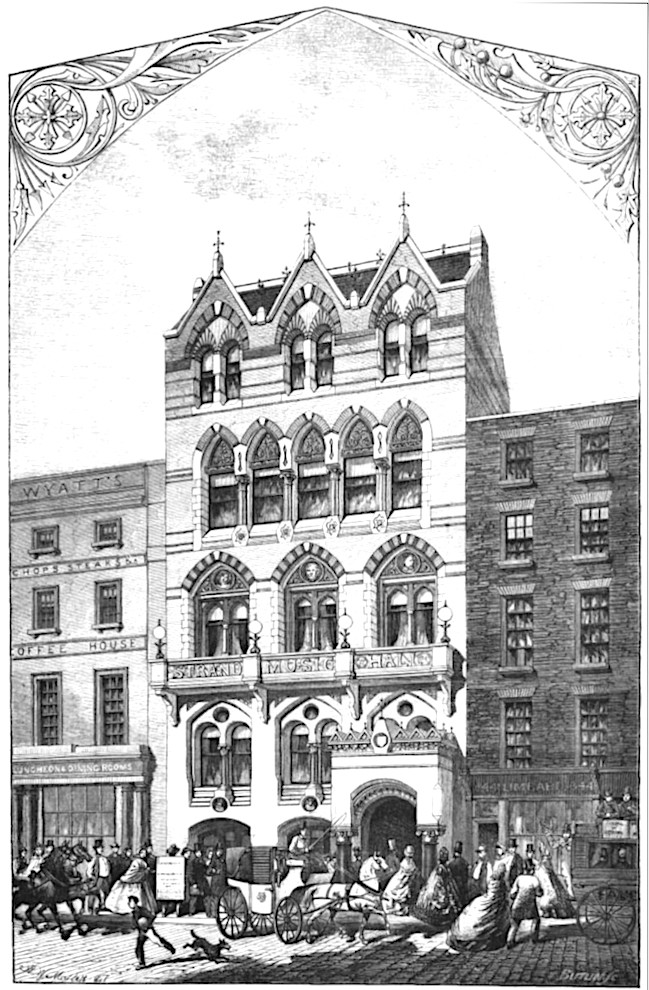

The Music Hall's Strand frontage. Source: "The Strand Music Hall," The Building News (20 November 1863), facing p. 868.

The Strand Music Hall, designed by Bassett Keeling when he was still only 26, opened on 17 October 1864. Keeling might have foreseen the ecclesiastical establishment's criticism of his unconventionally designed churches. But the abuse heaped on his venture into theatre architecture was perhaps less predictable. After all, here was a kaleidoscope of elements which, as the Building News critic noted on 20 November 1863, when it was near completion, could have been "painted on canvas with happy effect, as the 'palace scene' in an extravaganza." Apt enough as a setting for music hall productions, surely? The trouble was that to this commentator, as to other contemporary architectural critics, such an assemblage "implies a solecism in Art when solidified in brick, stone, &c." ("The Strand Music Hall," 868). Thus the Building News of 16 June 1865, almost eight months after it actually opened, merely noted tersely in passing, "The Strand Music-hall, by Mr. Keeling, is now finished, but its exaggerated style is to be regretted" ("The Ecclesiology of the Last Year," 434).

Keeling's design daringly incorporated features that were unusually placed or proportioned, and the earlier critic specifies them, with mounting outrage:

You never know where you may not expect to find an arch or an arcade; and when you do find them, they are low where you would have supposed they must have been lofty, and solid where as certainly they ought to have been light. And the spandrels are at least as perplexing and contradictory as the arches; when very small, large heads protrude from them, which provoke inquiry as to how they could possibly have got there. In like manner the capitals appear actuated by a common desire not to belong to the shafts which are supposed to carry them. Then, in every direction there are the strangest chamfers, which reveal unexpected half-hidden slender shafts, which grow out of nothing, and go nowhere, and having nothing to do, do it; and with these chamfers must be associated the innumerable notches, facets, and other queer cuttings, which are doubtless intended to take their part in the universal ornamenting, while in reality they fail altogether to be ornamental. Colour also has been treated precisely after the same fashion as all these varied forms of chisel-work. Variously-coloured bricks have been brought into strong contrast with one another, and with white stone; and paint has had its capabilities put to the test without reserve or hesitation. ["The Strand Music Hall," 868]

With this kind of criticism, the Music Hall became a "succès de scandale in architectural terms," as Edmund Harris puts it (The Rogue Goths (120). And who knows, some well-received shows might have helped the architecturally intriguing theatre to become a must-see attraction on this important thoroughfare. But Keeling was most unfortunate in a matter over which he had no control. The productions themselves, which had been expected to "enable the classical amateur to revel in the emanations of the loftiest genius" and provide "music of a superior class" (The Era), failed to satisfy the authorities: "Mr. Pownall, Chairman of the Middlesex Magistrates, in his evidence before the committee appointed by the Government to inquire into the present theatrical licensing system, says — 'The end of amusement should be to elevate the lower classes, and not to bring the higher class of amusements down to the level of the lower classes' ("Strand Music Hall," Illustrated Sporting News, 225). Therefore (according to the same source) they acted with an "uncalled-for and unwarrantable stretch of authority" and refused to grant the new theatre a licence in 1866. The whole very costly enterprise failed, and a sad little note appeared in The Builder of 3 August 1867, under the heading "Miscellanea": "The sale of this freehold property, consisting of the Strand Music Hall (now closed), together with the adjoining houses and shops in the Strand and Catherine-street, has been attempted by auction at the Mart in Tokenhouse-yard, City, by Messrs. Chinnock, Galsworthy, & Chinnock. The site is described as extending over an area of 14,000 ft. The auctioneer started the bidding at £40,000. No advance being offered on that sum, it was withdrawn from sale. A portion of the site was next offered, but, as no bid was made over £30,000, no sale was effected" (459). So at first it was hard to get rid of the building, indeed the whole site, for a reasonable sum — although it did change hands soon enough.

All this was a great shame because even the earlier Building News critic had at least been impressed by the "general arrangements" of the building: "The various rooms required in an establishment of this kind are well planned, and they all work well. The communications also and the staircases are good, their sole failures arising out of their participation in the architectural character of the edifice." As for the auditorium itself, this was not only "worthy of commendation for its arrangements," but had "one very important feature" — a magnificent ceiling "formed of tinted glass, divided into panels by beams and pendants of cut crystal glass" with lighting "effected by means of gas jets above this ceiling, which shine down through it with beautiful effect" ("The Strand Music Hall," The Building News, 868).

The same Building News critic had particularly complemented the glass-making firm, Messrs. Defries and Sons, on the "very clever and completely successful transparent and luminous ceiling" here, saying that it "produced artificial sunshine in a manner that is so pleasantly suggestive of the shining of the great luminary itself" ("The Strand Music Hall," The Building News, 868).

Moreover, when another appraisal appeared in the same periodical later, after the theatre had opened, it carried a hint of praise. Yes, G. Huskisson Guillaume accepts, it was was indeed an "unmeaning design" with a "distracting multiplicity of splays, notches and stops," so that "any connection or definite expression, save that of comicality, is utterly lost." Still, he allows, "the architect has given us in it a pretty complete repertory of modern art - dexterity and eccentricities - valuable as showing our consummate finesse in detail, or, as it has been aptly called, 'acrobatic' Gothic" (267). It is hard not to see Huskisson's expression, "consummate finesse," as at least some kind of complement.

Perspectives were shifting now, with the appearance of High Victorian works by acknowledged masters like William Burges. But it was too late for Keeling. Neither the auditorium, "sheer phantasmagoria" in itself (Harris, "Technicolour Gothic"), nor the useful practical arrangements, could save what might have been seen as his pièce de resistance, and this extraordinary slice of architectural and theatrical history was lost. Even its frontage, at first only partly changed when it was replaced by the much more successful Gaiety Theatre in 1868, would be completely demolished in 1903 to make way for the new layout of the Aldwych. Keeling did not live to see this last and final blow to his ambitious project, nor to see a small item in Builder that year, under the heading, "The Old Gaiety Theatre and its Site," to the effect that the "novel and original" style he adopted for the Music Hall, although criticised at the time, "has not been without its influence since" (266-67).

Bibliography

Curl, James Stevens. "Going Rogue: An interesting if unappealingly illustrated reassessment of a neglected style." The Critic. Web. 31 March 2025. https://thecritic.co.uk/going-rogue/

"The Ecclesiology of the Last Year." The Building News Vol. 12 (16 June 1865): 433-34. HathiTrust, from a copy in the libraries of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Web. 1 April 2025.

The Era, 16 October 1864. In "The Gaiety Theatre, Aldwych, Strand, London Formerly - The Strand Musick Hall." Arthur Lloyd.co.uk. Web. 3 April 2025. http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/GaietyTheatreLondon.htm#strand

Harris, Edmund. The Rogue Goths: R.L. Roumieu, Joseph Peacock and Bassett Keeling. Swindon: Liverpool University Press for Historic England, 2024.

_____. "Technicolour Roguery: the rise and fall of Bassett Keeling." lesseminenetvictorians.com. Web. 3 April 2025. https://lesseminentvictorians.com/2020/11/01/technicolour-roguery-the-rise-and-fall-of-bassett-keeling/

Guillaume, G. Huskisson. "Connection and Contrast Considered as Important Elements in Progressive Art." The Building News and Engineering Journal. Vol. 13 (5 October 1866): 657-58. HathiTrust, from a copy in the libraries of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Web. 1 April 2025.

"Miscellanea: The Strand Music Hall." The Builder. Vol. 25 (3 August 1867): 579. Internet Archive. Web. 2 April 2025.

"The New Strand Music Hall." The Art-Journal. New series Vol. 4 (1865). Internet Archive. Web. 2 April 2025.

"The Old Gaiety Theatre and Its Site." The Builder. Vol. 85 (12 September 1903): 266-67. Internet Archive. Web. 2 April 2025.

"Sectional View of the Interior of the Strand Music Hall, London." Building Illustrations: Private Houses, Public Buildings, and Warehouses (no further details given). Internet Archive, from a copy in the Getty Research Institute. Web. 2 April 2025.

"The Strand Music Hall." The Building News and Engineering Journal. Vol. 25 (20 November 1863): 868. Google Books. Free ebook.

"The Strand Music Hall." Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review Vol. 5 (21 April 1866): 225. Internet Archive. Web. 2 April 2025.

Created 3 April 2025

,br/>Last modified 29 May 2025