As the editors of The Illustrated London News explain in a later issue, both sketches by Army and Navy officers and drawings by the newspaper’s artists took weeks longer to reach London than did text, such as this article’s, which arrived quickly via telegraph. The illustrations I have include appeared in the issues of 21 and 28 February. — George P. Landow

The Fall of Karthoum. The Illustrated London News placed this bulletin at the top cetner of the page in large, extra-spaced type. Click on images to enlarge them.

The Commander-in-Chief's despatches to the War Office published in our Journal last week gave an account of the battle tought at Abou klea, twenty-three miles from Metammeh, on Saturday, the 11th ult., by General Sir Herbert Stewart, with fifteen hundred men of his advanced brigade, against nearly ten thousand of the Mahdi's army and of the battle on Monday, the 19th, between the Wells of Shebacat and Metammeh, within sight of the Nile; when a second attack of the enemy was repulsed, enabling the British force to gain a secure position at Gubat, on the bank of the river two miles above Metammel; and to meet the armed steam-boats which General Gordon had sent down from Kuurtoum, conveying tour hundred black troops of the Khartoum garrison.

The latest news from Gubat communicated last week by Lord Wolseley, to the date of Saturday, the 24th, stated that Sir Charles Warren had gone up to Khartoum by steamer, with a small guard of the Sussex Regiment; while, Sir Herbert Stewart having been wounded on the 19th, the command of the troops at Gubat was taken by Colonel the Hon. E. T. Boscawen, of the Coldstream Guards. The lists of officers killed and wounded in the two actions were also given, with the names of two newspaper correspondents, Mr. J. A. Cameron, of the Standard, and Mr. St. Leger Herbert, of the Morning Post, who were killed in the second conflict on the 19th.

The correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, Mr. Burleigh, was slightly wounded, having a graze on the neck and his foot struck by a spent bullet. He was able, nevertheless, to send that journal an animated description of the fighting on the 19th ; this was published in the Daily Telegraph on Friday of last week. The Daily News had already, on Thursday, the 23rd, published the letter of its correspondent, Mr. H. S. Pearse, giving an account of the first battle on the 17th, this letter being written on the very day of the battle. We now reproduce, with some abridgments, these narratives by eye witnesses of both engagements; which may be compared with those supplied by the official despatches.

The Battle of Abou Klea, Jan. 17

Mr. Pearse writes as follows:—“Yesterday morning we had bivouacked and breakfasted at the south-east side of the great plain, with distant hills to the right and left, and a black and rugged ridge in front, over the saddle of which the caravan route leads to Abou Klea. The 19th Hussars had gone on to reconnoitre, and we heard the sound of distant rifle-shots. About noon came news from Major Barrow that the enemy were holding the Wells.

Camel Corps Forming Square to Receive Enemy’s Attack. “Sketch by our special artist, Mr. Melton Price.” Source: The Illustrated London News 86 (7 February 1885):

“General Stewart immediately made his dispositions for attack, massing the brigade in line of columns, the Guards on the right, the Heavy Camel Corps in the centre, the Artillery and Engineers in the rear of the Guards forming the right face of the square. Lord Charles Berestord's Naval Brigade was similarly posted behind the Mounted Infantry. The Sussex Regiment, on foot, closed up the rear, and all the baggage was in the centre. In this compact square of column, the brigade moved forward as steadily as if on parade, and halted four hundred yards from the foot of the ridge, while General Stewart and his staff went forward across it to recon noitre.

“Thinking it too late then to advance and attack without knowing the actual strength of our foes, General Stewart wisely resolved to form a zereba for the night, with flanking squares strongly occupied, and pickets holding posts on the loity hills on our left. All night long we were harassed by shots from the heights a thousand yards distant. On the opposite flank there was the continuous hissing of bullets overhead. Now and then one fell in the square, but only two men and a camel were hit. Our sleep was not very sound. Thrice the men were called to arms before dawn, when a general attack on our position was expected. This morning all was quiet until after breakfast. Then the fire recommenced from the stone breastworks constructed during the night on the heights on our right and rear. This was only a feint fire, and was soon suppressed by the Mounted Infantry.

“By eight o'clock, the enemy developed considerable strength on the right front, coming over the black stony hills in good order in two long lines, with banners flying bravely. At the same time some force of the rebels began creeping stealthily up the grassy Wady on our left front, the direct road to the Wells. The screw-guns battery made good practice. Two or three shots checked the advance for some time. Our position in the bellow, with lines extended along the ridge, was strong and well covered. Nevertheless, several men were hit. One of the Heavy Camel Corps was killed early in the action. Another of the Mounted lufantry was dangerously wounded within a few yards of where I write. A camel close by was hit by the next shot. The rebels evidently made skilful use of their Remingtons. But our Martinis' fire, hitherto restrained, was now beginning to tell effectively. At half-past nine the enemy's scouts were reported trying to creep round the hills on the left flank. Barrow's Hussars were sent forward to check this. Meanwhile, the fire in the centre of the line was hotter every minute.

“At ten o'clock, General Stewart determined upon a counter-attack, and tormed a hollow square, the Guards in front, the Mounted Infantry on the lett dank, the Sussex Regiment on the right, the heavy cavalry and Naval Brigade, with a Gardner, in the rear, the camels, with the ammunition and hospital stretchers, in the centre. We advanced two miles exposed to a heavy fire on all sides. We moved out to the attack under a hail of bullets. Men dropped from the ranks right and left, but none of the wounded were left on the tield. The medical staff, under Surgeon-Major Ferguson, worked splendidly under the heaviest fire. There were frequent stoppages for these purpose, which made progress slow. It was nearly an hour belore we sighted the enemy's main body, and realised that at least 7000 or 800 men were against us. We halted and closed square; General Stewart took up a good position on the slope where the rebels must advance uphill, across open ground. Skirmishers of the Mounted Infantry were sent forward to force on the attack, while Captain Norton's battery of screw guns planted several shells among the densest mass. The concealed enemy sprang up, twenty banners waving, and came on in a splendid line. The troops on the right were led by Abu Saleh, Emir of Metammeh. On the left they were under Mahomned Khair, Emir of Berber. The latter was wounded, and retired early; but Saleh came desperately on at the head of a hundred fanatics, escaping the withering fire of the Martinis marvellously, until shot down in the square. The rear face, composed of the heavy cavalry, broke forward in the endeavour to fire on the rebels, who swept round the flank and broke into us. Then came the shock of the Arabs' impulsive charge against our square.

For a moment, there was much confusion, and the fate of tho whole force trembled in the balance, until the steadiness of the Guards, Marines, and Mounted Infantry prevailed. The Sussex Regiment, though taken in rear, rallied and fought desperately. The men ſell back, re-formed in good order, and poured volleys into the enemy, every one in the leading division falling dead in our midst. In the temporary confusion, the Gardner gun could not be got into action at the most effective moment. When it opened fire, the rebels were close on it. The Naval Brigade therefore lost very heavily; Pigott and De Lisle were both killed. But the greatest losses fell on the Heavy Camel Corps, or whose officers six were killed and two wounded. The Guards moved not an inch, even when the rear was threatened simultaneously with the front. Among the first of our officers mortally woundedwas Colonel Isuruaby, who tell gallantly in lfight close to his old comrades the Blues.

“When we had time to look, we saw that line after line of the enemy had tallen under the Mutini fire as they advanced. There could scarcely have been less than eight hundred or a thousand of dead and wounded Arabs. Others in scattered bands made off in various directions, leaving the ground strewn with dead and wounded, with arms and banners. Major Barrow's Hussars came up soon after, but were too late to strike at the retreating foes, many of whom, however, were shot down while retiring. The enemy had fought with the most reckless and admirable courage, and displayed great tactical skill. They harassed the zereba all the previous might, and endeavoured to lead us into a skilfully-laid trap.

“I escaped unhurt amidst the hand-to-hand mêlée with the loss of my horse. After the fight, in which the enemy brought all their best troops against General Stewart's bligade, we gained the Wells of Abou Klea, and bivouacked there last night.”

The Advance from Abou Klea

The following is the better part of Mr. Burleigh's letter:— “A fierce battle and hard-won victory had secured to us the Abou Klea Wells, giving the troops an abundant supply of water, with something for the horses and camels. By night fall, we were collected inside a rather weak, irregular, and incomplete zereba. The front face, instead of being formed of cut brushwood, was protected by low walls of rough stones. An undulation in the ground left an opening in the wall twenty-five yards wide. The wall itself was twenty inches high, and the zereba was nearly 200 yards square. Each man had his pint of water served out - half a day's supply — and on that quantity he had to work, march, and fight in a thirst provoking country. Lights were all ordered out at dusk, and the troops lay down in square formation, with their alms beside them ready for instant use.

“By dint of hard work and going without sleep, the column was ready to resuule its forward march on Sunday at four p.m. The old zereba was empted, all the supplies having been transported to the Wells by working overnight; and a new small zereba and fort were built at Abou Klea, a detachment of the Sussex Regiment and a few men of the Royal Engineers being left to hold that post. “It was given out by General Stewart that the force should only go five miles out and encamp till morning. The column got off punctually, tired though the men and animals were. Nearly one hundred camels were taken with the column to carry water, ammunition, and cacolets. These were all inside the square. It was with pleasure that we set our faces to another forced march so that we might get to the river. Instead of making a protracted halt at sunset, the column rested a few minutes only, to allow the darkness to settle down. Then, altering our course so as to avoid Shebacat Wells and the Arabs posted there to intercept or hinder us, we struck due south into the Desert, attempting to reach the Nile before daylight, and before the Arabs could stop us. The General sought to avoid another battle until the force should have intrenched itself, or, at any rate, packed its baggage by the water's edge.

“Part of the way, the force moved in columns of regiments, the Mounted Infantry leading, with the Hussars in advance and on the flanks. Although this increased the width of our front, it did not diminish the length of the column. Ali Gobah, the outlaw robber chief, directed our course, which was at times rather circuitous—now south, then south by west, and again south by east. Sir Charles Wilson and Captain Verner of the Rifles looked after Ali, in whose experience as a path finder they both trusted.

“Daylight broke, finding the column six miles from the river, and about the same distance south of Metammeh. The objective point was to occupy a position on the Nile four miles south of Metammeh. An hour before sun rise we had altered our course, turning more to the east. Before the sun was up, we saw that the enemy was on the alert all along our front. Streams of men on horseback and on foot came from Metammeh, interposing themselves between the column and the water we longed to gain. For a short time, Sir Herbert Stewart deliberated whether to push on two miles nearer the Nile. As the Arabs mustered in sufficient force seriously to threaten our advance, he decided to halt upon a ridge of desert covered with sparkling pebbles, four miles from the river. To our right and rear lay a few low black hills, one mile to two miles distant; on our front, the Desert rolled downward towards the green flats bordering the Nile; for here, as at Dongola, the belt of cultivation is rich and wide.”

The Battle of the Nile, Jan. 19

“Turning with a light smile to his staff, General Stewart said, ‘Tell the officers and men we will have breakfast first, and then go out and fight.’ The column was closed up, with the baggage animals to the centre, as usual; the boxes and pack-saddles being taken off, to make an inclosure to protect the square from rifle fire. In less than ten minutes the Arabs were not only all over our front and flanks, but had drawn a line around our rear. Groups bearing the fantastic Koran inscribed banners of the False Prophet, similar to those of which we had taken two or three score at Abou Klea, could be seen occupying vantage-points all around. The enemy's fire grew hotter and more deadly every minute. Evidently their Remingtons were in the hands of Kordofan hunters. Mimosa bushes were cut, and breakfast preparations were suspended for an hour, whilst most of the troops lay flat. Fatigue parties strengthened our position. In going towards a low mound, a hundred yards on our right front, where we had a few skirmishers, General Stewart was shot in the groin. The command devolved upon Lord Charles Beresford by seniority, but he, being a naval officer, declined it, and Sir Charles Wilson took it over. One of the most touching incidents in the zereba was the wounded General tended by his friends, two or three of whom wept like men, silently. Poor St. Leger Herbert, the Morning Post correspondent, one of these, was himself shot dead shortly afterwards.

“The mound on our front was quickly turned into a

detached work, forty volunteers, carrying boxes and pack

saddles, rushing out, and, in a short space of time, converting

it into a strongly defensible post. Gradually, the enemy's

riflemen crept nearer, and our skirmishers were sent out to

engage them. They were too numerous to drive away; and the nature of the ground, and the high trajectory of their Remingtons, enabled the Arabs to drop their bullets, into the square at all points. Soldiers lying behind camels and saddle packs were shot in the head by dropping bullets. Mr. Cameron; the standard correspondent, was hit in the back and killed whilst sitting behind a camel, just as he was going to have lunch. The enemy were firing at ranges of from 700 to 2000 yards, and their practice was excellent. The zipping, and thud of the leaden hail was continuous; and, while the camels were

killed in numbers, our soldiers did not escape, over forty

having to be carried to the hospital, sheltered as well as

possible in the centre of the square behind a wall of saddles,

bags, and boxes. As a precaution against stampede, the poor

camels were tied down, their knees and necks securely bound

by ropes to prevent their getting upon their legs. The enemy's

fire increased in intensity; and, as stretcher after stretcher

with its gory load was taken to the hospital, the space was

found too little, and the wounded had to be laid outside.

Surgeon-Major Ferguson, Dr, Briggs, and their colleagues

had their skill and time taxed to the utmost. Want of water

hampered their operations; doctors and patients were alike

exposed to the enemy's fire.

“Our situation had become unbearable. We were being

fired at without a chance of returning blows with or without

interest. The ten thousand warriors whom the Mahdi had

sent from Omdurman to annihilate us were blocking our road

to the Nile; and over a hundred Baggara, the horsemen of the

Soudan, and crowds of villagers, who had joined Mohamed

Ahmed's crusade, hung like famished wolves on our rear and

flanks, awaiting an opportunity to slay. Apparently, they were

emboldeued by our defensive preparations.

“There were three courses open to us—to sally forth and fight our way to the Nile; to fight for the river, advancing stage by stage, with the help of zerebas and temporary works; or to strengthen our position, and try to withstand the Arabs and endure the lack of water, till Lord Wolseley should send a force to our assistance; we, meanwhile, sending a messenger or two back to Korti with the news. It was bravely decided to go out and engage the enemy at close quarters. At two p.m. the force was to march out in square, carrying nothing except ammunition and stretchers. Each man was to take a hundred rounds and to have his water-bottle full. Every thing was put into thorough readiness for this enterprise. Lord Charles Beresford, with Major Barrow, remained in command of the inclosure, or zereba, containing the animals and stores. They had under them the Naval Contingent, the 19th Hussars, a party of Royal Engineers, and Captain Norton's detachment of Royal Artillery, with three screw-guns, and details from regiments and men of the Commissariat and Transport Corps.

Facsimile of a Sketch by the Late Lieutenant De Lisle, R.N.

“It was nearly three o'clock before the square started, Sir Charles Wilson in command, and Colonel Boscawen acting as Executive Officer. Lord Airlie, who had been slightly wounded at Abou Klea, and again on the 19th, together with Major Wardroper, served upon Sir Charles's staff, as they had done upon General Stewart's. The square was formed to the east of our inclosed defence, the troops lying down as they were assigned their stations. The Guards formed the front, with the Marines on the right front corner, the Heavies on the right and right rear, the Sussex in the rear, and the Mounted Infantry on the left rear and left flank. Colonel Talbot led the Heavies; Major Barrow, the Hussars; Colonel Rowley, the Guards ; Major Poé, the Marines; and Major Sunder land, the Sussex Regiment. Captain Werner, of the Rifle Brigade, was told off to direct the square in its march towards the river. When the order was given for the square to rise and advance, it moved off to the west to clear the outlying work.

“The instant the Arabs detected the forward movement on our part, they opened a terrific rifle-fire upon the square from the scrub on all sides. In the first few minutes many of our men were hit and fell. The wounded were with difficulty picked up and carried. When the square slowly marched, as if upon parade, down into the grass and scrub-covered hollow, intervening between the works we had constructed and the line of bare rising desert that bounded our view towards the south and east—shutting out of sight the river and the fertile border slopes—all felt the critical movement had come.

“Steadily the square descended into the valley. Gaps were made in our force by the enemy's fire. As man after man starvered and fell, these gaps were doggedly closed; and, without quickening the pace by one beat, onward our soldiers went. All were resolved to sell their lives dearly. Every now and again the square would halt, and the men would lie down, firing at their foes hidden in the valley. Those sheltered behind the desert crest were too safely screened to waste ammunition upon at that stage. Wheeling to the right and swinging to the left our men fought like gladiators, without unnecessarily wasting strength or dealing a blow too many. A more glorious spectacle was never seem than this little band in broad daylight, on an open plain, seeking hand-to-hand conflict with the courageous, savage, and fanatical foe, who out numbered us by twelve to one.

“As the square moved over the rolling ground, keeping its best fighting side—or rather its firing side—towards the great on-rushes of the Arabs, the soldiers swung around, as though the square pivoted on its centre. Once it entered ground too thickly covered by grass and scrub, halted, and coolly swung round and marched out upon the more open ground, with the Arabs to the right front, their “tom-toms' beating, and their sacred battle-flags of red, white, and green flying in the air.

“Bearing banners lettered with verses from the Koran, a host of fanatic Arabs was the first to hurl its swordsmen and spearsmen upon the square. The column wheeled to receive them, and the men, by their officers' direction, fired volleys by companies, scarcely any independent firing being permitted. The wild dervishes and fanatics who led the charge went down in scores before our fire, which was opened on them at 700 yards, and none of the enemy got within some yards of the square. This checked their ardour, which had been excited by seeing the gaps in our ranks. Three more charges were attempted by the enemy at other points along the line of the square's advance.

“At half-past four, after nearly two hours' incessant fighting, as the column neared the south-easterly edge of the valley to pass out of it, the Arabs made their final grand rush. Nearly 10,000 of them swept down from three sides towards the square, their main body—numbering not fewer than 5000– coming upon our left face. It was a critical moment. Their fire had made fresh gaps in our ranks, and fierce human waves were rolling in upon every side to overwhelm our force. Down the Arabs came from behind the ridge at a trot, and not at the top of their speed, as the Hadendowas charge. Gallant horsemen and wild dervishes led them, and shouted to their followers to rush on in Allah's name and destroy us. Firm as a, rock, the square stood steadily, aimed deliberately, and fired. Again and again had volleys to be sent into the yelling hordes as down they poured. The feeling was — Could they be stopped before closing with us? Their fleetest and luckiest, however, did not get within twenty five yards before death overtook them; while the bulk of the enemy were still a hundred yards away. At last—God be thanked! — they hesitate, stop, turn, and run back. Victory is ours, and the British column is safe! The broken lines of Arabs sullenly retreated towards Metammeh; but our square had to gain the ridge before escaping from their sharp shooters' fire, or getting a chance of punishing the daring foe. Without further, opposition, the British advanced to the river, and encamped in a sheltered ravine for the night; the men lying down with their arms, and strong outposts being on the alert against any surprise. Every man drank freely of the refreshing water, and, exhausted by the hardships endured, slept soundly, grateful that the enemy left them undisturbed for that night.”

Position of the Advanced Force

Gubat, On the left bank of the Nile two miles above Metammeh, and ninety-eight miles below Khartoum, is the site of the fortified camp occupied since Jan. 19, by the troops under command of Colonel Boscawen. General Sir Herbert Stewart, with other wounded officers, is in a steam-boat on the river. General Sir Redvers Buller, V.C., when he arrives with the Royal Irish Regiment, will take command of the advanced force; he started from Korti on Thursday week.

Sir Charles Wilson’s Reconnaissance of Khartoum: Conflict with the Enemy opposite Omdurma. “Sketch by our special artist, Mr. Melton Price.” Source: The Illustrated London News (21 February 1885).

Colonel Sir Charles Wilson, R.E., with twenty men of the Sussex Regiment, went, up to Khartoum by one of the steam-boats on Saturday, the 24th, and it is probable that he has arranged future movements with General Gordon. His return to the camp has been eagerly expected. The safety of the camp at Gubat is not doubtful, or the sufficiency of its Provision supplies. Its stores of ammunition are superabundant, and there is not the slightest risk of their being annoyed by the two or three thousand Arabs who are watching them, Quite close by, behind the mid walls of Metammeh village.

Since the desperate battle of the 19th, the Arabs have once marched out from the fortified village to wards Stewart's intrenchments, but when they saw the English come out to meet them, they prudently retired. Provisions must have been sent to Metammeh from Gakdul; a quantity of stores was brought down by Gordon's steamers; and the Nile banks about the intrenchment, with the island in rear of the English lines, contain large supplies of grain and cattle. The advanced brigade may therefore be fairly described as tolerably well off. No sickness has broken out in camp, and the wounded are making satisfactory progress to recovery. The village of Gubat consists of 130 houses, and has 700 inhabitants. It is surrounded by vegetable gardens, which supply the population of Shendy. Here is also a burying ground containing some graves sacred to the Mohammedan world, those of saints who lived and preached at Shendy, as well as local chieftains and dervishes. The place is visited by all caravan travellers. Under Ismail Pasha a good road was commenced from Metammeh towards Khartoum, but it was completed only as far as El Hadjir; but on the other bank there is an excellent road all the way to Khartoum.

Cheering the Arrival of Four of Gordon’s Steamers at Metammeh, during the First Attempt on the Town, Jan. 11th. “Facsimile of Sketch by Our Own Special Artist, Mr. Melton Prior.” Source: The Illustrated London News (28 February 1885).

The appearance of General Gordon's steamers was dirty and much battered, though protected by wooden screens. They were, however, full of goats and grain supplies. The crews have their families on board, and all manifested great delight on the arrival of the British troops, by letting off rockets throughout the night and by singing and dancing. The steamers have each a kind of crow's-nest high up on the mast, which is used by the look-out man.

The Royal Irish Regiment started from Korti on foot on Wednesday week, with their baggage and water supplies carried on camels. The next regiment to follow will be the West Kent. On the Desert sands a rate of twenty miles a day would not be considered too great. It could be done if there were urgent need of reinforcements at Gubat; but as the Gubat brigade appears to be anything but harassed by the enemy, a marching rate of fifteen miles is supposed to be sufficient for Sir Redvers Buller's column. The distance from Korti to Gubat is 180 miles.

General Earle’s Movement toward Abou Ahmed

Our readers will not have forgotten that a separate advance has been undertaken by General Earle, with a large portion of Lord Wolseley's army, going in boats up the Nile from Korti, north-east to Abou Ahmed, in order to secure the Nubian Desert route from Korosko, and to proceed afterwards in a southerly direction to Berber. It was expected that they would have to fight the hostile Monassir tribe at Birti, above the Fourth Cataract, but this week's news, forwarded by Lord Wolseley from Korti, seems to make it likely that no resistance will be made to the advance so far as Abou Ahmed. On Sunday morning General Earle, with Colonel Butler, a squadron of the 19th Hussars, the Egyptian Camel Corps, and half a battalion of the Black Watch, reconnoitred the enemy's position at Birti. Finding that all was quiet, they pushed on and entered the village, and discovered that the enemy had evacuated the place, leaving behind only some women, old men, and their stores of grain, and cattle. They seem to have been alarmed by the numerous flotilla of boats, and the occupation of both banks of the riverby our advancing troops. Several influential sheikhs of the Monassir tribe, and two uncles of Suleiman Wad Gamr, the chieftain who murdered Colonel J. D. Stewart and Mr. Frank Power, have given themselves up. It is stated that the Arabs have retreated direct to Berber. Upon this point all the prisoners speak positively, and say that some of the Berber troops were with Suleiman. Their retirement to Berber will enable the communications to be opened up between Korosko and Abou Hained, and will permit of stores being sent on to us there across the Desert.

Our Illustrations

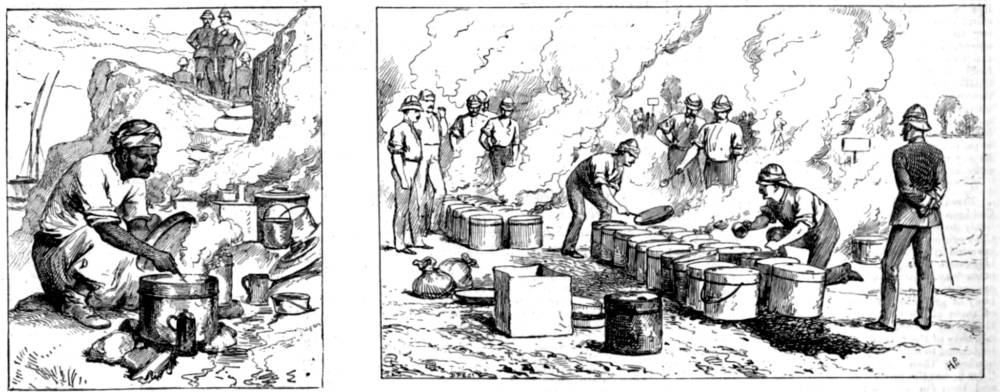

Mr. Melton Prior, the Special Artist of the Illustrated London News, is with the advanced force at the intrenched camp of Gubat, unless he has already gone up to Khartoum; he accompanied Sir Herbert Stewart's march across the Desert, and was present at the battle of Abou Klea on Jan. 17, and at the battle on the 19th, where his friend and comrade, Mr. Cameron, Special Correspondent of the Standard, was killed. We shall no doubt receive from Mr. Prior, as soon as possible, abundance of Sketches of these incidents of the campaign; but our readers will bear in mind that Sketches cannot be sent home so quickly as the verbal narratives of newspaper correspondents, which are telegraphed from Korti to London. The Illustrations presented this week are therefore of a date some few days before the final advance of Sir Herbert Stewart's complete force; and the scene at Gakdul Wells is that of the arrival of the first column of troops. The Guards' division of the Camel Corps is shown on the march in the Desert; and Major Kitchener, with his Guides, preparing to lead the way, and to discover the unknown route. Some of the scenes in the head-quarters' camp at Korti, represented by our Special Artist's Sketches, are highly characteristic of this singular military Expedition. The drilling of the Camel Corps, and especially training those strange beasts to endure the alarm of a cavalry charge passing close to the formed square, was a very curious sight for British soldiers. Lord Wolseley's frequent inspections of each part of the force at Korti; the fatigue party of the Highlanders (42nd Black Watch) who have since followed General Earle up the Nile; the Christmas entertainments heartily enjoyed by all the men, including an amateur concert, at which a sailor gave a song; the lighting of a grand bonfire, and the boiling of the Christmas pudding; the bivouac of the Special Correspondents, not in tents, but with the scanty shelter of a few blankets suspended between the trees—these and other features of campaigning life in the Soudan are cleverly delineated by our Special Artist.

Left: Concert at Korti — a Sailor ‘at Sea’ in the Desert of the Soudan. Middle: Christmas Eve at Korti: Bpiling the Christmas Pudding for the “Heavies.”. Right: What a Time the Pudding Takes to Boil!.

The cataracts of the Nile, so far as his present experiences are concerned, seem to be left entirely behind; he is no longer among the boats in their toilsome struggle with the rapid current and the labyrinth of rocks; but we have added two of his Sketches of the river banks, those of the old Fort at Debbeh, and of Hannek, the reputed birth-place of the Mahdi, which is not far above Korti in going up to Merawi.

Christmas Eve at Korti: Clearing the Ground for the Bonfire

Related Material

Bibliography

Illustrated London News 86 (31 January 1885): 112-113. Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of a copy in the University of Chicago Library. Web. 21 August 2020.

Last modified 24 August 2020