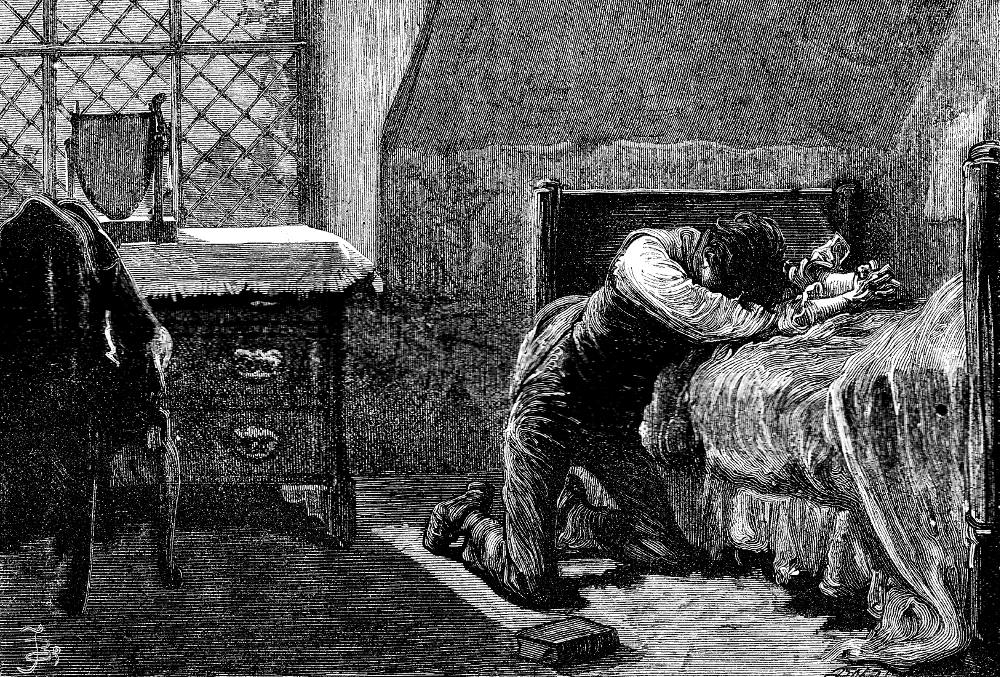

Fell upon his face in a passion of bitter grief, for Chap. XLIII; fortieth illustration for the British Household Edition, illustrated by Fred Barnard with fifty-nine composite woodblock engravings (1875). The framed illustration is 9.4 cm high by 13.7 cm wide (3 ¾ by 5 ⅜ inches), p. 288. Running head: "The Family Tea-Party" (285). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Ralph Nickleby breaks down

Hablot Knight Browne's depiction of the stolid money-lender upon his first appearance in the sequence: Mr. Ralph Nickleby's First Visit to His Poor Relations (April 1838), Chapter 3.

In short, it was a day of serene and tranquil happiness; and as we all have some bright day — many of us, let us hope, among a crowd of others — to which we revert with particular delight, so this one was often looked back to afterwards, as holding a conspicuous place in the calendar of those who shared it.

Was there one exception, and that one he who needed to have been most happy?

Who was that who, in the silence of his own chamber, sunk upon his knees to pray as his first friend had taught him, and folding his hands and stretching them wildly in the air, fell upon his face in a passion of bitter grief? [Chapter XLIII, "Officiates as a kind of Gentleman Usher, in bringing various People together," 286]

Commentary: Ralph Nickleby engaged in prayer?

Coming at the conclusion of a diverse chapter following the fortunes of a number of characters, and the introduction of handsome Frank Cheeryble to Kate Nickleby over a congenial family dinner table, this sharply contrasting closing paragraph for Chapter 43 and its subsequent realisation (positioned on the second page of the following chapter) shed light on Ralph Nickleby's subtle psychological makeup. Although he is derived from the usurious money-lender of Victorian melodrama and the wicked uncle of myth, legend, and fairytale, Ralph is apparently deeply conflicted owing to a Cain-and-Abel sibling rivalry with his older brother, Nicholas's virtuous father. Although earlier in the chapter he has embraced his villainy and been eagerly awaiting Sir Mulberry Hawk's rising from his sickbed to take vengeance on Nicholas, Ralph's alienation leads to deep self-pity and alienation. However, the neither the illustration nor the passage makes clear whether the alienated Ralph is succumbing to a crisis of conscience. The illustration therefore points towards some hidden grief and guilt later to be revealed.

That the setting is Ralph's bedroom the text establishes, but the reader is in doubt as to Ralph's genuinely engaging in prayer, although his posture certainly betokens "bitter grief." The logical question, of course, is "Grief over what?" Ralph has had a triumphant day, lording it over poorer customers and adopting a "familiar and jocose" demeanour with his more affluent business associates. But wealth does not apparently bring happiness, peace of mind, and fulfilment. The Bible that he has presumably been reading for spiritual consolation lies at his knee, and his folded hands suggest at least an attempt at prayer. But if he is not entreating Heaven for forgiveness in his treatment of his brother's family, what precisely has so disturbed Ralph that he should engage in such an activity and adopt such a posture. Nothing the readers have encountered in this chapter has prepared them for this scene. The room, however, is quite believable as it reflects both Ralph's somewhat Spartan tastes and middle-class affluence: a leaded-pane widow, a mirror, a linen runner and a noble chest-of-drawers all emphasize his character and social status, if not his harsh and forbidding nature.

Related material, including front matter and sketches, by other illustrators

- Nicholas Nickleby (homepage)

- Phiz's 38 monthly illustrations for the novel, April 1838-October 1839.

- Cover for monthly parts

- Charles Dickens by Daniel Maclise, engraved by Finden

- "Hush!" said Nicholas, laying his hand upon his shoulder. (Vol. 1, 1861)

- The Rehearsal (Vol. 2, 1861)

- "My son, sir, little Wackford. What do you think of him, sir?" (Vol. 3, 1861)

- Newman had caught up by the nozzle an old pair of bellows . . . (Vol. 4, 1861).

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 18 Illustrations for the Diamond Edition (1867)

- C. S. Reinhart's 52 Illustrations for the American Household Edution (1875)

- Harry Furniss's 29 illustrations for Nicholas Nickleby in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's four Player's Cigarette Cards (1910).

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Barnard, J. "Fred" (il.). Charles Dickens's Nicholas Nickleby, with fifty-nine illustrations. The Works of Charles Dickens: The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. XV. Rpt. 1890.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. With fifty-two illustrations by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1872. I.

__________. Nicholas Nickleby. With 39 illustrations by Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman & Hall, 1839.

__________. Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 4.

__________. "Nicholas Nickleby." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings by Fred Barnard et al.. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Created 12 September 20211