"Get the front door key."

Helen Paterson Allingham

March 1874

Wood-engraving

12.3 cm high by 10.5 cm wide (4 ⅞ by 4 ¼ inches), framed, in Chapter IX, page 256.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

"Get the front door key" in Chapters 9 ("The Homestead: A Visitor: Half-Confidences.") through 14 ("Effect of the Letter: Sunrise.") in Vol. 29: pages 257 through 279 (23.6 pages in instalment); plates: initial "B" (6.2 cm wide by 7.4 cm high) signed "H. P." left of centre at bottom margin and "'Get The Front-Door Key.' Liddy Fetched it." (facing page 257) horizontally-mounted, 10.4 cm wide by 15.9 cm high, signed "H. Paterson" in the lower-left corner. The wood-engraver responsible for this illustration was Joseph Swain (1820-1909), noted for his engravings of Sir John Tenniel's cartoons Punch. [Click on the image to enlarge it; mouse over links.]

Above: The initial-letter vignette and first full page of the third instalment of the story: B.

The March plate, depicting the old Wessex tradition of using a Bible and front door-key to predict the identity of a future spouse, advances the romantic plot both textually and pictorially. But a modern reader might be more interested in a scene showing Bathsheba's becoming her own bailiff as she settles accounts and offers bonuses to her farm-labourers in Chapter 10. In that scene, with the faithful Liddy by her side, she is wearing a "mourning dress" (p. 265, out of respect for her dead uncle) of "black silk" (p. 266), as in the plate. The theme of choice of marriage partners unites plate and vignette; however, in Hardy's letter-press the incident illustrated by the vignette precedes that illustrated by the full-page plate.

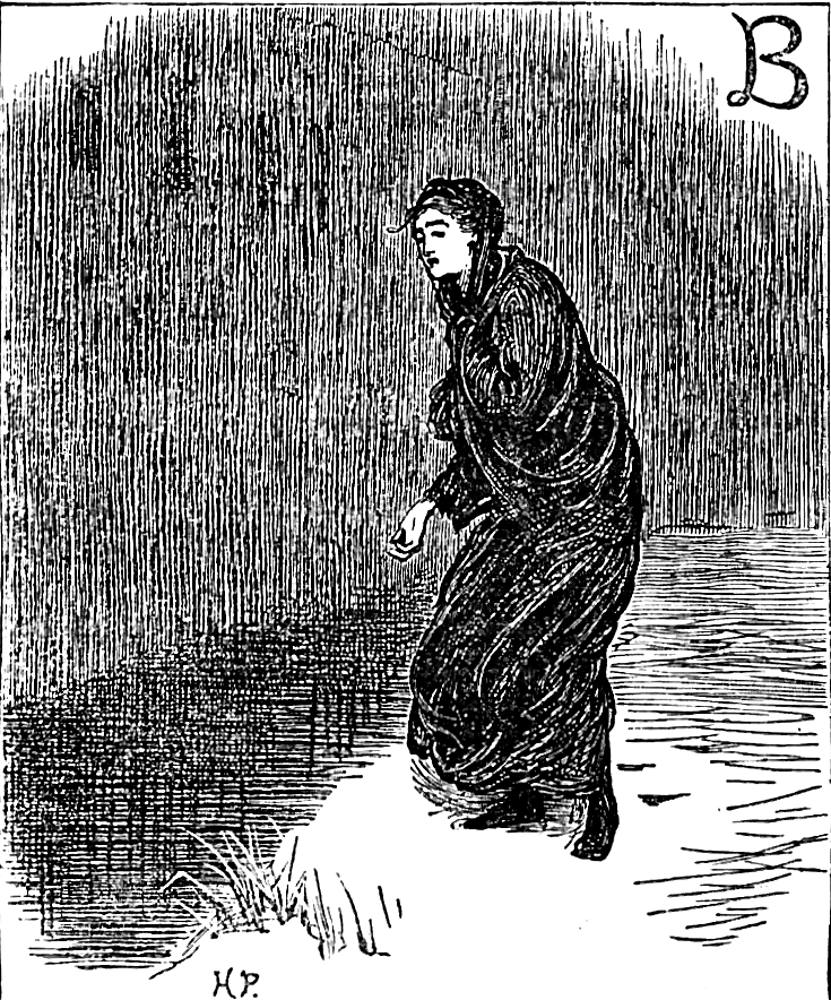

Having mysteriously vanished from Weatherbury, Fanny Robin cuts a pathetic figure in Paterson's vignette, which resembles traditional Roman mosaics of the spirit of winter: a thin, black-robed woman backed by a snowy landscape. In Paterson's vignette, the swirling draperies which enclose Fanny's gaunt form suggest both the sharpness of the wind and her inner turmoil. Outside the Melchester Barracks near the river, having followed the insensitive and arrogant young dandy she regards as her de facto husband from Casterbridge, the young servant, solitary and without friends, attempts to locate her lover's window. She stands in the freshly fallen snow, attempting to gain his attention by hurling a snowball at the fifth window in the barracks block. Ironically, her face resembles that of Bathsheba in the December plate -- such is the anguish that Frank Troy produces in the women who err by loving him, Paterson seems to imply. Subtly in the bleak background, four dark rectangular splotches suggest the windows. Slightly crouching, Fanny seems about to make an ineffectual throw, but her gaze is abstracted, as if some mental weight (such as the secret of her pregnancy) prevents her from concentrating on her target.

Opposite the vignette is another woman in black, but one in far more robust health who is surrounded by all the appurtenances of a proper Victorian parlour: a maid, an ornately carved piano with piles of sheet music on top, a china cabinet, a linen-draped table, a footstool, an oval portrait (or, perhaps, by this point in the 19th c., a daguerreotype), carpeting, and wainscoting (none of which details but the "new" old piano on page 273 has Hardy supplied). A further physical connection between the figures of Bathsheba (standing straight, a head taller than her companion) and Fanny (somewhat hunched over) is that both are turned slightly to the right and framed by an appropriate backdrop. Shortly, the two, unbeknownst to each other, will become rivals in Troy's affections. By the time that the reader of The Cornhill encounters the Bible-and-key scene in the letter-press, he or she has already observed Bathsheba holding her own at grain bargaining in the patriarchal bastion of the Casterbridge Corn Exchange.

Having been so pointedly ignored by her neighbour, Farmer Boldwood, there, she had been at once put out and fascinated; no wonder then that she readily accedes shortly afterwards to Liddy's proposal that "by means of the Bible and key" (p. 274) they attempt to discover whom she is fated to marry. Educated to be a governess and equipped with a scientific rationalism that derides such folk practices as mere superstition, Bathsheba pronounces the time-honoured procedure "Nonsense," but as a romantic at heart overrides her companion's objections about trying such an experiment on a Sunday. Thus, once again does sentiment negate reason in Bathsheba's conduct. The plate's caption does not accord with the young women's actions in that they are already in the act of turning the book around by the key, so that Helen Allingham is attempting to show motivation and consequent action at one time. Furthermore, Paterson's Bathsheba seems serious rather than guilty: unlike her letter-press counterpart, she is neither blushing, nor thrilled, nor abashed. Indeed, the dominant impression one receives of Bathsheba in the plate is of her quizzical look of concentration, rather than the kind of awkward self-consciousness that Hardy describes.

Bibliography

The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy. Volume One: 1840-1892; Volume Three: 1903-1908, ed. Richard Little Purdy and Michael Millgate. Oxford: Clarendon, 1978, 1982.

Hardie, Martin. Water-colour Painting in Britain, Vol. 3: The Victorian Period, ed. Dudley Snelgrove, Jonathan Mayne, and Basil Taylor. London: B. T. Batsford, 1968.

Hardy, Thomas. Far From the Madding Crowd. With illustrations by Helen Paterson Allingham. The Cornhill Magazine. Vols. XXIX and XXX. Ed. Leslie Stephen. London: Smith, Elder, January through December, 1874.

Holme, Brian. The Kate Greenaway Book. Toronto: Macmillan Canada, 1976.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Turner, Paul. The Life of Thomas Hardy: A Critical Biography. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998, 2001.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Helen

Allingham

Thomas

Hardy

Next

Created 12 December 2001 Last updated 22 October 2022