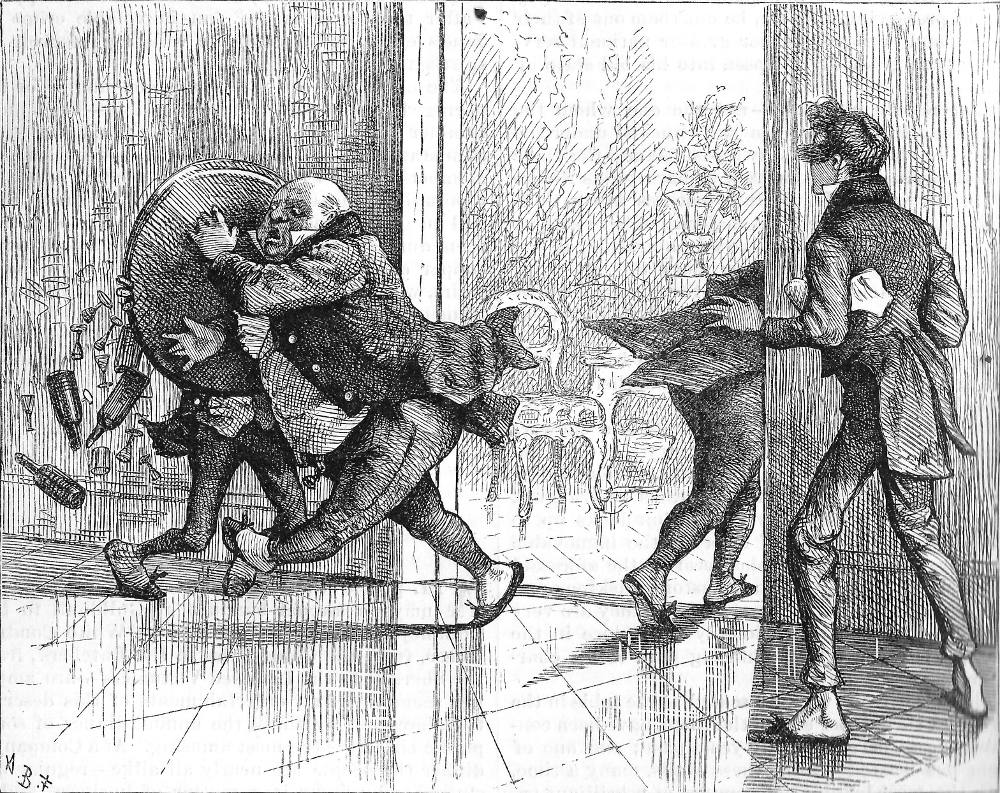

Tureens of soup are emptied with awful rapidity (wood-engraving) for "Public Dinners." 1876. 9.3 cm high x 13.7 cm wide, framed, on p. 80.

Passage Illustrated

The applause ceases, grace is said, the clatter of plates and dishes begins; and every one appears highly gratified, either with the presence of the distinguished visitors, or the commencement of the anxiously-expected dinner.

As to the dinner itself— the mere dinner — it goes off much the same everywhere. Tureens of soup are emptied with awful rapidity— waiters take plates of turbot away, to get lobster-sauce, and bring back plates of lobster-sauce without turbot; people who can carve poultry, are great fools if they own it, and people who can’t have no wish to learn. The knives and forks form a pleasing accompaniment to Auber’s music, and Auber’s music would form a pleasing accompaniment to the dinner, if you could hear anything besides the cymbals. The substantials disappear—moulds of jelly vanish like lightning— hearty eaters wipe their foreheads, and appear rather overcome by their recent exertions —people who have looked very cross hitherto, become remarkably bland, and ask you to take wine in the most friendly manner possible—old gentlemen direct your attention to the ladies’ gallery, and take great pains to impress you with the fact that the charity is always peculiarly favoured in this respect—every one appears disposed to become talkative — and the hum of conversation is loud and general. ["Public Dinners," 78]

Commentary

Barnard's twelfth illustration for Sketches by Boz, "Scenes," concerns the transition from the fish course to the soup in Chapter 19, "Public Dinners" — Tureens of soup are emptied with awful rapidity (p. 80). The illustration is unfortunately positioned in the following chapter ("The First of May"). Ironically, large upper-middle-class diners (including one resembling Samuel Pickwick) are voraciously consuming the multi-course banquet in honour of indigent and (presumably) starving orphans. The spirit of charity seems totally lacking in the speedy consumption of vast quantities of food and drink. The dubious waiter (centre right), who seems to be pondering a request from the diner to the right, has no correspondence with the text, but the large man consuming the soup corresponds to the diner beside "Fitz" — suggesting that Barnard is synthesizing two different moments in the essay:

Near him is a stout man in a white neckerchief and buff waistcoat, with shining dark hair, cut very short in front, and a great, round, healthy-looking face, on which he studiously preserves a half sentimental simper. Next him, again, is a large-headed man, with black hair and bushy whiskers; and opposite them are two or three others, one of whom is a little round-faced person, in a dress-stock and blue under-waistcoat. There is something peculiar in their air and manner, though you could hardly describe what it is; you cannot divest yourself of the idea that they have come for some other purpose than mere eating and drinking. [Chapter 19, 77]

Barnard's illustration must be read in part as a response to George Cruikshank's visual joke in the Second Series' copper-engraving in which Dickens, Cruikshank, the publishers Edward Chapman and and William Hall conduct "indigent orphans" into a charity banquet. in reaction, Barnard characteristically presents the public dinner realistically, with a waiter and a voracious, overfed bourgeois at the table. The original illustration for "Public Dinners," the nineteenth chapter in "Scenes" in Sketches by Boz, Second Series, bears the same title as the essay, Public Dinners (see below), in which the smirking writer and his illustrator, accompanied by their new publishers, marshall a procession of "indigent orphans" into the great dining chamber. The veteran illustrator's almost surrealistic joke requires that the reader have read the piece carefully prior to studying the Cruikshank plate, and, of course, recognize the much-reproduced figure of Boz, if not those of Cruikshank, Chapman, and Hall. No such analeptic reading is required to appreciate Barnard's study in excess middle-class consumption. The embedded joke that the viewer may not immediately comprehend involves the diner speaking behind his napkin to the attentive waiter, who looks directly out of the frame, as if scrutinizing the manners and behaviour of the "consumer" of the plate, that is, the reader.

Pertinent Illustrations in other editions: 1839, 1877, and 1910

Left: Cruikshank's original First Series illustration for the same sketch, with the Dickens, Cruikshank, Chapman, and Hall ushering in the "indigent orphans," Public Dinners (1839). Right: Harry Furniss's "Public Dinners": The Toast-Master (1910).

Above: A. B. Frost' farcical rendering of waiters in collision, Public Dinner: The Active Commission (1877), a scene that Dickens does not actually describe.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 19, "Public Dinners." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt. 1890, 120-125.

_____. "Scenes," Chapter 19, "Public Dinners." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876, 77-79.

_____. "Scenes," Chapter 19, "Public Dinners." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Thomas Nast and A. B. Frost. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877. 149-52.

_____. "Scenes," Chapter 19, "Public Dinners." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1, 154-159.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Created 6 April 2017

Last modified 24 February 2020