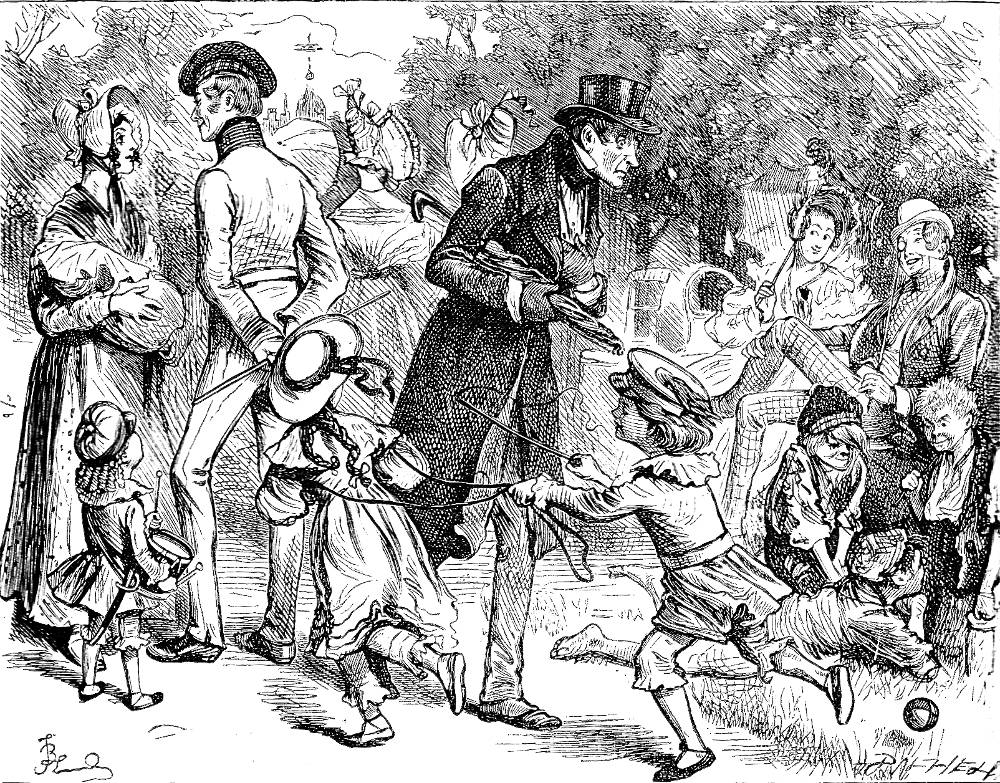

His spare pale face looking as if it were incapable of bearing the expression of curiosity or interest (wood-engraving). 1876. 10.5 cm high x 13.8 cm wide, framed (p. 104, placed in Chapter 2). Fred Barnard's realistic response to George Cruikshank's humorous description of the poor clerk, eating a solitary dinner, in the Second Series' copper-engraving for the first chapter in "Characters" in Sketches by Boz, Thoughts about People ["The Poor Clerk"], in which the social isolate's only companion is the newspaper.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

We were seated in the enclosure of St. James's Park the other day, when our attention was attracted by a man whom we immediately put down in our own mind as one of this class. He was a tall, thin, pale person, in a black coat, scanty gray trousers, little pinched-up gaiters, and brown beaver gloves. He had an umbrella in his hand — not for use, for the day was fine— but, evidently, because he always carried one to the office in the morning. He walked up and down before the little patch of grass on which the chairs are placed for hire, not as if he were doing it for pleasure or recreation, but as if it were a matter of compulsion, just as he would walk to the office every morning from the back settlements of Islington. It was Monday; he had escaped for four-and-twenty hours from the thraldom of the desk; and was walking here for exercise and amusement— perhaps for the first time in his life. We were inclined to think he had never had a holiday before, and that he did not know what to do with himself. Children were playing on the grass; groups of people were loitering about, chatting and laughing; but the man walked steadily up and down, unheeding and unheeded his spare, pale face looking as if it were incapable of bearing the expression of curiosity or interest.— "Characters," Chapter 1, "Thoughts about People," p. 101.

Commentary

Whereas Boz's emphasis had been on describing neighbourhoods, cityscapes, and businesses in "Scenes," in the third section of Sketches by 'Boz,' Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People (1836, 1839), in "Characters" Dickens focuses on the array of character types one might easily observe on the streets of London in the mid-1830s. This particular sketch, like the others in this section, does not quite amount to a short story since, although it has adequately developed setting and character, and focuses on what Edgar Allen Poe termed "a single, pre-conceived effect," it lacks both the requisite conflict and a rising action. Nevertheless, the sympathetic description of an emotional oyster is still of interest because it clearly anticipates Dickens's making the curmudgeonly Ebenezer Scrooge the protagonist in A Christmas Carol (1843).

In 'Thoughts About People' (Evening Chronicle, 23 April [1835]) Boz focuses on a solitary poor clerk wandering aimlessly in St. James's Park and extrapolates from his appearance and demeanour a whole existence of monotony; loneliness and privation — creates a character, in fact. It is a small-scale tour de force of the imagination. — Slater, "'The Copperfield Days': 1828-1835," p. 49.

The character sketch's original title in the Evening Chronicle was not particularly informative: "Sketches of London, No. 10." The sketch does not concern just the poor, friendless clerk who, oyster-like, lives an insulated existence (not unlike that of Nicolai Gogol's clerk in "The Overcoat") and, like Ebenezer Scrooge, in the original Cruikshank illustration awkwardly attempts to combine reading with eating to fill the void that opens before him when he leaves the office. Like Cruikshank, Barnard has chosen this "odd duck" in the park as his subject, rather than the other two men about whom the philosophical Boz expresses his sentiments in this sketch: the second man is deserving of our contempt, for, although far more affluent and a collector of books, he has no use for importunate young nephews who, having married, find themselves cash-strapped; and the third type, the London apprentice who struts through the streets in his coloured waistcoat on a Sunday afternoon, is merely callow, and will probably develop into quite a different sort of man. Young Dickens well well have seen these three types as possible future identities, were he not to escape his status as a legal clerk and parliamentary reporter.

Barnard's handling of the theme is interesting that he has juxtaposed the middle-aged, formally dressed clerk, his umbrella under his arm despite the manifestly pleasant weather, and happy families, in particular, an infant and six children, dashing about, chasing one another, and playing in the grass. Three fashionably dressed ladies and two middle-class, married men all offer a contrast to the gaunt clerk, who walks among them, but does not seem to see them. Barnard, then, has constructed the composition of bustling family life largely out of a single sentence: "Children were playing on the grass; groups of people were loitering about, chatting and laughing." Three of the children are fashionably dressed fledgling members of the bourgeoisie; three barefooted, ill-dressed working-class children — but they all represent the family life that the little clerk, trudging past them and oblivious to them, will never know. Thus, for all his sartorial correctness, the nameless clerk has nothing in life to look forward to.

References

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 159-162.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 345-347.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 101-103.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 204-208.

Dickens, Charles, and Fred Barnard. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Last modified 8 May 2017