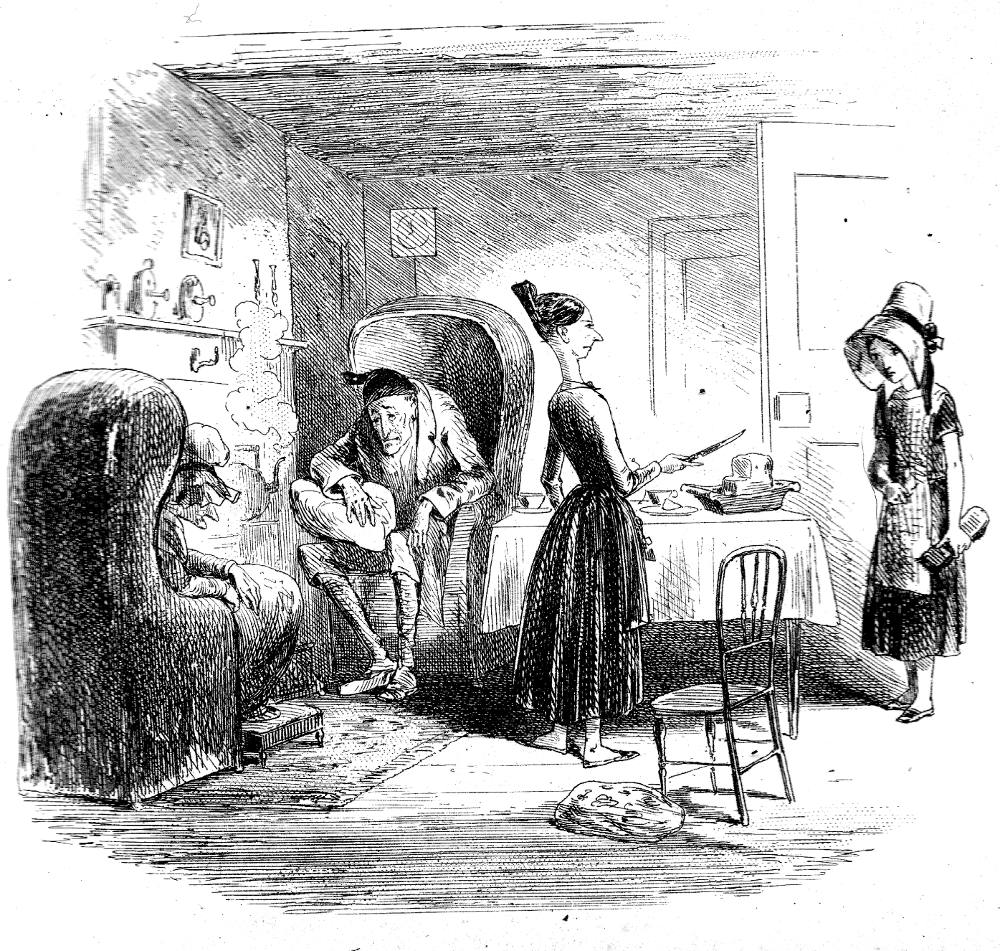

Grandfather Smallweed astonishes Mr. George — twenty-first illustration by Fred Barnard in the 9.4 cm high by 13.8 cm wide (3 11/16 by 5 ½ inches), framed, p. 141. Chapter 21. Running heads: "Mr. George" (149) and "About Captain Hawdon" (151). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Grandfather Smallweed leverages Trooper George's Debt

"I suppose you were an excellent son, Mr. George?" the old man hints with a leer.

The colour of Mr. George's face rather deepens as he replies, "Why no. I wasn't."

"I am astonished at it."

"So am I. I ought to have been a good son, and I think I meant to have been one. But I wasn't. I was a thundering bad son, that's the long and the short of it, and never was a credit to anybody."

"Surprising!" cries the old man.

"However," Mr. George resumes, "the less said about it, the better now. Come! You know the agreement. Always a pipe out of the two months' interest! (Bosh! It's all correct. You needn't be afraid to order the pipe. Here's the new bill, and here's the two months' interest-money, and a devil-and-all of a scrape it is to get it together in my business.)"

Mr. George sits, with his arms folded, consuming the family and the parlour while Grandfather Smallweed is assisted by Judy to two black leathern cases out of a locked bureau, in one of which he secures the document he has just received, and from the other takes another similar document which he hands to Mr. George, who twists it up for a pipelight. As the old man inspects, through his glasses, every up-stroke and down-stroke of both documents before he releases them from their leathern prison, and as he counts the money three times over and requires Judy to say every word she utters at least twice, and is as tremulously slow of speech and action as it is possible to be, this business is a long time in progress. When it is quite concluded, and not before, he disengages his ravenous eyes and fingers from it and answers Mr. George's last remark by saying, "Afraid to order the pipe? We are not so mercenary as that, sir. Judy, see directly to the pipe and the glass of cold brandy-and-water for Mr. George." [Chapter XXI, "The Smallweed Family," 149]

Commentary:Trooper George, His Loan from Smallweed, and his Backstory

Phiz's orginal serial illustration depicting the money-lender and his family prior to the arrival of Trooper George: The Smallweed Family (September 1852).

Part of the glue that binds the various subplots to the main plot of a Victorian novel is the backstories of such minor characters as Trooper George, the proprietor of a shooting gallery in Leicester Square. Since his business in London's entertainment centre is hardly booming, he can barely make the interest payments on his business loan from Grandfather Smallweed, a small-time loan-shark who, it turns out, is in league with the investigative attorney Tulkinghorn. The lawyer and his confederate are quite convinced that George Rouncewell can present them with a sample of the Nemo's handwriting, since before his descent into poverty and drug-addiction "Nemo" was Captain Hawdon, George's commanding officer. The writing sample would, Tulkinghorn expects, confirm the dead law-writer's true identity as Lady Dedlock'd lover. Thus, Tulkinghorn through Smallweed extorts the hapless Trooper George to obtain that hand-writing sample which will enable Tulkinghorn to blackmail Lady Dedlock.Barnard has effectively reakised Dickens's description of the affable retired soldier:

He is a swarthy brown man of fifty, well made, and good looking, with crisp dark hair, bright eyes, and a broad chest. His sinewy and powerful hands, as sunburnt as his face, have evidently been used to a pretty rough life. What is curious about him is that he sits forward on his chair as if he were, from long habit, allowing space for some dress or accoutrements that he has altogether laid aside. His step too is measured and heavy and would go well with a weighty clash and jingle of spurs. He is close-shaved now, but his mouth is set as if his upper lip had been for years familiar with a great moustache; and his manner of occasionally laying the open palm of his broad brown hand upon it is to the same effect. Altogether one might guess Mr. George to have been a trooper once upon a time. [Chapter XXI, "The Smallweed Family," 148]

In his treatment of the Smallweed family, Barnard in the Household Edition, unlike Phiz in the 1852-53 serialisation, gets to the point. In the 1873 edition Barnard does not describe the Smallweed family's dynamics and generational structure, but realisizes the scene in which the ruthless money-lender makes his demand of the hapless ex-soldier, of whose identity as Mrs. Rouncewell's younger son the readers are as yet unaware at this point. Dickens underscores at the beginning of the chapter how the unscrupulous Smallweed uses modest loans to create considerable profit: compound interest.

The father of this pleasant grandfather, of the neighbourhood of Mount Pleasant, was a horny-skinned, two-legged, money-getting species of spider who spun webs to catch unwary flies and retired into holes until they were entrapped. The name of this old pagan's god was Compound Interest. He lived for it, married it, died of it. Meeting with a heavy loss in an honest little enterprise in which all the loss was intended to have been on the other side, he broke something — something necessary to his existence, therefore it couldn't have been his heart — and made an end of his career. As his character was not good, and he had been bred at a charity school in a complete course, according to question and answer, of those ancient people the Amorites and Hittites, he was frequently quoted as an example of the failure of education.

His spirit shone through his son. . . . [Chapter XXI, 145]

Barnard's portrait of Grandfather Smallweed is so complete that he has included the money-lender's indispensable cushion at his feet, beside the overturned footstool: "Beside him is a spare cushion with which he is always provided in order that he may have something to throw at the venerable partner of his respected age whenever she makes an allusion to money a subject on which he is particularly sensitive" (145).

Other Illustrations of The Smallweeds' Parlour, 1867-1910

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 1867 Diamond Edition of the proletarian group: The Smallweed Family. Right: Harry Furniss's similar Charles Dickens Library Edition full-page lithograph of the extended family: The Smallweed Family (1910).

Related Material, including Other Illustrated Editions of Bleak House

- Bleak House (homepage)

- Phiz's Illustrations for Bleak House (March 1852 - September 1853)

- Sir John Gilbert's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 4, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Harry Furniss's Illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's five Player's Cigarette Cards, 1910

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

"Bleak House — Sixty-one Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vols. 1-4.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr, and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. VI.

_______. Bleak House, with 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. IV.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [28 original lithographs]. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Vol. 11. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_______. Bleak House, ed. Norman Page. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 18: Bleak House." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. XVII, 366-97.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70.

Created 5 March 2021