Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

Introduction

The Churchman’s Family Magazine was set up and edited by the publisher John Hogg (the brother of James, the proprietor of London Society), and appeared for a decade, 1863–73. Issued monthly in a limp orange-yellow wrapper displaying an ecclesiastical design by John Leighton (King, pp. 140–41) and sold at a shilling, it was one of several periodicals intended to challenge the dominance of The Cornhill Magazine, Once a Week and Good Words. Generally aimed at parallel middle-class audiences to those addressed by its rivals, The Churchman’s Family Magazine offered the usual blend of fiction, poetry and short articles, with the added attraction (again in the manner of its fellow journals) of high-quality wood-engravings in black and white.

Its variety, as another periodical containing ‘miscellanea’, is heavily promoted in a publicity sheet issued by Hogg at the end of 1865. According to this advertisement, the journal contains ‘Tales, Domestic Sketches [and] Poetry’ as well as ‘Biography, History, Travel [and] Science’ while also containing ‘Stories for the Young’ and general articles on ‘Garden Recreations’ and ‘Natural History’.

This is the same territory as Once a Week and the others, although Hogg’s periodical’s pitch is more narrowly focused around two claims. It is supposed to be ‘Essentially a Family Magazine’ (which meant it did not contain literature that was unsuitable for children); and it directs some of its effort (as suggested by its title) towards the reporting of issues connected with the Anglican Church and its worshippers.

In practice, though, the claim to be a ‘church magazine’ is over-stated. As the publicity sheet makes clear, there are articles on ‘Church questions of the day’ and ‘Social questions from the Church point of view’. Yet Hogg’s editorial practice is far from tightly focused. He wanted to appeal to the clergy and the devout, but in the final assessment the emphasis is more on ‘Family’ than on ecclesiastical issues, faith, or the workings of Anglicanism. In the words of contemporary reviews reprinted on Hogg’s publicity sheet, the magazine has something for all ‘intelligent readers’ (Brighton Examiner), and is invariably ‘healthy, cheerful, thoughtful, instructive [and] never dull’ (Liverpool Observer).

The magazine was nevertheless relatively short-lived. The audience for this sort of miscellaneous material was strongly contested, and Hogg’s attempts to challenge his competitors’ journals was ultimately unsuccessful. The periodical closed in 1873 following a couple of years of sharp decline. Most of its rivals continued until the end of the century.

The Churchman’s Family Magazine: Illustrations

The magazine contains illustrations by some of the outstanding designers who contributed to the visual idiom known as ‘The Sixties’. Hogg enlisted contributions by Millais, Poynter, Lawless, Morten and Sandys, as well as work by more traditional artists, notably Selous (Gleeson White, pp. 63–5). In the absence of surviving documentation little is known of the publisher’s dealings with either his artists or his engravers. However, the visual outspokenness of some of the designs suggests that Hogg (as editor) exerted only limited influence over the illustrators’ choice and treatment of their subjects. In practice, there are several occasions where the visual texts are anything but closely matched with their letterpress, a tendency that can be found in many illustrated journals of the period, but in this magazine is allowed to run out of control (Cooke, pp. 71–83).

The disjunctures found in The Churchman’s pages are exemplified by the ambiguous relationships between the words and illustrations in volume two, which covers the second half (July–December) of 1863. This is characteristically a matter of visual expansion in which the image extends or modifies the messages contained in the writing. The illustrations consistently modify the texts’ emphasis on faith and redemption, re-focusing the reader/viewer’s attention on intense representations of human frailty and suffering in which there is little sense of the presence of God.

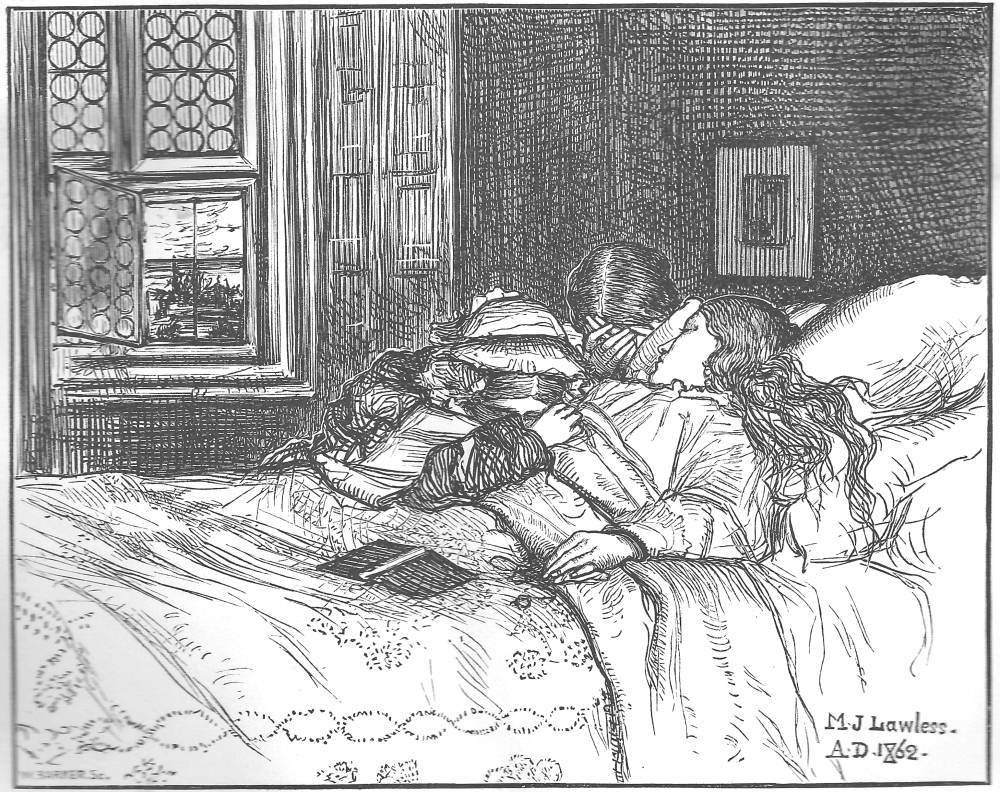

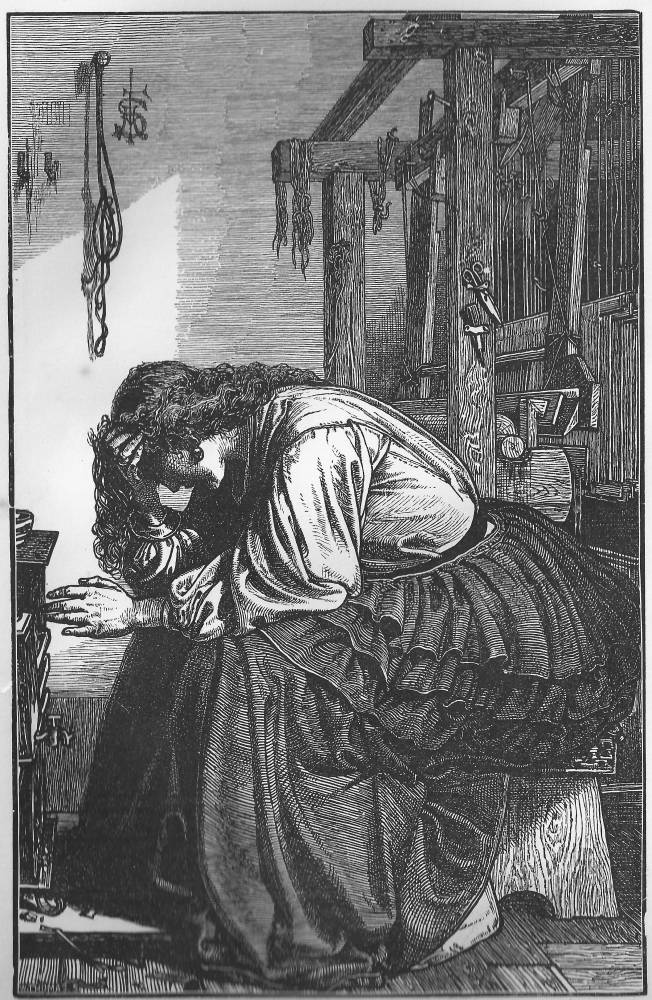

Left to right: (a) One Dead by M. J. Lawless. (b) The Waiting Time by Frederick Sandys. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

A good example is M. J. Lawless’s treatment of a conventional poem, ‘One Dead’. The verse celebrates a notion of fortitude in which the bereaved are resigned to the inevitability of a child’s death (p. 275). In the illustration, on the other hand, the focus is shifted from the aftermath of the girl’s death to the moment of her passing. The image represents the parents weeping over the body (facing p. 275), and the subject is their suffering rather than the poem’s moralising on faith. The only concession to religious symbolism is included in the form of the opened window, which, as in paintings such as Wallis’s The Death of Chatterton (1856; Tate Britain, London), is always a sign of the soul’s escape; but the scene is otherwise a tender dramatization of the immediacy of grief.

A parallel tendency to psychological realism is registered in an illustration by Sandys for ‘The Hardest Time of All’ (p. 91). The poem by Sarah Doudney to which it nominally responds is another piece of vague religiosity that reflects on the ‘silent resignation’ of waiting for death; but Sandys only uses this sentiment as a starting point for his own interpretation of the notion of ‘waiting’. Instead of dealing in abstractions, he personifies the idea of marking time in the form of an unemployed female weaver who is supposedly anticipating the next job but is really in the process of ‘waiting’ until she dies of starvation. Once again, the illustrator offers what seems a wilful contradiction of its source material: re-titling the image ‘The Waiting Time’ (facing p. 91), he imbues the anticipation of death with a raw, visceral, tragic intensity. With its bent head and outstretched hand this monumental figure is the very embodiment of universal suffering; reminiscent of Rethel’s morbid scenes of suffering and anguish (an influence to which Sandys elsewhere responds in illustrations such as ‘Until Her Death’ in Good Words), it is far from the usual pieties and seems incongruously placed in this type of magazine.

Indeed, ‘The Waiting Time’ can be read as a piece of polemic, showing not only a working-class character – a type generally missing from the magazine’s conservative pages – but specifically by presenting the viewer with an image of privation at the very moment when a slump in Lancashire was claiming the lives of hundreds. Framed by conventional expressions of faith and the timeless authority of God, Sandys intrudes a piece of hard-hitting social commentary, a topical exposè of current events which anchors its message in the harsh realities of the flesh, not the spirit. There is some concession to propriety by showing the weaver as if she were engaged in a cottage industry of the past rather than the mechanized production of the sixties; but the picture is still a startling indictment of the political situation of the here and now, questioning the role of Christian morality in a society based on laissez-faire capitalism. Famous for his visual outspokenness as much as for his sharp tongue, Sandys challenges the conservatism of Hogg’s bourgeois readership.

Hogg may not have understood the implications of such misalliances, and repeatedly displays a lack of editorial control; indeed, The Churchman’s Family Magazine unquestionably lacks cohesion. It tries to please diverse audiences, and it seems to want to combine the most conservative texts with illustrations which sometimes challenge both the source-material and its audience. Such incoherence is radically different from the sharp sense of purpose displayed in the tightly unified contents of Once a Week and The Cornhill Magazine. Both of these journals pull off the clever trick of giving miscellanea a controlled form in which the text and designs contribute to the effect as a whole. This does not happen in the case of The Churchman’s Family Magazine, and probably accounts, at least in part, for its early demise.

Works Cited

Churchman’s Family Magazine, The. London: Hogg, 1863–73.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s. Pinner: PLA; London: The British Library; Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

King, Edmund. Victorian Decorated Trade Bindings, 1830–1880. London: The British Library, 2003.

The Churchman’s Family Magazine. Publicity brochure. London: Hogg, 1865. Ephemera in the author’s collection.

White, Gleeson. English Illustration: The Sixties, 1855–70.London: Constable, 1897; reprint, Bath: Kingsmead, 1970.

Last modified 21 January 2013