I. Introduction

riting shortly before her death, Mary Augusta (Mrs Humphry) Ward gives us a memorable vignette of her early married days. She recalls how she and her husband would sit peacefully in different corners of the same small room in their Oxford house, studiously engaged amid their books, but at the same time exposed to a larger world of thought riven by "sharper antagonisms and deeper feuds than exist today." As she explains:

Darwinism was penetrating everywhere; Pusey was preaching against its effects on belief; Balliol stood for an unfettered history and criticism, Christ Church for authority and creeds; Renan's Origines [Ernest Renan's Histoire des Origines du Christianisme (1877)] were still coming out, Strauss's last book [David Strauss's Der alte und der neue Glaube (1872)] also; my uncle [Matthew Arnold] was publishing God and the Bible in succession to Literature and Dogma; and [Walter R. Cassels'] Supernatural Religion was making no small stir. [A Writer's Recollections, I: 220]

It is hard to imagine now the impact of this intellectual ferment on the sensitive individual operating in that milieu. When Ward herself attended a stern lecture by the High Church Reverend John Wordsworth, then Fellow and Tutor of Brasenose, and listened to him condemning as sinful those earnest thinkers whom she so much admired, she was incandescent. She wrote a pamphlet protesting against his views, and had it printed and displayed in a bookshop for distribution. It was soon removed but, according to John Sutherland, it cooked her husband's goose at Oxford (80), and, in a way, she got her own back by channelling her views much more dramatically into Robert Elsmere.

All this and more went into the following passage from Chapter 28 of the book, which she wrote after moving away from Oxford, and which became a phenomenal best-seller, provoking extraordinary interest. Although the Wards had a house in Bloomsbury, much of the novel was written while renting rooms at Borough Farm, near Milford in Surrey, and the title character is the Oxford-trained young Rector of Murewell, his parish set in recognisably local Surrey countryside. In this passage, he explains his new spiritual position to his wife Catherine. It is clear that his views have developed partly from working among the poor of Mile End — not the one in the East End of London, but a huddle of practically ruined labourers' cottages built on a swamp on the outskirts of his own parish, where the people are all afflicted by the damp, and disease. But his faith has also been shaken by others in his intellectual circle. His tutor at Oxford, Edward Langham, was one of these. In her introduction to the 1911 edition of the novel, Ward says that Langham's character was inspired by her work on Henri Frédéric Amiel's Journal Intime (I: xii); but Sutherland makes a plausible case for another model: Humphry Ward's close friend at Brasenose, Walter Pater. Robert has also been influenced by Professor Grey, a character through whom Ward pays tribute to her own mentor, Thomas Hill Green of Balliol (see Robert Elsmere, I: xli). Green is one of her two dedicatees. More recently, Robert has fallen under the sway of the local squire, with his well-stocked library. Squire Wendover, says Ward in her introduction, shares "some of his more obvious traits" with Mark Pattison, the Rector of Lincoln, and some of his exchanges with Robert go back to her own talks with Pattison during her early Oxford days (I: xx-xxi).

In the same introduction, Ward claims that the title character himself is "a figure of pure imagination" (I: xlii). But he seems to have been inspired by two people, Edward Denison (1840-1870), one of the founders of the Settlement movement, whose work in the East End probably hastened his early death from tuberculosis; and Humphry Ward's much-loved mentor, the historian John Richard Green (1837-1883), whose doubts had sent him in that direction too, sadly with similar results (see Sutherland 115). But there may well be an element here, as well, of the Rev. Stopforde Brooke, minister of the very chapel that the Wards attended in London, who had announced from the pulpit in 1880 "that he no longer believed in the Incarnation and was leaving the Church of England" (Ashton 286). Catherine, it seems, also has her origins in real life, in the young, delicate and sensitive Laura Lyttelton, to whom, as well as to Thomas Hill Green, Ward dedicated this, her most famous work (see Sutherland 110). But the point is not that Ward's figures were modelled on this or that particular individual or individuals, but that they represented the whole religious turmoil of the time. She herself once described the novel as, to some extent at least, "a study in Modernism" (A Writer"s Recollections, II: 99); and, as Joseph T. Altholz has observed, Robert Elsmere himself is "the type of many young men of the late nineteenth century, some maintaining an outward conformity while thinking freely, others leaving organized religion altogether."

II. Excerpt from Chapter Book IV, "Crisis," Chapter XXVIII

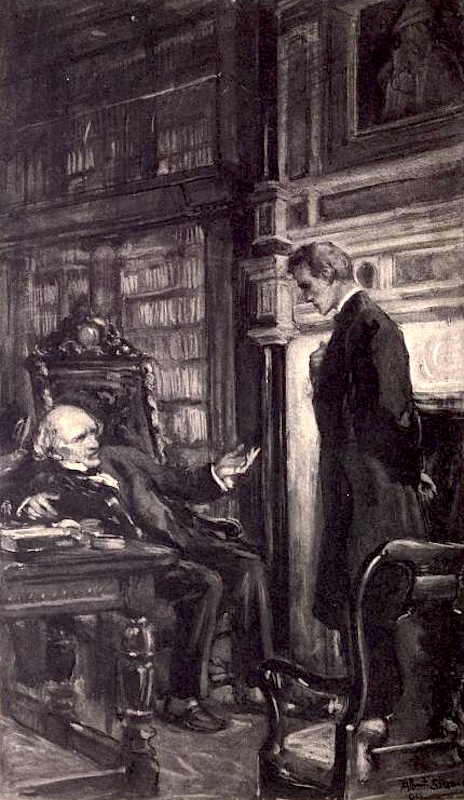

Left: Robert Elsmere with the Squire, by Albert Sterner (1863-1946). Source: frontispiece of Vol. II of the novel. Right: "Catherine Leyburn," also by Sterner. Source: frontispiece of Vol. I.

[Robert has come to the point where he can no longer keep his doubts to himself:]

For six or seven months, Catherine — really for much longer, though I never knew it — I have been fighting with doubt — doubt of orthodox Christianity — doubt of what the Church teaches — of what I have to say and preach every Sunday. First it crept on me I knew not how. Then the weight grew heavier, and I began to struggle with it. I felt I must struggle with it. Many men, I suppose, in my position would have trampled on their doubts — would have regarded them as sin in themselves, would have felt it their duty to ignore them as much as possible, trusting to time and God"s help. I could not ignore them. The thought of questioning the most sacred beliefs that you and I —" and his voice faltered a moment — "held in common, was misery to me. On the other hand, I knew myself. I knew that I could no more go on living to any purpose, with a whole region of the mind shut up, as it were, barred away from the rest of me, than I could go on living with a secret between myself and You. I could not hold my faith by a mere tenure of tyranny and fear. Faith that is not free — that is not the faith of the whole creature, body, soul, and intellect — seemed to me a faith worthless both to God and man!"

Catherine looked at him stupefied. The world seemed to be turning round her. Infinitely more terrible than his actual words was the accent running through words and tone and gesture — the accent of irreparableness, as of something dismally done and finished. What did it all mean? For what had he brought her there? She sat stunned, realizing with awful force the feebleness, the inadequacy, of her own fears.

He, meanwhile, had paused a moment, meeting her gaze with those yearning, sunken eyes. Then he went on, his voice changing a little.

But if I had wished it ever so much, I could not have helped myself. The process, so to speak, had gone too far by the time I knew where I was. I think the change must have begun before the Mile End time. Looking back, I see the foundations were laid in — in — the work of last winter."

She shivered. He stooped and kissed her hands again passionately. "Am I poisoning even the memory of our past for you?" he cried. Then, restraining himself at once, he hurried on again — "After Mile End you remember I began to see much of the Squire. Oh, my wife, don't look at me so! It was not his doing in any true sense. I am not such a weak shuttlecock as that! But being where I was before our intimacy began, his influence hastened everything. I don't wish to minimize it. I was not made to stand alone!"

And again that bitter, perplexed, half-scornful sense of his own pliancy at the hands of circumstance as compared with the rigidity of other men, descended upon him. Catherine made a faint movement as though to draw her hands away.

"Was it well," she said, in a voice which sounded like a harsh echo of her own, "was it right for a clergyman to discuss sacred things — with such a man?"

He let her hands go, guided for the moment by a delicate imperious instinct which bade him appeal to something else than love. Rising, he sat down opposite to her on the low window seat, while she sank back into her chair, her fingers clinging to the arm of it, the lamp-light far behind deepening all the shadows of the face, the hollows in the cheeks, the line of experience and will about the mouth. The stupor in which she had just listened to him was beginning to break up. Wild forces of condemnation and resistance were rising in her; and he knew it. He knew, too, that as yet she only half realized the situation, and that blow after blow still remained to him to deal.

"Was it right that I should discuss religious matters with the Squire?" he repeated, his face resting on his hands. "What are religious matters, Catherine, and what are not?"

Then still controlling himself rigidly, his eyes fixed on the shadowy face of his wife, his ear catching her quick uneven breath, he went once more through the dismal history of the last few months, dwelling on his state of thought before the intimacy with Mr. Wendover began, on his first attempts to escape the Squire's influence, on his gradual pitiful surrender. Then he told the story of the last memorable walk before the Squire's journey, of the moment in the study afterward, and of the months of feverish reading and wrestling which had followed. Half-way through it a new despair seized him. What was the good of all he was saying? He was speaking a language she did not really understand. What were all these critical and literary considerations to her?

The rigidity of her silence showed him that her sympathy was not with him, that in comparison with the vibrating protest of her own passionate faith which must be now ringing through her, whatever he could urge must seem to her the merest culpable trifling with the soul's awful destinies. In an instant of tumultuous speech he could not convey to her the temper and results of his own complex training, and on that training, as he very well knew, depended the piercing, convincing force of all that he was saying. There were gulfs between them — gulfs which as it seemed to him in a miserable insight, could never be bridged again. Oh! the frightful separateness of experience!

Still he struggled on. He brought the story down to the conversation at the Hall, described — in broken words of fire and pain — the moment of spiritual wreck which had come upon him in the August lane, his night of struggle, his resolve to go to Mr. Grey. And all through he was not so much narrating as pleading a cause, and that not his own, but Love's. Love was at the bar, and it was for love that the eloquent voice, the pale varying face, were really pleading, through all the long story of intellectual change.

At the mention of Mr. Grey, Catherine grew restless, she sat up suddenly, with a cry of bitterness.

"Robert, why did you go away from me? It was cruel. I should have known first. He had no right — no right!"

She clasped her hands round her knees, her beautiful mouth set and stern. The moon had been sailing westward all this time, and as Catherine bent forward the yellow light caught her face, and brought out the haggard change in it. He held out his hands to her with a low groan, helpless against her reproach, her jealousy. He dared not speak of what Mr. Grey had done for him, of the tenderness of his counsel toward her specially. He felt that everything he could say would but torture the wounded heart still more.

But she did not notice the outstretched hands. She covered her face in silence a moment as though trying to see her way more clearly through the maze of disaster; and he waited. At last she looked up.

"I cannot follow all you have been saying," she said, almost harshly. "I know so little of books, I cannot give them the place you do. You say you have convinced yourself the Gospels are like other books, full of mistakes, and credulous, like the people of the time; and therefore you can't take what they say as you used to take it. But what does it all quite mean? Oh, I am not clever — I cannot see my way clear from thing to thing as you do. If there are mistakes, does it matter so — so — terribly to you?" and she faltered. "Do you think nothing is true because something may be false? Did not — did not — Jesus still live, and die, and rise again? — can you doubt — do you doubt — that He rose — that He is God — that He is in heaven — that we shall see Him?"

She threw an intensity into every word, which made the short, breathless questions thrill through him, through the nature saturated and steeped as hers was in Christian association, with a bitter accusing force. But he did not flinch from them.

"I can believe no longer in an incarnation and resurrection," he said slowly, but with a resolute plainness. "Christ is risen in our hearts, in the Christian life of charity. Miracle is a natural product of human feeling and imagination and God was in Jesus — pre-eminently, as He is in all great souls, but not otherwise — not otherwise in kind than He is in me or you."

His voice dropped to a whisper. She grow paler and paler.

"So to you," she said presently in the same strange altered voice, "my father — when I saw that light on his face before he died, when I heard him cry, "Master, I come!" was dying — deceived — deluded. Perhaps even," and she trembled, "you think it ends here — our life — our love?"

It was agony to him to see her driving herself through this piteous catechism. The lantern of memory flashed a moment on to the immortal picture of Faust and Margaret. Was it not only that winter they had read the scene together?

Forcibly he possessed himself once more of those closely locked hands, pressing their coldness on his own burning eyes and forehead in hopeless silence.

"Do you, Robert?" she repeated insistently.

"I know nothing," he said, his eyes still hidden. "I know nothing! But I trust God with all that is clearest to me, with our love, with the soul that is His breath, His work in us!"

The pressure of her despair seemed to be wringing his own faith out of him, forcing into definiteness things and thoughts that had been lying in an accepted, even a welcomed, obscurity.

She tried again to draw her hands away, but he would not let them go. "And the end of it all, Robert?" she said — "the end of it?"

Never did he forget the note of that question, the desolation of it, the indefinable change of accent. It drove him into a harsh abruptness of reply —

"The end of it — so far — must be, if I remain an honest man, that I must give up my living, that I must cease to be a minister of the Church of England. What the course of our life after that shall be, is in your hands — absolutely."

She caught her breath painfully. His heart was breaking for her, and yet there was something in her manner now which kept down caresses and repressed all words.

Suddenly, however, as he sat there mutely watching her, he found her at his knees, her dear arms around him, her face against his breast.

"Robert, my husband, my darling, it cannot be! It is a madness — a delusion. God is trying you, and me! You cannot be planning so to desert Him, so to deny Christ — you cannot, my husband. Come away with me, away from books and work, into some quiet place where He can make Himself heard. You are overdone, overdriven. Do nothing now — say nothing — except to me. Be patient a little and He will give you back himself! What can books and arguments matter to you or me? Have we not known and felt Him as He is — have we not, Robert? Come!"

She pushed herself backward, smiling at him with an exquisite tenderness. The tears were streaming down her cheeks. They were wet on his own. Another moment and Robert would have lost the only clew which remained to him through the mists of this bewildering world. He would have yielded again as he had many times yielded before, for infinitely less reason, to the urgent pressure of another's individuality, and having jeopardized love for truth, he would now have murdered — or tried to murder — in himself, the sense of truth, for love.

But he did neither.

Holding her close pressed against him, he said in breaks of intense speech: "If you wish, Catherine, I will wait — I will wait till you bid me speak — but I warn you — there is something dead in me — something gone and broken. It can never live again — except in forms which now it would only pain you more to think of. It is not that I think differently of this point or that point — but of life and religion altogether. — I see God"s purposes in quite other proportions as it were. — Christianity seems to me something small and local. — Behind it, around it — including it — I see the great drama of the world, sweeping on — led by God — from change to change, from act to act. It is not that Christianity is false, but that it is only an imperfect human reflection of a part of truth. Truth has never been, can never be, contained in any one creed or system!"

She heard, but through her exhaustion, through the bitter sinking of hope, she only half understood. Only she realized that she and he were alike helpless — both struggling in the grip of some force outside of themselves, inexorable, ineluctable.

Robert felt her arms relaxing, felt the dead weight of her form against him. He raised her to her feet, he half carried her to the door, and on to the stairs. She was nearly fainting, but her will held her at bay. He threw open the door of their room, led her in, lifted her — unresisting — on to the bed. Then her head fell to one side, and her lips grew ashen. In an instant or two he had done for her all that his medical knowledge could suggest with rapid, decided hands. She was not quite unconscious; she drew up round her, as though with a strong vague sense of chill the shawl he laid over her, and gradually the slightest shade of color came back to her lips. But as soon as she opened her eyes and met those of Robert fixed upon her, the heavy lids dropped again.

"Would you rather be alone?" he said to her, kneeling beside her.

She made a faint affirmative movement of the head and the cold hand he had been chafing tried feebly to withdraw itself. He rose at once, and stood a moment beside her, looking down at her. Then he went. [II: 119-27]

III. Commentary

he obvious conflict here is between faith and doubt. In the face of her husband's revelations, Catherine's own faith is utterly, even defiantly, unchanged. "Did not — did not — Jesus still live, and die, and rise again? — can you doubt — do you doubt — that He rose — that He is God — that He is in heaven — that we shall see Him?" The short questions are rhetorical, rising challengingly to Robert in a crescendo of conviction, ending with the emphatic "Him." But Robert does doubt. His faith, in fact, has been irretrievably shattered. Intellectually persuaded by his various mentors and his own reading (guided by them) that the gospels are, in Catherine's words, "full of mistakes, and credulous, like the people of the time," he can no longer believe that God was in Jesus "otherwise in kind than he is in me or you." As Gladstone was to say in his searching review of the book, this calls into question, indeed destroys, the whole Christian scheme of the Incarnation and Redemption. Therefore, Robert tells Catherine, "there is something dead in me — something gone and broken. It can never live again — except in forms which now it would only pain you more to think of." In contrast to hers, his words are flat, toneless, final.

This fundamental difference is greatly complicated by the tension between love and a sense of betrayal on Catherine's part, and conscience and love on Robert's. Catherine cannot understand why her husband turned to the squire and Grey instead of to her. The former is not only a sceptic, but inhumane: he had not bothered with his tenantry, had indeed deliberately turned a blind eye to their misery for thirty years, until Robert came along and forced things to a climax. So "was it right for a clergyman to discuss sacred things — with such a man?" Catherine asks. Reviewing the novel, the American social reformer Julia Ward Howe asks the same question, but for a different reason. Wendover "seems to have pursued his researches with great intellectual honesty," she admits, "but with no touch of religious affection. Hence, his influence was one which Elsmere should not have invited" (112). Catherine is the one with "religious affection," which she expresses so movingly here. But, she says, "I know so little of books," and the kind of simple "trust" she has is not enough for her husband. His thirst for knowledge is too great for him to be satisfied with something so unquestioning. The battle for him now, as he sees it, is between his conscience and his heart. At first he almost yields to her request to go into retreat for a while, "into some quiet place where He can make Himself heard," but "having jeopardized love for truth," he cannot now murder (and he does put it that violently) "the sense of truth, for love."

Robert's admission here that he has "yielded before, for infinitely less reason, to the urgent pressure of another's individuality," chimes with Sutherland's criticism that he comes across in the earlier parts as "weak and somewhat epicine" (121). There is something in the young man of his author, who had sat eagerly at the feet of those she considered to have superior intellects, especially Pattison. Even in the previous chapter, Robert had recognised how easily he had been manipulated by the squire, even though he feels that the older man (like Langham) had only accelerated a process that had already begun in him. Evolution, for example, had begun to "press, to encroach, to intermeddle with the mind's other furniture" (I: 498). But, anyway, he has made up his mind now. For him, the die is cast. His conscience demands that he should give up his living and "cease to be a minister of the Church of England," and that is exactly what he does.

This intense central episode confirms his now unwavering resolve, but, more than any other interview in this novel of ideas, reveals the cost of it in terms of Robert's personal life, both for him and his wife. Some of the intensity here may have come from Ward's imagining some such scenes between her own parents, when her father Thomas Arnold communicated his own crises of faith to her mother Julia. In her father's case the problem had been not a loss of faith, but vacillation between the established church and Catholicism; but that had been difficult and dramatic enough at the time. At any rate, the dialogue between the Elsmeres at this point is both natural and, in contrast to Robert's earlier discussions with his mentors, affecting. In juxtaposing Catherine's unchanged, steady faith in a personal saviour with her husband's new but finally settled scepticism, Ward has, however, underplayed Catherine's intellectual capacity. Note that Albert Sterner's frontispiece to the first volume shows her looking up thoughtfully for a book, and we are told in this first volume that her favourite work is Augustine's Confessions (I: 475), hardly the reading matter of one who knows or thinks little of books. This relegation of Catherine to the realm of the emotions may be an early indication of the leading role Ward was about to take in the Anti-Suffrage movement. Still, it is in the couple's confrontation here, more than anywhere else in the novel, that Ward succeeds in bringing out the human drama of "the clash of older and younger types of Christianity" (Beauman 138).

Related Material

- The Warfare of Conscience with Theology in Victorian Britain

- The Higher Critics (including Strauss)

- I. Ward's Childhood and Early Married Life

- II. Ward's Writing Career

- III. Ward's Philanthropy and Public Life

- IV. Ward's Death and Later Reputation

- Does Mary Ward really relegate Catherine "to the realm of the emotions" at the end of Robert Elsmere?

Sources

Ashton, Rosemary. Victorian Bloomsbury. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2012. Print.

Albert Sterner. Singular Impressions. Web. 6 November 2013.

Beauman, Katherine Bentley. Women and the Settlement Movement. London: Radcliffe Press (I. B. Tauris imprint), 1996. Print.

Gladstone, W. E. "Robert Elsmere" and the Battle of Belief. New York: Anson D. F. Randolph, [1888]. Internet Archive. Web. 6 November 2013.

Howe, Julia Ward. Review in "Robert Elsmere's Mental Struggle." The North American Review, 1 Jan, 1889. 119-127. Internet Archive. Web. 6 November 2013.

"Mrs Humphry Ward: Her Art as a Novelist. Public-Spirited Activities." Times. 25 March 1920, p. 16. Times Digital Archive. Web. 6 November 2013.

Sutherland, John. Mrs Humphry Ward: Eminent Victorian, Pre-Eminent Edwardian. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990. Print.

Trotter, W. R. The Hilltop Writers. Headley Down, Hampshire: John Owen Smith, 2003. See pp. 210-12. Print.

Ward, Mrs Humphry. Robert Elsmere. Vol. I. New York and London: Harper, 1918. Internet Archive. Web. 6 November 2013.

_____. Robert Elsmere. Vol. II. New York and London: Harper, 1918. Internet Archive. Web. 6 November 2013.

_____. A Writer"s Recollections. Vol. I. New York and London: Harper, 1918. Internet Archive. Web. 6 November 2013.

_____. A Writer"s Recollections. Vol. II. New York and London: Harper, 1918. Internet Archive. Web. 6 November 2013.

Last modified 3 November 2013