HAT is called the aesthetic craze in dress is a sort of reaction from the stiffened, over-weighted, and tightened fashion perpetuated by the tyranny of the modiste, whose chief idea is to put as much material as possible into a feminine garment without regard to convenience or health. The suggestions conveyed by such costumes as were seen on the stage in Mr. W. S. Gilbert's "Patience" are certainly not without their value; and the taste for subdued and harmonious colours has become so general, that a glaring red, an emerald green, or a cerulean blue, is never seen now in what is commonly known as polite society.

Dress must of necessity be regarded from two points of view, and I think it can be shown that the one is almost identical with the other. I mean that the first thing to consider is what gives and secures health to our bodies; the second, what gives pleasure to the eye of ourselves and others, by reason of its beauty. It needs no education in the mysteries of physiology to discover that to check and impede, by whatever means, the free and perfect action of the muscles, must lead of necessity to their degeneration and ultimate destruction; nor does it require any abstruse mathematical problem to demonstrate that the hidden organs of the body, supposed by nature to have a certain amount of space to exist and work in, can do neither if that space be gradually restricted; and that as the body itself grows larger, and the organs of breathing, digestion, and circulation have more onerous duties imposed upon them, they require to be free from external pressure and constriction to carry on a healthy existence. It would almost seem as if common sense alone might teach people that interference with the natural and perfect form of the human bod}' — whether by the bandaging of any limb or the displacement of any organ — must produce disastrous consequences; and it is surprising to find that the constant reiteration of this truism, with instances and illustrations, should be necessary still.

Left: The Greek Style. Right: The Divided Skirt. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

I am disposed to believe that the existing indifference to the sacrifice of health entailed by modern dress is due to the false idea of beauty which has taken possession of those who lead the fashions in civilised communities. A recent writer on "Beauty" tells us that the mischievous person who first presented the grotesque outline of the body seen when the waist has been artificially "improved" was a certain Norman lady who lived about three hundred years ago; but Charles Kingsley says that, in the letters of Synesius, Bishop of Cyrene — a place on the Greek shores of Africa — written about twelve hundred years since, mention is made of a slave girl from the far East, who was shipwrecked on the coast, and was regarded as a curiosity by the Greek ladies who rescued her, by reason of her pinched wasplike waist. She was sent from house to house and beheld with astonishment and laughter; for "with such a waist" it seemed impossible to these ladies that a human being should breathe or live: "so they petted the poor girl and fed her as they might a dwarf or a giantess, till she got quite fat and comfortable, while her owners had not enough to eat."

Any society or institution that deals with matters affecting the health must take note of the many serious evils that result from the modern follies of compression and distortion in feminine attire; and so the National Health Society, which professes to "diffuse the knowledge in the laws of health in every possible way, amongst all classes of society," feels it incumbent on itself to commission a competent surgeon and anatomist to denounce, with all authority and solemnity, the practices of those Englishwomen who offend against natural laws, and to endeavour to bring on a better state of things by volunteering some practical suggestions as to hygienic clothing.

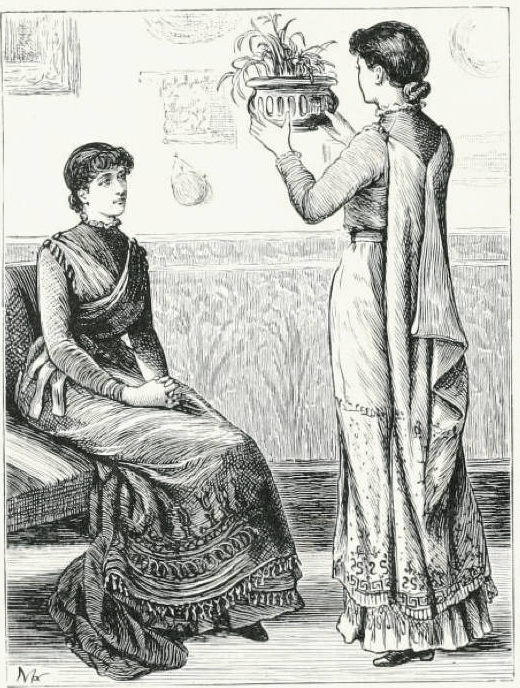

Left: Artistic Dresses. Right: Child's Costume. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

For those who have submitted for years to the tyranny of fashion, and have deformed both their figures and their feet, there is not much to be done. The muscles which are weakened will scarcely now recover their strength, and the bones which have been twisted, in the feet and body alike, must remain as they are. It is with young girls not yet subjected to the process of deformation that the effort at improvement should be made; if they can be delivered from the Moloch of fashion, we may hope much for another generation. The lectures given at Kensington and elsewhere under the auspices of the Society created great interest. This was extended by an exhibition of hygienic garments. With only a few days' notice, a collection was made of such things as, I suppose, were never before exhibited; they were on view no more than five days; but during that time thousands of women saw that consideration of the subject bail already borne fruit, and that there was room for improvement and suggestion still. To this end another exhibition of the kind will be held next year, when all who have contributions to make are invited to make them, and when new lights maj possibly be thrown on the difficult question, "how best to combine health, freedom of movement, and the artistic requirements of beauty with the exigencies of modern life." It must be confessed that up to this time no perfect solution of the difficulty has appeared. Many creditable attempts have been made, and each suggestive costume has something to recommend it in one direction or another. The overflowing attendance at the recent exhibition, where there was comparatively little to see, proves that the female mind is deeply exercised by the question;, and very ready for practical hints about reform.

A society of ladies calling itself the Rational Dress Society exhibited a dress which is said to be advantageous for walking or active exercise of any kind. Its chief feature is the divided skirt, which, its advocates say, does away with the inconveniences attached to heavy drapery and to dresses which prevent the leg from moving freely. Moreover, by its means each limb is separately clothed, and warmth and decency alike are secured. In order not to offend popular prejudice, the skirt — as may be seen from our second illustration — is so arranged and dissembled by the kilting round its edge as to be scarcely distinguishable from an ordinary dress. The lady who was the first in society to wear this form of skirt speaks highly of it, and adds that, hygienically, its value is doubled by the fact that it does not rest on the waist for support, but is fastened by buttons on to a waistcoat fitted to the shoulders. To get rid of the conventional appearance of a waist ridiculously small, she wears a Zouave jacket with a full Garibaldi sort of front, in some pretty soft material, which makes a kind of pendent pouch over a loosely fastened waistband. Several admirable tennis and boating dresses made in this fashion were shown, and I can quite imagine that modifications of it will become popular for out-door exercise.

When matters of costume and personal adornment are discussed, those with artistic tendencies have naturally much to say; and the familiar acquaintance which all students of art must have with the most beautiful conceptions of an art-loving nation, such as Greece was in her day, undoubtedly exercises an influence on their taste and judgment. They do right to associate the finest specimens of art with ideas of health, grace, and power almost unknown in these degenerate days. To walk through the corridors of the British Museum is to feel inclined to say, " Such men and women can be, for they have been; and they may be yet again, if we will but make real use of science instead of only boasting about it."' A somewhat modernised Greek dress — figured in our first picture — had its place in the exhibition. It was lent by Mrs. Pfeiffer, who, attired in one, most simple and well suited to the occasion, herself took frequent opportunity to explain its merits and its adaptability to modern life.

All dress reformers insist on the minimum amount of underclothing being worn, so as to diminish weight. To secure warmth, the use is advocated of the garment known as a "Combination," made of warm flannel or other material, according to climate. Over this is worn a boneless or very light form of corset, specimens of which were on view; and to this again is buttoned an upper skirt, made usually in the divided form. Mrs. Pfeiffer wears a perfectly plain princess dress, made much like a teagown — of silk, velvet, cashmere, and so forth — above which there is arranged the typical drapery — the shawl, or chiton — which must of necessity be of soft and yielding material. The under-dress may be worn high or low according to circumstances; and when full dress is required the sleeves may be dispensed with, for the drapery when properly arranged hangs gracefully over the arm. This drapery is composed of a piece of material — soft silk, china crepe, or gauze — the size of which is regulated by the stature of the wearer, the rule being that the width shall be double the square of the person, measured from finger-tip to finger-tip with the arms extended, the length being taken from the point of the shoulder to within two inches of the ground. "When this diapering is doubled it forms an oblong square. Two buttons sewn on each shoulder of the under-dress secure four loops fixed to the four upper corners of the drapery; and the centre of the shawl, hanging in a fold like a burnous between the shoulders to below the waist, forms the back of the garment. The arrangement of the folds across the chest and over the sides of the dress is perfectly simple, and is easily learnt. The garment may be worn with or without a girdle round the waist, and in cither case is essentially classical and graceful. In addition to its perfectly natural and beautiful form, its other advantages are many and great. It is as easily folded and packed away as an ordinary shawl, and the under-dress can be worn at any time without its ornamental drapery. Its advocates permit no trimming nor embroidery upon the shawl but such as is absolutely wrought into it, and no fringe that is not part of the material. It possesses every element of permanency, and allows of no sham nor cheap imitativeness in ornamentation. Whether it be worn with a short under-skirt for walking and with folds drawn through the girdle so as not to be in the way, or as a graceful evening dress with flowing skirts of rich material and beautifully embroidered drapery, it appears to me to commend itself to lovers of art and sanitary reformers alike, and must impart a sense of naturalness and dignified repose to every one who wears it. Mrs. Pfeiffer lent the exhibition one lovely white India muslin chiton, or diploidon, elaborately embroidered with Indian gold, to be worn over a white satin under-dress; with one of dark myrtle-green satin, with drapery of soft silk of the same colour. The absence of frills and trimmings and the quiet intrinsic beauty of these dresses were remarkable.

By many who make their gowns according to their own idea of beauty, and not according to the regulation fashion of a French or English milliner, an artistic Old English costume will perhaps be preferred to one imitated from the antique. There were dresses — made in rich satin; one of a soft grey colour, another of deep myrtle-green — with plain skirts having but a small frill at the edge, and full bodices with bands high up round the waists, which offered no temptation to compression, as the skirts were set full into the waist and fell in graceful folds to the feet. The full bodices were gathered down round the shoulders and in again at the waist. The sleeves were large and full, and in the grey one they were cut into two talis in front, allowing soft white muslin to appear as an under-sleeve, furnished at the wrist with a ruffle of good old laee to match a soft hanging collarette round the neck. The tabs, or fastenings to the front part of the sleeve, were held together over the muslin by two jewelled buttons of curious workmanship. Altogether these dresses — a good idea of which may be got from the specimens figured in our third picture — were very pretty and suggestive. They might be made in less costly but soft material, and would permit the application of the very beautiful elastic needlework known as "smocking," instead of the little gathers commonly used. For children's costumes the elastic ornamentation of this kind for neck and wrists is very suitable and very pretty. Many of various colours were exhibited which allowed free play to the muscles, and were trim and dainty in appearance. One of these is shown in our fourth illustration. Smocking is work that but few can do well; and like all ornament worked into the substance of a garment, it gives a superior and permanent appearance to everything to which it is applied.

The promoters of the exhibition had round the room drawings of perfect female figures from well known statues, with a cast of the Venus of Milo, so remarkable for her beautiful but powerful form. Feet such as artists love to paint, feet that had never known the deforming influence of a shoe, were contrasted in drawings and models with feet the result of years of compression and torture; and reasonable coverings for the foot, strong and comfortable and not unsightly, were sent in for exhibition from many makers. Hygienic stockings — stockings fingered like gloves — were also on view. Pedestrians tell us that such separation of the surface of the toes is very advantageous and comfortable when the feet are completely shod. With sandals only, which are but soles to tread on, the division would not be n -nary. As the exhibition included only feminine garments, and only ladies were admitted to see, there were exhibited all known devices for improving their present wear. Oculists have often made great and justifiable objections to the use of spotted or figured net in veils. Advantage was taken of this fact to exhibit veils of wire ground net with an invention attached which should altogether supersede the unhand unbecoming respirator. It consists of a piece of thin delicate wire gauze introduced into a deep hem at the bottom of the veil. Fastened over the face in the usual way, it comes just before the nose and mouth, and, whilst acting as a respirator, is quite unnoticeable in appearance.

Whatever may be thought of the form which recent criticisms on dress have taken, and of the evident, dissatisfaction with the present state of things that exists in some circles, it is certain that the attiring of the body, and its suitable and pleasant adornment, may be classed amongst "the lesser arts of life/' and as such deserve the attention of all reasonable men and women. The teaching of such men as Ruskin and William Morris is that the "lesser arts of life" are those which satisfy our bodily wants, and that they should be studied to make common things beautiful, and our daily life a pleasure and a joy. That their teaching is of great and permanent value is a fact that cannot be too vigorously presented. It enables us to make beauty and health and comfort the common material of life; and we shall do well to extend it, not only to the homes we inhabit, but to the clothes we wear. Perhaps at no period of history has there been greater freedom in the makes of dress; and therefore there is less excuse for the adoption or perpetuation of any monstrosity which may he said to be fashionable. Never were women better able to appear attired after their own devices, and according to their own ideas of reasonableness, deeency, and propriety, without exciting remark or derision. With this freedom to encourage, and the teachings of artists, philosophers, and physiologists to guide us, surely there will one day be evolved a manner of dress for women which will be at once sensible and graceful. Surely we may hope for a costume constructed with due regard to the fitness of things, and to the avocations of the wearer, which shall cheek the restlessness of Fashion and imply a recognition that all which appertains to us, whether in personal attire or domestic surroundings, should be expressive of our individuality, and not of slavish obedience to a code of fashion which disregards the requirements of health and common sense, and imposes on us not only ill-health but ugliness.

Bibliography

“Fitness and Fashion.” Magazine of Art. 5 (1882): 336-38. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 23 October 2014.

Last modified 23 October 2014