitals], and then a line that affirms Hardy’s status as the author of contemporary best-sellers: Author of “Far from the Madding Crowd,” “A Pair of Blue Eyes,” &c., &c. Chapter XLI (Continued). Henchard heard the retreating footsteps. . . .

Thus, the curtain opens with the departure of Newsome, in contradiction to the expectation created by the illustration. The serial reader is thus torn between hoping that Henchard has been able to maintain his relationship with his stepdaughter and that the girl will be reunited with her natural father before her wedding.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "A Consideration of Robert Barnes' Illustrations for Thomas Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge as Serialised in the London Graphic: 2 January-15 May, 1886." Victorian Periodicals Review 28, 1 (Spring 1995): pp. 27-39

Hardy, Thomas. The Mayor of Casterbridge. The Graphic 33 (8 May 1886): Instalment No. 19 (Chapters 41 [continued], 42, 43).

Hardy, Thomas. The Mayor of Casterbridge: A Story of a Man of Character. London: Osgood McIlvaine, 1895.

Jackson, Arlene. "The Mayor of Casterbridge: Realism and Metaphor."Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981. Pp. 96-104.

19 March 2025