Photographs by the author, who would like to thank both Canon Andrew Shanks and Cathedral Office Assistant Grace Timperley for their help in identifying and explaining the nineteenth-century additions. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one. [Click on the images for larger pictures.]

The southern side of Manchester Cathedral, showing late 19c. and early 20c. additions by Basil Champneys.

Although the history of this Grade I listed building goes back to medieval times, a great deal of work took place on the fabric after it became a cathedral in 1847. In particular, the exterior was repaired and refaced in the 1850s-70s, under the diocesan architect J(oseph) S(tretch) Crowther (1820-1893), during which period J. P. Holden rebuilt the west tower (1862-68; see Hartwell 47). Later, Crowther added a north porch and Basil Champneys (1842-1935) added west and south porches, and an extension to the south.

Porches

Left: South Porch (1891). Right: Artist's vision of the west or Victoria porch, given in an article in the Manchester Times of 14 January 1898, asking for subscriptions ("Manchester Cathedral"). Note that the crocketed turret is shown on the south side; it would be built on the north side.

Rev. Thomas Perkins, rector of Tunworth, Dorset, and prolific cathedral commentator for Bell's publishers, published his description of the Cathedral in 1901. By this time, he could already list the south porch among the not "obviously new" additions (5). It was similar to the one on the north side rebuilt to designs by Crowther about two years earlier. The one on the south, he explains, "was erected by James Jardine in 1891" (10), James Jardine having been a Manchester cotton magnate and benefactor (see Wyke 23-24). So the south porch does not seem to have occasioned any comment. But the more elaborate west porch was another matter. It was built by public subscription to mark Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee, to provide "a covered approach to the Cathedral, to be used on state occasions by ecclesiastical and civil dignitaries," and also to "lend importance to the western extremity of the Cathedral" and compensate for the "barrenness of the tower on its western side" ("Manchester Cathedral"). It certainly turned out to be grand. But the Rev. Perkins was dubious on several counts. He felt that it detracted from the height of the tower, and he criticised its assymetry — specifically, its "single crocketed turret." He also found a certain lack of freedom in the elaborate carving — a "freedom that is so great a charm in old work." He did however admit that Champneys had "succeeded in training carvers to carry out his designs in an admirable manner." It should be remembered that this was written when the porch was brand new, and indeed "still showing the colour of the stone fresh from the carver's hands" (13-14). It has of course weathered now, and blends in well.

Extension

Part of the southern extension, 1090-03, connecting to the Cathedral offices on the east side of the building and leading out to the elevation seen in the main picture above, with the central bay window. The memorial in the foreground is to a former Dean of Manchester, Joseph Gough McCormick, who held that office between 1920-1924.

The Rev. Perkins had yet to see this part of the Cathedral built: "At the present time, 1901," he writes, "further building operations are being carried on in the yard on the south side of the church." (12). Clare Hartwell describes Champneys' work here as "excellent, as one would expect, subdued in contrast to his porches, yet charmingly varied in the grouping and with felicitous decorative passages such as the bay windows to the S." (49). The bay with the windows that she mentions is reminiscent of the corner turrets at Champneys' John Rylands Library. The extension now houses the Bishop Wickham Library and the song school, offices, and other facilities.

Reredos

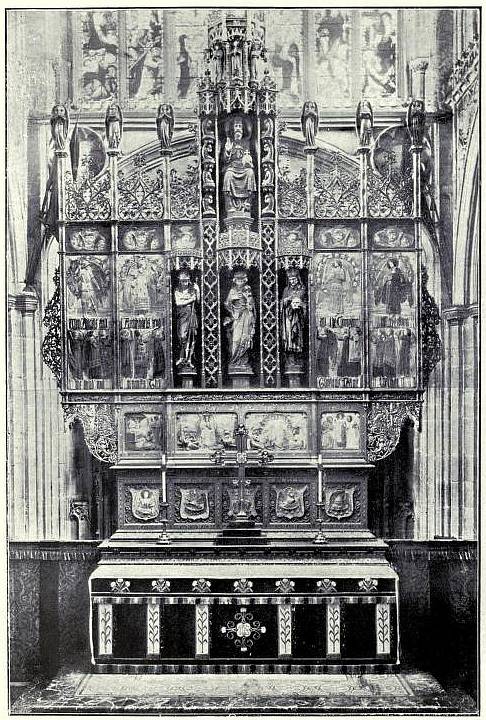

High Altar and Reredos by Champneys, with the low relief panels and figures in the round modelled by George Frampton, as shown in "Review," p. 48.

Champneys also had some important work in the Cathedral interior, on which he collaborated with the sculptor George Frampton (see "Afternoons..," 206). The Rev. Perkins does not attribute the reredos to him, but simply writes:

Behind the altar is an elaborately carved wooden reredos of modern work, richly painted and gilt. The upper part ... is wider than the lower; it is divided vertically into seven divisions, the two lateral divisions on each side being themselves divided into two tiers. The three central niches contain figures of the three patron saints, St. George on the north, the Blessed Virgin in the centre, and St. Denys on the south side. Above the central figure, St. Mary, is another niche containing a seated figure of Christ, holding in His left hand an orb and cross, His right hand raised in the act of blessing; above this figure is a canopy. On the top of the six uprights that form the vertical divisions of the reredos, angels stand with clasped hands. The carving on the smaller panels illustrates the following verses of the "Preface to the Sanctus" which are inscribed beneath them. "With angels and archangels and all the company of heaven / We laud and magnify Thy glorious name. Amen." (46)

Frampton himself told an interviewer from the Studio journal how he "modelled the low-relief panels and the figures in the round" ("Afternoons," 206). Unfortunately, the reredos was damaged in World War II. But, even without the blitz of 23 December 1940, it might not have lasted. A few weeks after the devastating air raid, a local physician participated in a visit to the cathedral by the Lancashire and Cheshire Anitiquarian Society, to see the bomb damage. He recorded in his diary that the canon who acted as their guide "was especially pleased that the marble pulpit and reredos are damaged, for he was already plotting to get rid of them" (qtd in Powell 9). They were probably deemed over-elaborate, perhaps too "heavy," at that time. However, the reaction today might have been different.

Related Material

Sources

"Afternoons in Studios: A Chat with Mr. George Frampton, A. R. A." The Studio, Vol. 6: 205-212. Google Books (available for preview). 12 November 2012.

Hartwell, Clare. Manchester. Pevsner Architectural Guides. London: Penguin, 2001. Print.

Parkinson-Bailey, John. Manchester: An Architectural History. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. Print.

Perkins, T. The Cathedral Church of Manchester; A Short History and Description of the Church and the Collegiate Buildings now known as Chetham's School. London: George Bell, 1901.Internet Archive. Web. 12 November 2012.

Powell, Michael. "The Blitz." Manchester Cathedral News. Dec.-Jan. 2010/11: 7 -9, 12. Web. 12 November 2012.

"Review of the Architectural Work of Basil Champneys, B. A." Academy Architecture, Vol. 45 (1914): 33-52. Internet Archive. Web. 12 November 2012.

Wyke, Terry, with Harry Cocks. Sculpture of Greater Manchester. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2004. Print.

Last modified 12 November 2012