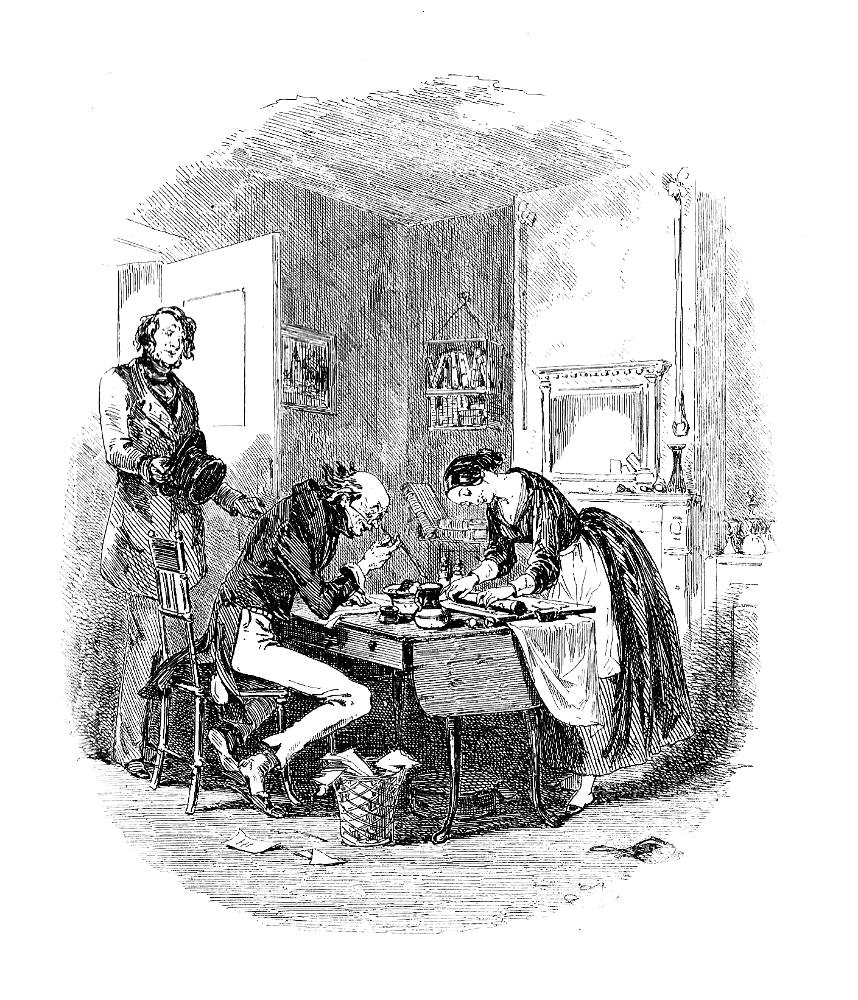

"No right!" cried the brass-and-copper founder. (1872). Forty-second illustration by Fred Barnard in the Household Edition for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Chapter XXXVI), page 289. [Here, Tom admonishes his sister's boorish, nouveau-riche employer for making Ruth's a poisoned working environment prior to giving notice on her behalf.] 10.6 x 13.7 cm, or 3 ¾ high by 5 ½ inches, framed, engraved by the Dalziels. Running head: “Tom Pinch's Blood Gets Up," 289. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Tom Confronts Ruth's Dictatorial Employer

"When you tell me," resumed Tom, who was not the less indignant for keeping himself quiet, "that my sister has no innate power of commanding the respect of your children, I must tell you it is not so; and that she has. She is as well bred, as well taught, as well qualified by nature to command respect, as any hirer of a governess you know. But when you place her at a disadvantage in reference to every servant in your house, how can you suppose, if you have the gift of common sense, that she is not in a tenfold worse position in reference to your daughters?"

"Pretty well! Upon my word," exclaimed the gentleman, "this is pretty well!"

"It is very ill, sir," said Tom. "It is very bad and mean, and wrong and cruel. Respect! I believe young people are quick enough to observe and imitate; and why or how should they respect whom no one else respects, and everybody slights? And very partial they must grow — oh, very partial! — to their studies, when they see to what a pass proficiency in those same tasks has brought their governess! Respect! Put anything the most deserving of respect before your daughters in the light in which you place her, and you will bring it down as low, no matter what it is!"

"You speak with extreme impertinence, young man," observed the gentleman.

"I speak without passion, but with extreme indignation and contempt for such a course of treatment, and for all who practise it," said Tom. "Why, how can you, as an honest gentleman, profess displeasure or surprise at your daughter telling my sister she is something beggarly and humble, when you are for ever telling her the same thing yourself in fifty plain, out-speaking ways, though not in words; and when your very porter and footman make the same delicate announcement to all comers? As to your suspicion and distrust of her: even of her word: if she is not above their reach, you have no right to employ her."

"No right!" cried the brass-and-copper founder.

"Distinctly not," Tom answered. "If you imagine that the payment of an annual sum of money gives it to you, you immensely exaggerate its power and value. Your money is the least part of your bargain in such a case. You may be punctual in that to half a second on the clock, and yet be Bankrupt. I have nothing more to say," said Tom, much flushed and flustered, now that it was over, "except to crave permission to stand in your garden until my sister is ready."

Not waiting to obtain it, Tom walked out. [Chapter XXXVI, "Tom Pinch Departs to Seek His Fortune. What He finds at Starting," 291. Running Head: "Tom Withdraws His Siste"]

Commentary

While Martin and Mark complete their American adventure by returning from the malarial swamps of Eden, Tom Pinch sets out for London from the Wiltshire village where he has served as Pecksniff's architectural apprentice for years. His destination is the Camberwell district of Southwark, south of the Thames, where his sister, Ruth, is a governess to the daughters of a wealthy industrialist. Discovering that his sister's employers are verbally abusive, demeaning in their attitude towards her, and unreasonable in their demands upon his sister Ruth, this new, assertive Tom dares to give the captain of industry a piece of his mind, and then to serve notice on his sister's behalf. Together they leave the upper-middle-class mansion, and take rooms in Islington, where Ruth becomes a model housekeeper, and Tom finds unexpected employment as the organizer and cataloguer of a private library. Significantly, he does not know who owns the library.

Although Fred Barnard in the 1872 Household Edition illustration attempts to realize the scene in which Tom visits his sister at Camberwell and finds her much put-upon by her insufferably arrogant and small-minded employer, Harry Furniss's version is much more dramatic, owing to his foregrounding the nouveau-riche family and putting the departing Pinches in the background as Tom delivers a Parthian shot. Ironically, despite its dramatic potential, Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, avoided the scene entirely, showing Tom's departure from Wiltshire by coach and then the Pinches in their Islington (village north of London) flat as John Westlock, formerly Tom's fellow apprentice and Ruth's future husband, pays an unexpected call. In the Barnard illustration, Tom wags an admonitory finger in the face of the surprised, overfed bourgeois as the employer's ugly wife and daughter look on (right). In the background, the fireplace, bric-a-brac on the mantelpiece, and richly embroidered tablecloth establish the setting as the family's parlour, and convey a sense of their shallow materialism. Clearly nobody has addressed the brass-and-copper founder in such critical terms as Barnard uses the occasion to demonstrate Tom's new-found assertiveness.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions, 1843-1924

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's realisation of Tom's departure by coach for London, Mr. Pinch Departs to Seek His Fortune (Chapter 36, February 1844). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s portrait of John Westlock and Ruth Pinch at Fountain Court, in the Inner Temple, London, John Westlock and Ruth Pinch (1867). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's realisation of John Westlock's arrival at Tom and Ruth Pinch's apartment, Mr. Pinch and Ruth Unconscious of a Visitor (Chapter 39, March 1844). Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 lithograph from pen-and-ink of Tom Pinch's astounding Ruth's employer with his candid appraisal of the family's unkindness towards his sister, Tom Pinch at the Brass and Copper Founder's(Chapter 39). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Barnard, Fred. Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vol. 2 of 4.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, with 59 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition, 22 volumes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2. [The copy of the Household Edition from which these pictures were scanned was the gift of George Gorniak, proprietor of The Dickens Magazine, whose subject for the fifth series, beginning in January 2008, was this 1843-44 novel.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 15: Martin Chuzzlewit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 267-294.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit: Fifty-nine Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-Six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. Mahoney, Charles Green, A. B. Frost, Gordon Thomson, J. McL. Ralston, H. French, E. G. Dalziel, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. Printed from the Original Woodblocks Engraved for "The Household Edition." London: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Pp. 185-216.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini; illustrated by Harold Copping. Character Sketches from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924.

Steig, Michael. "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Ch. 3, Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978. Pp. 51-85. [See e-text in Victorian Web.]

Steig, Michael. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz. Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

29 January 2008

Last modified 26 November 2024