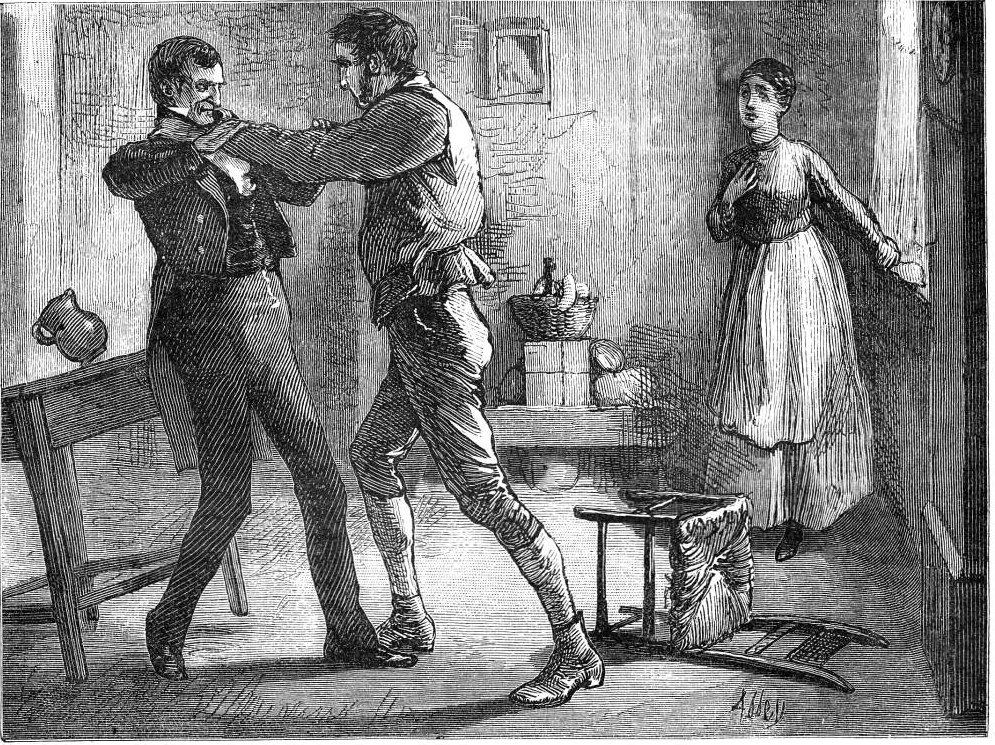

"'Listen to me!' he said. 'And take care that you hear me right'." by E. A. Abbey. 10 x 13.4 cm framed. From the Household Edition (1876) of Dickens's Christmas Stories, p. 101. Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home was first published for Christmas 1845. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The Barnard and Abbey Household Edition illustrations reify the central issue of The Cricket on the Hearth: in a confusion typical of domestic melodrama, is John Peerybingle's misinterpretation of this scene in the "ware-room" or storeroom of Tackleton's toy manufactory about to result in the husband's murdering his young wife and her putative lover? The shotgun posed near John in Doyle's and Leech's illustrations suggest the possibility of violent action. Seeing his wife with a handsome youth, the supposed elderly stranger to whom he earlier gave a ride in his carrier's van, John incorrectly concludes that his wife is guilty of adultery. Acting the role of Satanic tempter, the misanthropic Tackleton seems to feel that showing John such a sight will prompt him to violence, but John surprises him by refusing to exact vengeance.

Here, in Abbey's rather more dramatic or melodramatic scene, blaming himself for having initiated an unequal marriage, John vents his anger and frustration on Tackleton himself. In contrast, the illustrators of the 1845 edition chose to show the consequences of this disclosure of apparent adultery. In "Chirp the Third", Richard Doyle shows an anguished husband, alienated but surrounded by domestic fairies, wrestling emotionally before the hearth with his feelings of rejection and betrayal. The Leech reiteration of this scene in "John's Reverie" underscores the significance of this narrative moment, which is preceded by this altercation between the tempter, Tackleton, and the tempted, John Peerybingle:

"Did I consider," said the Carrier, "that I took her — at her age, and with her beauty — from her young companion, and the many scenes of which she was the ornament; in which she was the brightest little star that ever shone, to shut her up from day to day in my dull house, and keep my tedious company? Did I consider how little suited I was to her sprightly humor, and how wearisome a plodding man like me must be, to one of her quick spirit? Did I consider that it was no merit in me, or claim in me, that I loved her, when everybody must, who knew her? Never. I took advantage of her hopeful nature and her cheerful disposition; and I married her. I wish I never had! For her sake; not for mine!"

The Toy-merchant gazed at him, without winking. Even the half-shut eye was open now.

"Heaven bless her!" said the Carrier, "for the cheerful constancy with which she tried to keep the knowledge of this from me! And Heaven help me, that, in my slow mind, I have not found it out before! Poor child! Poor Dot! I not to find it out, who have seen her eyes fill with tears, when such a marriage as our own was spoken of! I, who have seen the secret trembling on her lips a hundred times, and never suspected it till last night! Poor girl! That I could ever hope she would be fond of me! That I could ever believe she was!"

"She made a show of it," said Tackleton. "She made such a show of it, that to tell you the truth it was the origin of my misgivings."

And here he asserted the superiority of May Fielding, who certainly made no sort of show of being fond of him.

"She has tried,' said the poor Carrier, with greater emotion than he had exhibited yet; "I only now begin to know how hard she has tried, to be my dutiful and zealous wife. How good she has been; how much she has done; how brave and strong a heart she has; let the happiness I have known under this roof bear witness! It will be some help and comfort to me, when I am here alone."

"Here alone?" said Tackleton. "Oh! Then you do mean to take some notice of this?"

"I mean," returned the Carrier, "to do her the greatest kindness, and make her the best reparation, in my power. I can release her from the daily pain of an unequal marriage, and the struggle to conceal it. She shall be as free as I can render her."

"Make her reparation!" exclaimed Tackleton, twisting and turning his great ears with his hands. "There must be something wrong here. You didn't say that, of course."

The Carrier set his grip upon the collar of the Toy-merchant, and shook him like a reed.

"Listen to me!" he said. "And take care that you hear me right. Listen to me. Do I speak plainly?"

"Very plainly indeed," answered Tackleton. ["Chirp the Third," p. 100]

Other illustrators' portrayals of Tackleton

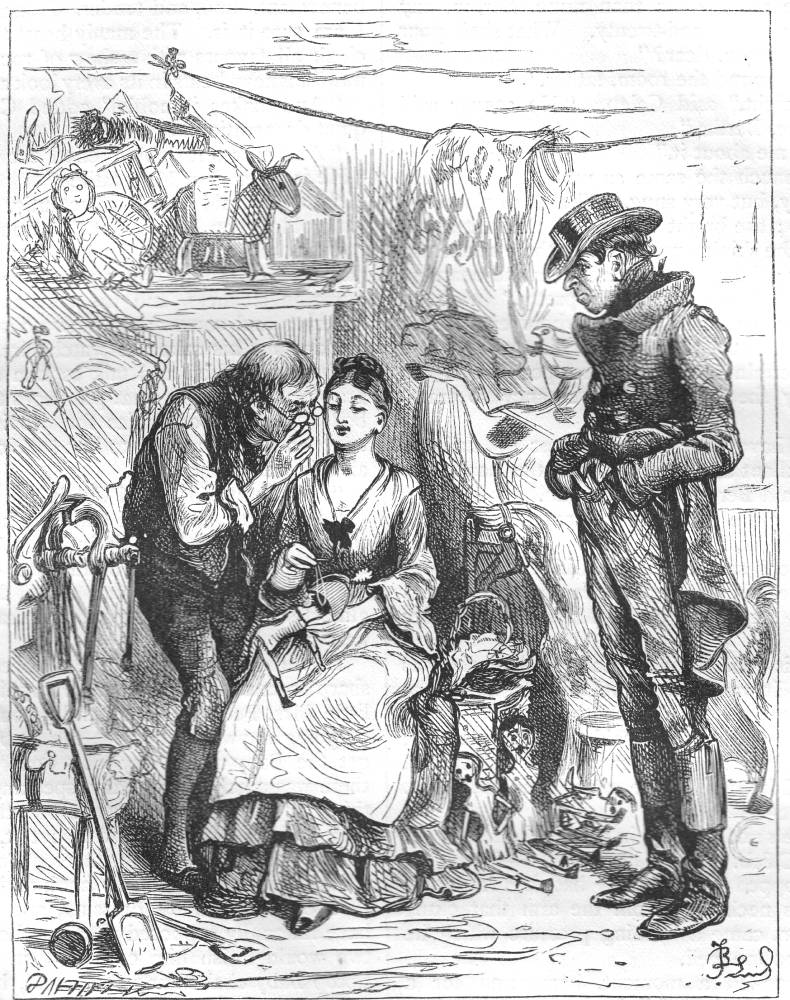

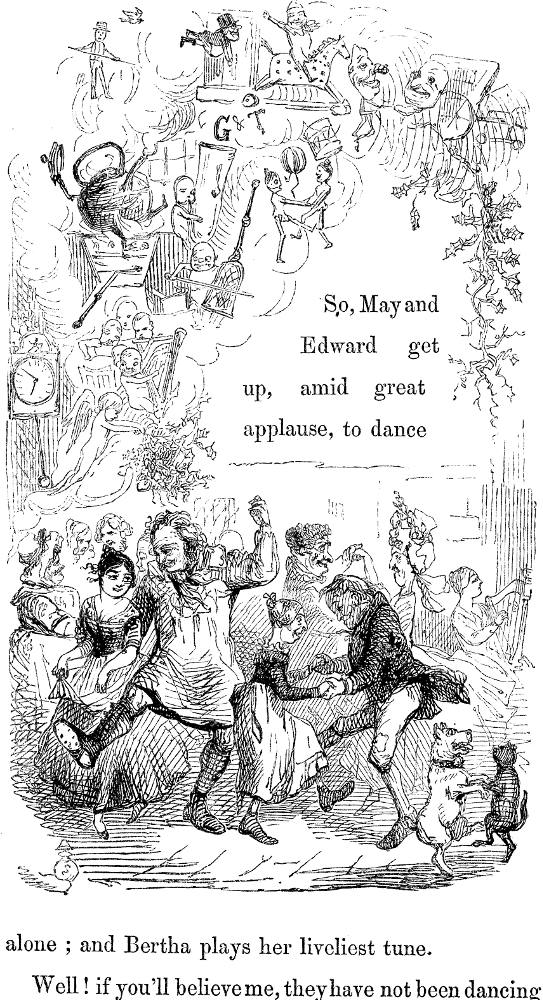

Left: Fred Barnard's Tackleton, detail (1878); right, John Leech's "The Dance," Tackleton and Mrs. Fielding (background) (1845).

The Enigmatic Figure of Tackleton, The Tempter

There is more than a whiff of Brimstone about Tackleton, the sarcastic and unsympathetic employer who reprises the initial persona of Ebenezer Scrooge in the first of the Christmas Books. Appealing to the Victorian social conscience in the second of the series, The Chimes (1844), Dickens found himself with no shortage of Benthamite and Malthusian villains — Alderman Cute, Sir Joseph Bowley, and the statistician Filer all admirably represent the forces opposed to improving the lot of the working class. However, since he had decided to abandon such controversial issues as prostitution and incendiarism in the third of the series, Dickens found himself short of villainous material, in spite of having an admirable lower-middle-class protagonist, John Peerybingle.

Incidental to the main plot issue — Dot's supposed adultery with the old stranger who is in fact a handsome youth in disguise — is the matter of Tackleton's forcing an engagement upon May Fielding, who has been pining for her sailor-lover lost at sea, Edward Plummer. With Edward's sister and father, the toy-makers Bertha and Caleb Plummer, he reveals himself to be a somewhat callous employer who disregards the welfare of his employees in order to turn a profit. However, Dickens's portrait of an exploitative capitalist falls short of his detailing the vices of the miser of the 'Change, Ebenezer Scrooge. That Tackleton's gruffness is but superficial is implied in the ease with which (without much motivation) he experiences a change of heart in the final scene and is welcomed back into the community at festival.

The original illustrators — Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Edwin Landseer, and Clarkson Stanfield — apparently were not inspired by the sardonic capitalist, who appears briefly in just the final illustration, "The Dance" by John Leech. A curmudgeon without conviction, a mere plot device and "domestic ogre, who had been living on children all his life, and was their implacable enemy" ("Chirp the First," p. 83 in the American Household Edition), Tackleton is a pasteboard villain, as undeveloped and one-dimensional as the blocking figures of pantomime — or nearly so.

Tackleton the Toy-merchant, pretty generally known as Gruff and Tackleton — for that was the firm, though Gruff had been bought out long ago; only leaving his name, and as some said his nature, according to its Dictionary meaning, in the business — Tackleton the Toy-merchant, was a man whose vocation had been quite misunderstood by his Parents and Guardians. If they had made him a Money Lender, or a sharp Attorney, or a Sheriff's Officer, or a Broker, he might have sown his discontented oats in his youth, and, after having had the full run of himself in ill-natured transactions, might have turned out amiable, at last, for the sake of a little freshness and novelty. But, cramped and chafing in the peaceable pursuit of toy-making, he was a domestic Ogre, who had been living on children all his life, and was their implacable enemy. He despised all toys; wouldn't have bought one for the world; delighted, in his malice, to insinuate grim expressions into the faces of brown-paper farmers who drove pigs to market, bellmen who advertised lost lawyers' consciences, movable old ladies who darned stockings or carved pies; and other like samples of his stock in trade. In appalling masks; hideous, hairy, red-eyed Jacks in Boxes; Vampire Kites; demoniacal Tumblers who wouldn't lie down, and were perpetually flying forward, to stare infants out of countenance; his soul perfectly revelled. They were his only relief, and safety-valve. He was great in such inventions. Anything suggestive of a Pony-nightmare was delicious to him. He had even lost money (and he took to that toy very kindly) by getting up Goblin slides for magic-lanterns, whereon the Powers of Darkness were depicted as a sort of supernatural shell-fish, with human faces. In intensifying the portraiture of Giants, he had sunk quite a little capital; and, though no painter himself, he could indicate, for the instruction of his artists, with a piece of chalk, a certain furtive leer for the countenances of those monsters, which was safe to destroy the peace of mind of any young gentleman between the ages of six and eleven, for the whole Christmas or Midsummer Vacation. ["Chirp the First," p. 83]

In the scene with John after he has revealed to the doting middle-aged husband what looks like adultery, Tackleton momentarily assumes the role of Shakespeare's Iago, the jealous, satanic tempter, to John's Othello, as he pushes John towards violence against the youth who seems to have captured Dot's heart. John's capacity for both self-blame and forgiveness thwarts Tackleton's evil designs. Appropriately, Leech depicts him well in the background of the final illustration, dancing with the elderly Mrs. Fielding, perhaps to underscore the unsuitability of his putative match with May. However, both Household illustrators, E. A. Abbey and Fred Barnard, have taken a greater degree of interest in the enigmatic would-be villain of the piece; whereas Barnard treats Tackleton with detached humour in the scene in which Bertha extols him as a kind and caring employer, Abbey interprets him as a slender, fashionably-dressed gentleman who serves in his malice as John's alter ego. Despite the fact that the powerful carrier is gripping him by the throat, Abbey's Tackleton is unperturbed. Of John's height and build, Tackleton in Abbey's final cut for The Cricket on the Hearth even resembles his assailant facially, and exhibits considerable self-control as he unflinchingly stares his adversary in the eye. The tipping table and overturned chair imply the chaos into which Tackleton is attempting to throw John's domestic establishment as Dot cowers in the corner, her look and gesture of concern enforcing the reader to believe that the altercation may well result in bodily harm, if not in the death of the toy manufacturer.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home. Il. John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edwin Landseer. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1845.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 17 December 2012