Unless otherwise specified, the photographs used here are by the present author and come from our own website. They can be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, or, when they appear in longer documents, for more information.]

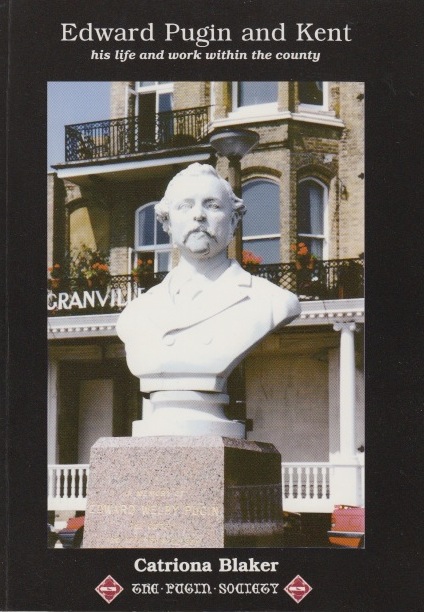

Cover of the book under review

A. W. N. Pugin died at home in Ramsgate, Kent, in 1852. His illness had been traumatic not only for himself but for his whole family, and his premature death at the age of 40 placed a huge burden of responsibility on young shoulders. Still only eighteen, his eldest son Edward Welby Pugin was left to complete his father's outstanding commissions, and support his step-mother Jane and his six younger siblings. He rose to the challenge admirably. Not only did he keep the family afloat, but he expanded its concerns to include offices in London and Liverpool as well as Ramsgate. With the passage of time, he produced a large number of new buildings of all descriptions, designed their fixtures and fittings in a distinctive style, and acquired a national, even an international reputation. Focussing on his work in Kent, Catriona Blaker both traces and celebrates his emergence from the shadow of his more famous father.

Chapter One ("Prelude") deals with Edward's family background, particularly his life at The Grange, Ramsgate, where he had been largely educated by his father, especially in the professional skills that he needed now. It was here, where his father had built both The Grange itself and his own church, St Augustine's, that Edward was particularly active. We learn in Chapter Two ("Ramsgate") that apart from making notable additions to both house and church, and building St Augustine's Monastery opposite the church (1860-61), he designed an attractive house for a family friend, Alfred Luck (completed in 1862); the Isle of Thanet Steam Flour Mills (1865, with later additions by other hands); and terraced housing on Artillery Road on the East Cliff (also around the mid-60s). There are various other rows of houses, such as one on Codrington Road on the West Cliff, that are almost certainly his as well.

Examples of Edward Pugin's work in Ramsgate. Left to right: (a) The splendid Digby Chantry in St Augustine's Church. (b) The covered walkway that draws the visitor into The Grange. (c) Detail of the eye-catching brickwork on the terrace attributed to him on Codrington Road.

Perhaps most entertaining here are the glimpses we get of the man himself, his charm, bearing and larger-than-life presence. Behind the naming of Artillery Road in 1866, for instance, lies the story of the dashing "Captain Pugin" of the Cinque Ports Artillery Volunteers. Much as his father fancied himself a sailor, Edward cast himself in the role of a military man, taking particular pride in his skill at target shooting, and particular delight in his Corps members' winning the Queen's Prize in competition in 1866: "not only was Pugin at this point the Glorious Captain of the Volunteers but he even, in his artistic role, designed a series of cups for winners in the national contests" (13). Later, Blaker paints a memorable picture of him "galloping furiously along the East Cliff at Ramsgate with his four fearsome dogs" (61). In sheer vitality, too, he seems to have been a chip off the old block!

Edward remained a staunch Catholic like his father, and was much in demand from Catholic clients. Yet, of the local churches discussed in Chapter Three ("Churches in Kent"), the most intriguing is probably the Anglican St Catherine's, in Kingsdown near Sittingbourne (1864-65). Blaker describes it as "exotically startling and ornate" (28) — not the first time the word "ornate" has been used of his work. In general, Edward had been pulling away from his father stylistically, the contrast clearly seen in such showy embellishments to his father's buildings as the oriel window of St Augustine's Presbytery, and also in the High Victorianism of the Digby Chantry in St Augustine's itself. Rather than tamely following in his father's footsteps, he was, says Blaker, "an original.... highly industrious, able, and at times capable of daring and imaginative work" (2). In some of his more elaborate designs, she suggests, he might fairly be seen as a Gothic "rogue" architect (6), an interesting and surely valid point of view.

The Granville Hotel in 1870, complete with tower, though minus the clock faces that Edward had once envisaged. Source: from a private collection, with many thanks.

Chapter Four ("The Granville Hotel") takes us to the high point of Edward's architectural career in Kent — and, sadly, the turning-point of his fortunes. He clearly liked to build in the grand style, but there was more scope for this in the midlands and the north, with their rich patrons and larger Catholic congregations. Now here was an opportunity for it on his own doorstep. In Ramsgate as in other coastal towns, the arrival of the railways had led to a boom in the tourist trade. For Londoners, Ramsgate was one of the more easily accessible resorts, and William Powell Frith's painting of 1854, Ramsgate Sands, vividly depicts its popularity even before the London, Chatham & Dover Railway reached it in 1863. Now cliff-top development gathered pace, and Edward embarked on a project to build some luxury private residences on the East Cliff. What finally materialised, says Blaker, was "one of his most sensational and individual buildings" (37), and one of the era's grandest seaside hotels. Here he turned from "a more predictable, if contemporary use of northern Gothic, to a functional muscular massing of huge areas of masonry" (40) — with the kind of eye-catching detailing that he liked, and that drew attention to the structural frame and fenestration. Best of all, it was to have a tower of enormous proportions, seemingly intended to draw comparisons with the one that his father had designed for the Palace of Westminster. In this case, however, it was not only to make a statement and provide a landmark, but to house the water for the guests' wide variety of speciality baths (saline, ozone, Turkish etc.)! In fact, as Blaker points out, this was a perfectly rational response to the changing demands, as evidenced by other grand seaside hotels of the time (see for example the Hydro Hotel, Llandudno, of 1860).

The Granville opened with great fanfare, and achieved national fame, attracting visitors like Wilkie Collins and the architect Richard Norman Shaw. However, as a speculative venture, it proved disastrous, and Chapter Five is ominously entitled "The Fall." Details of Edward's dismissal from the Artillery Volunteer Corps in 1869, his filing for bankruptcy in 1872, and complicated court cases like the one against the contractor for the Granville in 1874, do indeed make sorry reading. No one could be fairer or more sympathetic towards him than Blaker, who understands so well the pressures on him, and the way they affected the "over-excitable and irascible nature" that he undoubtedly inherited from his father (2). But she is not alone in making such allowances for him: he was his father's son in his generosity too, and her appreciation of this matches the support he won in his own lifetime from the working men of Ramsgate, many of whom he had employed, or helped in other ways. Early in what was to be his last year, they presented him with a silver salver, with a heartfelt inscription declaring their gratitude towards, and sympathy for, one who had "rendered signal service" to the town, and had displayed "manly and straightforward conduct ... more particularly in recent events" (53). This kind of support, in the teeth of failure, is not easily won.

Edward continued to drive himself on. There is a tantalising reference at the end to his visit to America, where he won a number of new commissions. But his efforts to recover from ruin were blighted by ill health and his life ended almost as prematurely and tragically as his father's, at the age of 41. Blaker notes that shops were closed in Ramsgate at the time of his funeral, and the harbour flags were flown at half-mast.

A. W. N. Pugin was an architect with a vision so compelling that it changed the face of the country — at least as regards its built environment. It was a hard act for his eldest son to follow, but, as Blaker shows, Edward made a surprisingly good hand at establishing his own reputation and style. Examining the view that his best work was his earliest, when he was closest in spirit to his father, she agrees that he "assumed with respect and loyalty the mantle of his father," but says in her final brief chapter that he had worn it "with a difference. In particular, his secular, commercial work proclaimed him both to be an original designer, and also to be in tune with the demands of his age" (58-59). Direct comparisons are difficult here: it is hard to imagine the elder Pugin ever designing a luxury hotel. But Edward built his share of churches too, and Blaker has made it clear that he proved himself flexible and innovatory when it came to these as well.

This attractively produced and illustrated book is very involving, and a pleasure to read. Well laid out with descriptive chapter headings, it has copious endnotes and a bibliography to encourage further study of the younger Pugin's output in other parts of the country and abroad. Blaker has done her subject proud, bringing out the ways in which he did indeed emerge from his father's shadow — and, most importantly, enabling us to appreciate the results much more fully than we might have done before.

Related Material

- Ramsgate, West Cliff (a painting dated 1857)

- Ramsgate Sands, No. 1 (Punch (1867)

- Ramsgate Sands, No. 2 (Punch (1867)

- Great Expectations in "The Tuggses at Ramsgate," or, The Importance of Being Cymon

- The Seaside in the Victorian Literary Imagination

- The Granville Hotel under renovation (2010)

Book under Review

Blaker. Catriona. Edward Pugin and Kent: His Life and Work within the County. The Pugin Society, 2012. 71pp. £5.00. ISBN 0-9538573-1-X. See Pugin Society Publications.

Last modified 7 July 2014