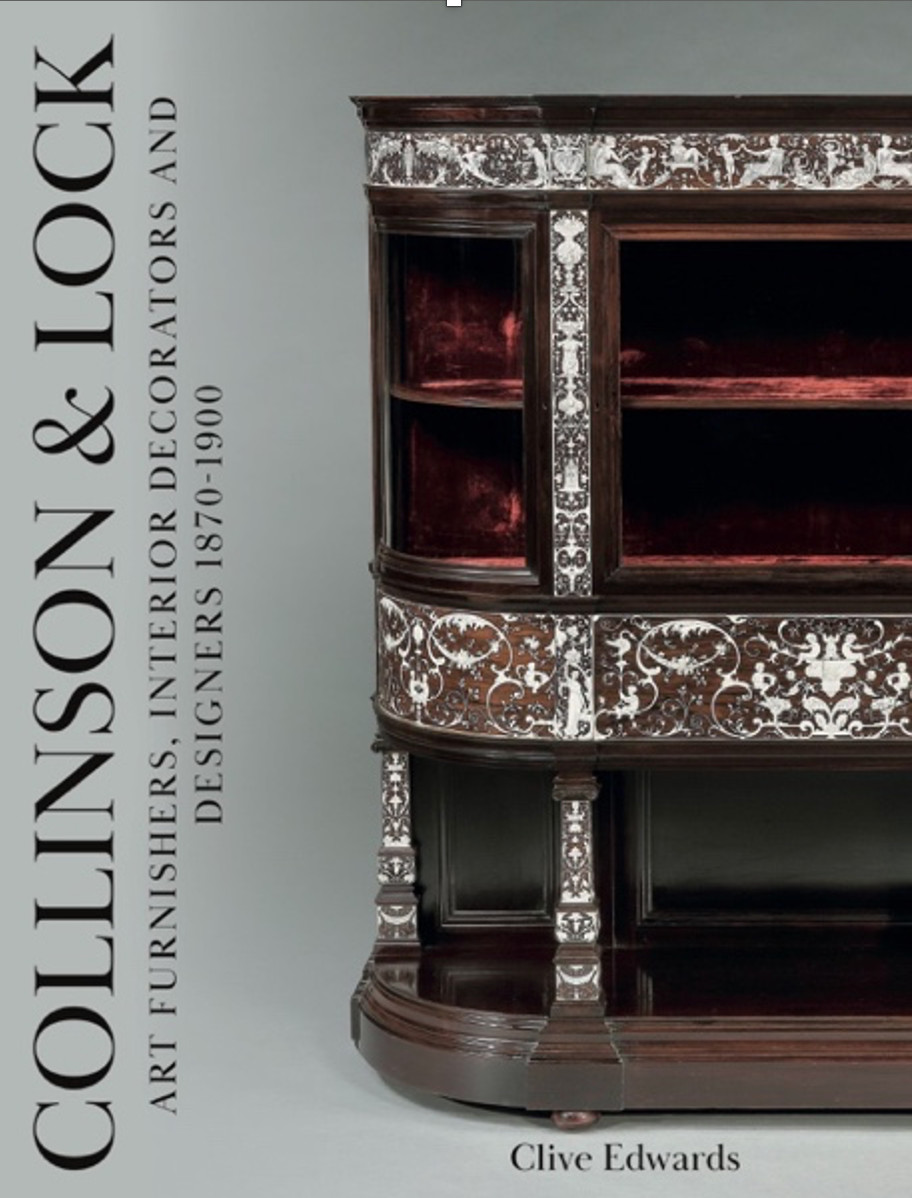

Professor Edwards has kindly allowed us to include an excerpt from his new book, Collinson and Lock: Art Furnishers, Interior Decorators and Designers, 1870-1900 (Troubador, 2022) on our website. The excerpt comes from the first chapter, pp. 11-14, and explains the controversies about art furniture in the second half of the Victorian period. The issues raised here are fully discussed later in the book, which, of course, focuses on Collinson & Lock itself. The excerpt has been formatted, illustrated from our own website, and linked by Jacqueline Banerjee. Please note that the book itself is handsomely illustrated.

Art, Architecture and Design

ne of the most important features of superior art furniture was the employment of architects/designers by furniture manufacturers, which represented the return of a practice that had appeared to lapse for much of the first half of the nineteenth century. Following the apparently widespread abrogation of responsibility for interior decoration and furniture design by architects early in the nineteenth century, certain retail furnishers and decorators, in their role as middlemen within a creative economy, acted as coordinators of interior design projects and crucially had overall responsibility and control of the works undertaken. Although some architects such as A. W. N. Pugin and William Burges designed complete buildings, interiors and their furnishings, the anonymous author of an 1847 article entitled "The Architect versus the Cabinet Maker and Others" summed up the issue. “There cannot be refused to the man of taste [i.e., architect], when he looks on his Architectural-work marred and distracted by the wretched Decorator or Upholsterer, the justice of his complaint that the Decorator or Upholsterer ought to be at least his subjects, if not practically,as regards design, incorporated in himself" (228).

Left: Cabinet by William Burges, 1858. Right: Gothic Revival Settle, after a design by Pugin.

There were clearly issues around the employment of eminent architects and the lack of designer training within the trade, as Matthew Wyatt explained in 1856: "The principal impediments to the progress of the manufacture of elegant cabinetmaker’s work in this country are caused by a great want of designers, draughtsmen, and modellers; in fact, of all the directors of art. The very few who can assist, demand and are paid such excessive rates, that their services are dispensed with, except upon important occasions" (311).

There was no doubt a considerable problem, not only with roles, but also with the question of appropriate taste and education. Indeed, the professional journals often harked back to the past, lamenting the architect’s loss of control over interior design work. In 1863, The Builder, a journal for architects, forcefully argued that: “Every opportunity should be taken to demonstrate the importance of interior decoration as a subject for the attention of architects themselves. All decoration is part of architecture; coloured decoration is predominantly concerned in the effect of most interiors; and architects should never have allowed the study and control of it to escape them” (“The Architectural Exhibition,” p. 237).

Five years later, Charles Eastlake weighed into the discussion and concluded that things were changing.

Fifty years ago, an architect would probably have considered it beneath his dignity to give attention to the details of cabinet-work, upholstery, and decorative painting. But I believe there are many now, especially among the younger members of the profession, who would readily accept commissions for such supervision if they were adequately remunerative, and that they might become so is evident from the fact that the furniture of a new house frequently costs as much if not more than the house itself: And when clients lead the way, we may be sure that manufacturers will seek assistance from the same source. [x]

The reality was a lot more complex than this suggests, but there was clearly a schism between the designing of architectural shells and the interior that has still not been fully resolved. The firm of Collinson & Lock took the same view (see Allison C. White, for example). In any event, it is evident that the control of work for the design of furniture, furnishings and interiors had generally moved away from the architects’ direct control to other parties. In 1868, Building News, in an article entitled "Art Furniture," made a polemical call for architects to try to engage more with furniture design. They made this call particularly in relation to the demise of the architect-led Art Furniture Company.

Despite this plea, in the following year, the same journal acknowledged the current way of house furnishing: “The best and most truly economical plan for anyone about to decorate and furnish is to go to some respectable house combining both branches, give an idea of what he likes (having an estimate if he wishes) and wash his hands of the whole till it be finished” (“Interior Decoration — The Drawing Room,” p. 122). Even so, there were distinctions within the choices available. The article went on to say: “It will generally be found advisable, when anything beyond simple painting and papering is intended to employ men whose prime business is that of decoration rather than upholsterers who have added decoration to their original occupation, for it requires a much higher art-education to produce a good decorator than a good upholsterer....” The differences were important to this journal, and they clearly indicated the role of education as a characteristic of a profession. This training was not only in terms of actual interior works but was also related to the understanding of the client and their needs, wants and aspirations. The same article noted that a decorator

must be guided in a great measure by the money at his disposal and by the position of his customer. It stands to reason that objects which would be thoroughly in keeping in the apartments of a banker or leading physician may appear, in the residence of a pawnbroker or a retired butcher, simply snobbish, though they may be perfectly able to afford them; but it requires no little tact to give effect to such considerations without giving offence. [143]

This need for an understanding of the niceties of social structures was as important as the more practical knowledge of design, materials and processes.

A satinwood display cabinet made by Holland & Sons, 1868.

A very revealing comment about the application of education in the furnishing trade is found in the following passage. In 1863, the Committee of Council on Education took evidence from the furniture company Holland’s about the value of art education to the decorating trade. In answer to the question as to “the practical value of the art instruction given in the schools,” the firm stated:

We find those workmen who have studied at the School of Art so considerably in advance, that we have much less trouble with them in directing, having acquired a knowledge of style, which is essential in our business. We would much rather employ workmen who have received instruction there, it being a recommendation. We insist upon all our apprentices attending during their apprenticeship. It is most valuable to us and all engaged in architectural and ornamental decoration. ["Tenth Report," p. 191; Collinson & Lock took the same view.]

The importance of education in the design and production of interior work was not lost on other contemporaries. In 1869, Building News discussed the decorations of the contractor and politician Sir Morton Peto’s Kensington home and chastised the upholsterers Jackson and Graham for the quality of their interior decoration work. Even though the firm employed distinguished designers, the architectural press still played out the arguments about the loss of control of work from the architect to the "upholsterer." They wrote scathingly that:

The decorations were unfortunately taken out of the architects hands and given, together with the furnishing, to Messrs. Jackson and Graham, a firm of upholsterers whose reputation for the quality and artistic excellence of their goods stands deservedly high, but whose notions of decoration appear to consist in the indiscriminate application of Mr. Owen Jones’ objectionable crudities. In the case we refer to the delicate Italian modelling of the plaster ceiling appeared cheek by jowl with coarse quasi-Moorish flat ornaments, and the whole rejoiced in the tender colouring which graces St. James's Hall and the buffet at the Charing Cross Station? [121]

Following this demolition of Owen Jones's designs, they then wrote: “Had a firm essentially decorative, such as Messrs. Crace, for instance, been employed, the beauties of the internal architecture would have been brought out by the decorative treatment, while the furniture would probably have been quite as good as that actually supplied" (121). They made the distinction between the upholsterer and the decorator very clear.

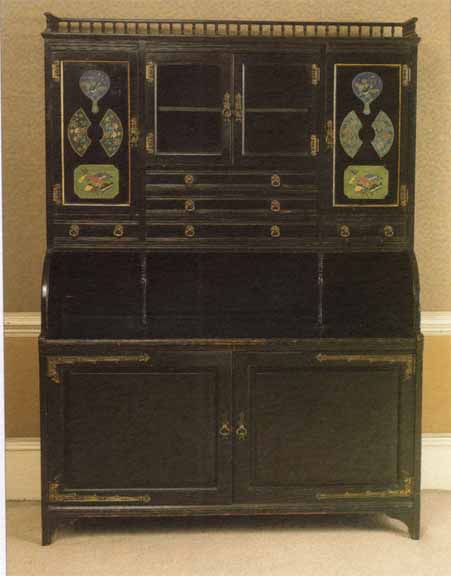

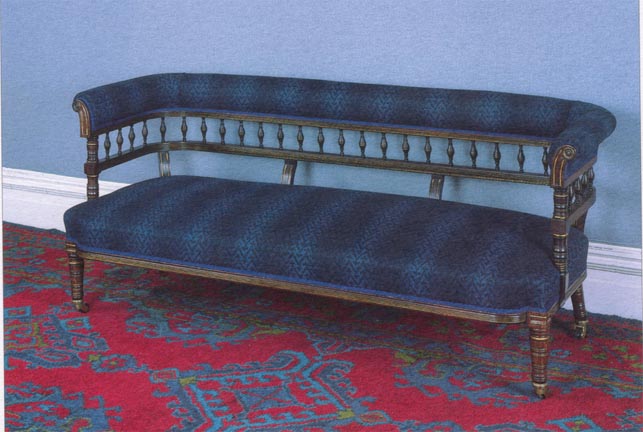

Left: Aesthetic Movement cabinet by Collinson and Lock, c. 1888. Right: Sofa by the same company, c. 1875.

The understanding of this distinction, and their ability to work closely with architects and professional designers, brought about the tremendous success of new businesses such as Collinson & Lock, as well as the refocused older-established businesses. Therefore, although these businesses comprised both cabinetmakers and upholsterers, as well as decorators, the epithet of art furnisher raised them to a higher plane.

The attacks on upholsterers continued sporadically and resurfaced in a campaign published in The Builder in 1878. This time, the journal railed against the furniture trade generally and its construction techniques in particular. It seems that this was another thinly disguised attack on the appropriation of the traditional role of the architect. Stefan Muthesius suggests that “The Builder’s invectives [against the furniture trade] must be seen as an attempt to strengthen, [or indeed regain] the architectural profession’ foothold as overlords in all matters of interior and furniture design” (115).

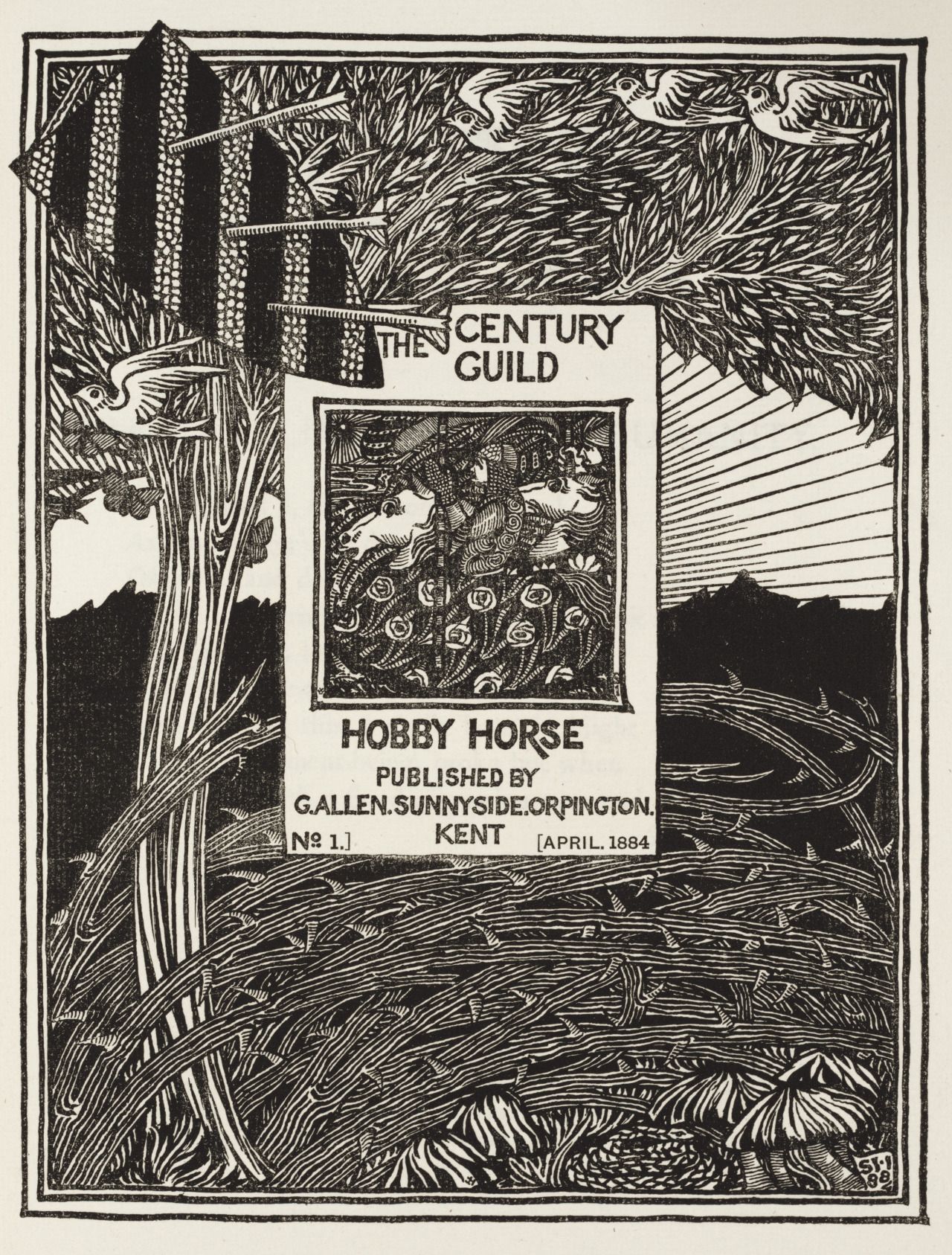

The first edition of the Hobby Horse.

The arguments rumbled on as Arthur H. Mackmurdo appeared to offer a sensible solution in the first edition of the Century Guild’s journal Hobby Horse in 1884.

By means of the co-operation of artists associated through the Century Guild, it is possible to maintain some sort of alliance between the arts when conjointly employed; thus putting stop to the battle of styles now raging between architecture and her handmaidens — a battle that mars by crude contrast of unrelated character the beauty and repose of our homes. [Back matter]

Even by the near end of the century, the author and dealer Frederick Litchfield, writing in 1892, returned to the issue of the role of the architect and the consequences of a loss of control over furniture design.

About the early part of the nineteenth century, the custom of employing architects to design the interior fittings and the furniture of their buildings, so as to harmonize, appears to have been abandoned... furniture therefore became independent and beginning to account for herself as Art, transgressed her limits... and grew to the conceit that it could stand by itself... [244-45]

Conceit or not, the best of art furniture was to have important ramifications in terms of influence on design. Juliet Kinchin has pointed out the significance of Collinson & Lock in achieving success where others had failed: “The importance of Collinson and Lock lay in providing a framework for the realisation of such reformers' [e.g., Eastlake, Godwin, Talbert and Webb's] ideas and spreading them to a wide public through their commercial success and efficiency” (47).

Link to related material

Note

Subsequent chapters in Professor Edwards's book:

- Insights into the workings and productions of a Victorian London furnishing business

- Information on a wide variety of topics including furniture design developments, interior design styles, business practices, working practices and techniques, and the firm’s customers and competitors

- The structure of the London "art furniture" trade and its development

- The firm’s business growth, its involvement with important international exhibitions, the designers they worked with, and the furniture and interiors produced

- Involvement of the firm with both public and private interior decoration commissions examined via case studies, including those in the Anglo-Japanese, Queen Anne, Old English, and Renaissance styles used in the later Victorian period

Bibliography

“The Architect versus the Cabinet Maker and Others”, The Fine Arts Journal 13 (February 1847).

“The Architectural Exhibition.” The Builder. 4 April 1863.

Back matter. The Century Guild. Hobby Horse. No. I (April 1884). Sunnyside, Orpington, Kent: G. Allen.

Eastlake, C.L. Preface. Hints on Household Taste. 2nd ed. London: Longmans, Green, 1869.

“Interior Decoration — The Drawing Room.” Building News. 5 and 12 February 1869.

Kinchin, Juliet. “Collinson and Lock.” Connoisseur. May 1979.

Litchfield, Frederick. Illustrated History of Furniture: From the Earliest to the Present Time. London: Truslove and Shirley, 1892.

Muthesius, Stefan. “We do not understand what is meant by a ‘Company Designing’: Design versus Commerce in Late Nineteenth-Century English Furnishing.” Journal of Design History. 5. 2 (1992).

Tenth Report of the Science and Art Department of the Committee of Council on Education. London, House of Commons, 1863.

White, Allison C. “What's in a Name? Interior Design and/or Interior Architecture: The Discussion Continues." Journal of Interior Design VXVII, 35, No. 1, 2009.

Wyatt, Matthew D. Reports on the Paris Universal Exhibition, Part I. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode 1856.

Created 7 July 2022