"A gentleman attired in mourning, and cloaked and booted like a rider on horseback, who stood at the bar-door." by E. A. Abbey. 10.2 x 13.4 cm framed. From the Household Edition (1876) of Dickens's Christmas Stories, p. 134. Dickens's The Battle of Life: A Love Story was first published for Christmas 1846. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Signed conspicuously in the lower right corner, Abbey's final illustration for The Battle of Life resolves the story's mysterious disappearance of Marion Jeddler by clarifying the fact that Michael Warden was in no way involved in it; this scene has a comic counterpart in the British Household Edition wood-engravings by Fred Barnard, who depicts Benjamin Britain and his wife Clemency in the parlour of the Nutmeg Grater Inn, where a tanned, fit-looking stranger has alighted from his horse and stands with his back towards the publican and his wife, seeking news of the Jeddlers. As a domestic melodrama, the novella requires the antiphonal comic note provided by the quirky Jeddler servants, Benjamin being the stock type known as the Comic Man and Clemency the Comic Woman of the melodrama, whose class, topics of conversation, and mode of dress contrast those of the principal, bourgeois characters. Unlike Barnard, Abbey elects to take the moment seriously, emphasizing the element of suspense instead of the character comedy.

Abbey's illustration compared to plates by Clarkson Stanfield and Fred Barnard.

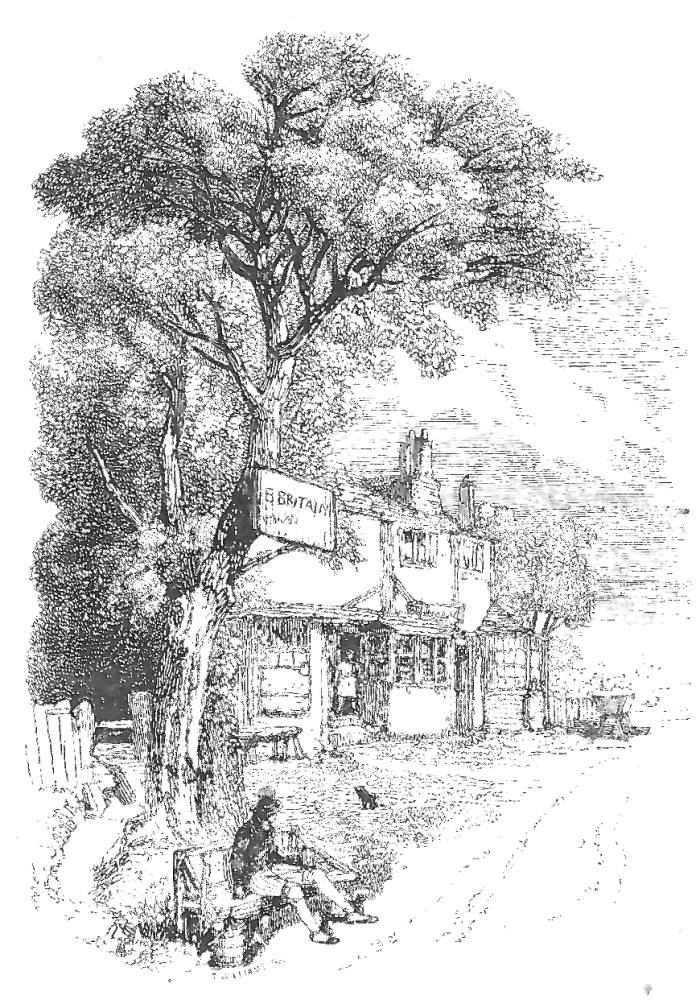

Left: Fred Barnard's comic handling of the scene, "Guessed half aloud 'milk and water,' 'monthly warning,' 'mice and walnuts' — and couldn't approach her meaning." with Benjamin and Clemency looking curiously at the stranger (1878); right: Clarkson Stanfield's "The Nutmeg Grater", in which an idler is sunning himself under an oak while the publican stands at open door (1846). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

These plates represent two alternate interpretations of the return of Michael Warden, six years after events at the end of "Part the Second." Right: Clarkson Stanfield's "The Nutmeg Grater". Left: Fred Barnard's "Guessed half aloud 'milk and water,' 'monthly warning,' 'mice and walnuts' — and couldn't approach her meaning."

Although Dickens had asked his London agent, John Forster, to make the decision about "having coats and gowns of dear old Goldsmith's day" (cited in Gibson, 43) to enhance the visual element, a certain "picturesqueness" may be found in the scenes involving an architectural or natural backdrop. Although Stanfield has provided a fine architectural study that sounds the Wordsworthian note by conveying the nobility of those who live close to nature, the quaint study of a roadside inn does little to pique the reader's curiosity. There is little such "picturesqueness" in the Barnard and Abbey Household Edition illustrations, which tend instead to focus on the chief characters, but here give their due to Benjamin Britain and Clemency Newcome. Instead of showing the quaint exterior and lovely physical setting of the roadside inn as Clarkson Stanfield has done in the original volume, for example, Barnard has moved the reader inside the village public house to witness Britain's puzzlement at his wife's attempting to tell him sotto voce that their visitor is none other than squire Michael Warden, last seen in Leech's "The Night of the Return" in the original volume (even though, in fact, he was not present just before midnight to assist Marion in her escape) and consulting with Snitchey and Craggs about how to repair his fortunes in the two Household Edition illustrations, Barnard's and Abbey's. The scene, set six years after events of the previous chapter, begins with Warden's arrival on horseback about tea time (late afternoon); as Dickens wished to maintain some suspense as to the visitor's identity, he narrates the scene from the perspective of the publicans and designates Warden "the stranger" throughout until Clemency suddenly makes the connection, but fails to communicate to her husband in a whisper:

Passage Illustrated:

She raised her head as with a sudden attention to the circumstances under which she was recalling these events, and looked quickly at the stranger. Seeing that his face was turned toward the window, and that he seemed intent upon the prospect, she made some eager signs to her husband, and pointed to the bill, and moved her mouth as if she were repeating with great energy, one word or phrase to him over and over again. As she uttered no sound, and as her dumb motions like most of her gestures were of a very extraordinary kind, this unintelligible conduct reduced Mr. Britain to the confines of despair. He stared at the table, at the stranger, at the spoons, at his wife — followed her pantomime with looks of deep amazement and perplexity — asked in the same language, was it property in danger, was it he in danger, was it she — answered her signals with other signals expressive of the deepest distress and confusion — followed the motions of her lips — guessed half aloud "milk and water," "monthly warning," "mice and walnuts" — and couldn't approach her meaning. ["Part The Third," The Household Edition: by Chapman & Hall, p. 148; by Harper & Bros., p. 135]

In the entirely new series of illustrations for the fourth Christmas Book, both Abbey and Barnard chose to do more than describe the quaint exterior of Benjamin and Clemency's roadside inn, the subject of marine and landscape painter Stanfield's third and final contribution to the original programme.

His facade for 'The Nutmeg-Grater' inn where Warden reappears to solve the mystery of Marion's disappearance six years earlier, is suitably picturesque and visually reinforces the accompanying nostalgic verbal description. . . . [Cohen, 181]

Both Household Edition plates capture the striking moment when Warden returns to clear up for the reader the peculiar circumstances surrounding Marion's supposed "elopement," but Barnard's illustration involves considerably more humour as he places Clemency, struggling to make herself understood, at the centre of the composition, relegating Warden to a half-seen figure in the doorway to the bar-room (upper left). On the other hand, Abbey makes the rider, just alighted from his horse (upper right), the focal point of his final illustration for the novella, framing him in the open doorway, and throwing him into a slight shadow against the brightness of the outdoors behind him. Whereas both Household Edition illustrators show Benjamin Britain in profile, Barnard gives much greater prominence to the speculative Clemency, as is appropriate since her speech is the essence of the caption. She speaks softly, behind her hand, so that the stranger will not overhear their conversation about his identity. Visual continuity suffers somewhat, however, as this Clemency does not much resemble the character opening the door to Alfred Heathfield in the previous illustration. Whereas Abbey's costuming of the figures is still solidly mid-eighteenth century (note Benjamin's wig, for example), in Barnard's version Warden's riding coat and hat, both similar to Alfred's in Barnard's previous illustration, imply a late eighteenth-century setting. Barnard, too, has more effectively realised the space (identified as the interior of a public-house by the tally-slate above Clemency) in which the publicans deal with the visitor, for Abbey's booted-and-caped rider is standing at the couple's parlour door and not, as the text suggests, in the bar-room.

Whereas Barnard elects to put Warden in late-eighteenth-century fashions, as exemplified by his hat and topcoat, Abbey has dressed his mysterious rider in the manner of the mid-eighteenth century, with ticornered hat, cloak, and topboots. Abbey even clarifies the stranger's mode of travel by offering the reader a glimpse of the horse, tied to a post (upper right). Normally Abbey does not offer much background detail, but here he includes a number of details to establish the public-house setting: a keg, bottles, pitcher, and bowl (left), as well as a small plant on the window-sill (upper centre). Abbey captures the precise moment when Britain grips the arm of his chair and turns to address the stranger.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Il. John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

James, Henry. Picture and Text. New York: Harper and Bros, 1893. Pp. 44-60.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 27 December 2012