The Battle of Life and The Haunted Man were deservedly less successful in their own time and have only the interest now of being quarries in their rather peculiar stories for autobiographical obsessions. — Angus Wilson, The World of Charles Dickens, p. 181.

nfortunately, until

recently, Angus Wilson has been quite correct about the critical reception of Dickens's

last Christmas Book, although in popular terms it was as successful as any of the others,

selling 18,000 copies on the day of its publication. None of the many Dickens biographers

and only a handful of his modern critics have taken the trouble to analyze the novella as

a deliberate, tightly-structured work of art rather than a mere "biographical quarry."

This neglect is in marked contrast to the ever-growing pile of essays, commentaries, and

even whole books on the progenitor of the Christmas Books, A Christmas Carol (1843).

nfortunately, until

recently, Angus Wilson has been quite correct about the critical reception of Dickens's

last Christmas Book, although in popular terms it was as successful as any of the others,

selling 18,000 copies on the day of its publication. None of the many Dickens biographers

and only a handful of his modern critics have taken the trouble to analyze the novella as

a deliberate, tightly-structured work of art rather than a mere "biographical quarry."

This neglect is in marked contrast to the ever-growing pile of essays, commentaries, and

even whole books on the progenitor of the Christmas Books, A Christmas Carol (1843).

During the summer of 1846, Dickens reported to John Forster that he had been seized by a weird, ghostly idea for a Christmas book — but it was September, 1847, before Forster received any slips. Finally, with Dombey and Son out of the way, Dickens took up the idea again in August, 1848. During this period of his life, Dickens had become more and more about the secret of his past, his father's being in the Marshalsea, while he worked at Warren's Blacking, 30 Hungerford Stairs, on the Thames. He made an attempt to confront this late childhood trauma in an abortive autobiography, My Early Times, which was not published until Forster's Biography. Although Dickens mined these five manuscript pages for David Copperfield's childhood story (May 1849), the blacking factory incident remained a secret between himself and Forster until Dickens's death in 1870.

The reclusive, cynical professional man who is the protagonist of The Haunted Man is not a businessman like the first Christmas Book protagonist, but he is as lonely in his academic study as Scrooge is in his counting-house. And Professor of Chemistry, Mr. Redlaw, too, is haunted by a similar sorrow: the death of a beloved sister. The gloomy, alienated intellectual of this novella bears a name which seems to anticipate both the Tennyson's phrase "Nature, red in tooth and claw" from In Memoriam, lvi (1850), and Darwin's thesis about "survival of the fittest" in Origin of Species (1859), although Dickens probably intended it as an allusion to the eye-for-an-eye ethic of the Old Testament, as opposed to the central doctrines of repentance and forgiveness in the New Testament, doctrines that the action of the story compels Redlaw to apply to himself. A phantom, a bad angel or spiritual alter-ego — indeed, Dickens uses such terms as "phantom" (36 times), "shadow" (14 times), and "shade" (five times) much more often than "ghost" (eight times) to describe this döppelganger — when requested agrees to cancel all of Redlaw's painful memories at the close of Part One. Although Dickens was fascinated by the German Romantic genre of the ghost story and wrote a baker's dozen of them himself, mostly in the humorous-satirical and allegorical modes, he was nevertheless rather skeptical about such entities in real life:

Doubtful and scant of proof at first, doubtful and scant of proof still, all mankind's experience of them is, that their alleged appearances have been, in all ages, marvellous, exceptional, and resting on imperfect ground proof; that in vast numbers of cases they are known to be delusions superinduced by a well understood and by no means uncommon disease . . . . ("Dickens on Ghosts," 7)

Dickens whimsically attributes the German spirit of the

In Part Two, Redlaw realizes his mistake because the cancellation of such memories has also cancelled similar memories for those whom he touches. At his lowest ebb, as incapable of human sympathy as "a man turned to stone" (Part 3) — perhaps an oblique allusion to the Mosaic tablets of the law, hearing Christmas music, Redlaw begins to recover through the agency of the angelic Milly Swidger, an emotional, unintellectual, humble but caring woman who has lost her only child. Like the traditional music of the season which the early Victorian churches were reviving in the 1840s, Milly represents the benevolent effects of memory, underscored by the last words of the tale: "Lord, keep my Memory Green."

As Stanley Tick has remarked, "How blatant the didacticism seems! But a modern, psycho-biographical perspective makes this last Christmas Book intelligible." The "Dismal Man" in the fifth chapter of The Pickwick Papers is a similar character, for his gloominess is related to a childhood experience. The same sentiment is expressed more confidently and humorously through Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, who as an infant lost his mother and was rejected by his unforgiving father, and now freezes everyone else out of his private life.

There is little of the Carol's or The Chimes' gusto in this novella's happy ending, despite Redlaw's coming to terms with his past. In taking itself so seriously, in its rhetorical convolutions, and in its bright but cynical protagonist, The Haunted Man anticipates another short novel a decade later: A Tale of Two Cities. Both books share the motif of the terrible secret from the past that blights the present, especially for the story's melancholy professional, and of that alienated individual's redemption through love. But, then, aren't Professor Redlaw, attorney Sydney Carton, novelist David Copperfield, and even businessman Philip Pirrip all reflections of the discontented, middle-aged writer that the quondam "Fielding of the Nineteenth Century" became by the close of the 1840s?

Although the critical reception of the last of the Christmas Books of Charles Dickens was, as Michael Slater remarks, "very mixed, with hostile predominating" ( CB II, 237), with its charming red cover, gilt lettering, and abundant illustrations by a talented team of first-rate artists, Dickens was able to announce the immensely satisfying figure of 18,000 in advance sales to Thomas Beard on 19 December, 1848. After a lapse of two years, Dickens was back on the Christmas market with a vengeance, despite a lukewarm response to The Battle of Life (19 December, 1846). In some cases 1846's little scarlet book, lavishly illustrated with thirteen plates by four well-known artists (Daniel Maclise, Clarkson Stanfield, Richard Doyle, and once again John Leech) was greeted with what amounts to critical ridicule: on Christmas Eve, 1848, The Morning Chronicle had pronounced it "exaggerated, absurd, impossible sentimentality." However, in part owing to the reputation established by its predecessors, it sold 23,000 copies on the day of its publication (as opposed to the record of 6,000 set by A Christmas Carol itself three years earlier, although according to Forster by the time New Year's Day of 1844 had arrived Chapman and Hall had sold 15,000 copies in total). In the 1846 seasonal offering Dickens had abandoned the allegorical flavour, "the explicit social criticism" (Guida 149), and the supernatural machinery common to A Christmas Carol (1843), The Chimes (1844), and The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), subsequently much-dramatised. Now, after an enforced absence of two Christmases, he reverted to these narrative features and strategies, albeit with a less heart-warming curmudgeon than Ebenezer Scrooge, Trotty Veck, John Peerybingle, or Dr. Jeddler as his protagonist.

Dickens learned two valuable lessons from his 1846 Christmas book failure, The Battle of Life: unless he was really inspired, as in the case of A Christmas Carol, he could not successfully plot a work of that length without using supernatural machinery to manipulate the change of heart inherent to his purpose in the Christmas books . . . . . Here Dickens returned to the themes, structure, and strategies of A Christmas Carol, and while it is in no way the masterpiece that the Carol undoubtedly is, to modern readers it is more interesting and complex than the intervening three books. In its exegesis of the role memory in shaping a character's moral fiber, and in its cohesive and economical plot, it both emulates the Carol and anticipates the novels which succeeded it. (Glancy, DSA 15: 65)

Consistently throughout the Christmas Books Dickens had adhered to the tight form of the novella, with a main and a subplot, a limited cast of characters, highly individualized dialogue, and a programme of illustration which he had both orchestrated and conducted, as his letters to the various artists reveal. The whole series involves fifty-seven plates and seven artists in all:

- A Christmas Carol (1843): 8 plates by John Leech

- The Chimes (1844) 13 plates: D. Maclise (2), R. Doyle (4), C. Stanfield (2), and J. Leech (5)

- The Cricket on the Hearth (1845) 14 plates: D. Maclise (2), R. Doyle (3), C. Stanfield (1), E. Landseer (1), and J. Leech (7)

- The Battle of Life (1846) 13 plates: D. Maclise (4), R. Doyle (3), C. Stanfield (3), and J. Leech (3)

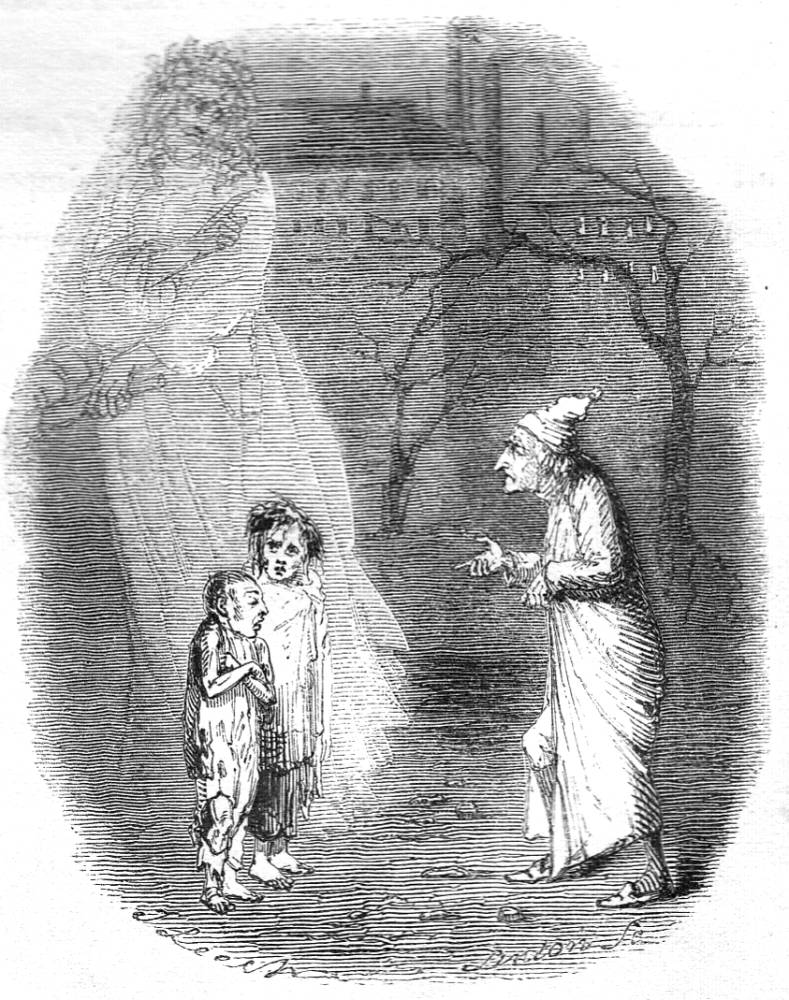

- The Haunted Man (1848) 17 plates: Sir John Tenniel (6), Frank Stone (3), C. Stanfield (3), and J. Leech (5).

Seven of the illustrations to The Haunted Man were provided by two of Dickens's Christmas Book regulars, Leech and Stanfield, but Maclise and Doyle did not contribute. In their place appeared three drawings by the self-taught artist Frank Stone (father of Marcus Stone, who was to illustrate Our Mutual Friend) who had been friendly with Dickens since they met in the Shakespeare Club in 1838-39; and five drawings by John Tenniel who later took Doyle's place on Punch and achieved fame through his illustrations for Lewis Carroll. (Slater, II: 236)

Whereas A Christmas Carol, more modestly illustrated with eight plates by a single artist, did not even contain a list of illustrations, the remaining Christmas Books had emphasized the pictorial element. In a sense, the second in the series, The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Ran an Old Year Out and a New Year In, had set the visual pattern for the series, having thirteen plates (ten of them dropped into the text as a stunning synthesis of pictorial and textual narratives) by four accomplished artists. This team approach Dickens had inaugurated almost certainly to ensure that all plates would be ready in time for the December publication date. His illustrators were busy in those days, working for Punch and other illustrated magazines, as well as working on other writers' books. Despite the fact that the illustrations added considerably to the purchase price of Dickens's annual Christmas offering (especially if these were hand-coloured) and would thereby decrease his profits (as was very much the case with the Carol five years earlier), Dickens did not merely maintain the programme of illustration that accompanied previous Christmas Books; he expanded it. Now, for The Haunted Man Dickens devised a lavish programme of seventeen plates, with Tenniel and Leech leading, and Stone and Stanfield supporting. Clearly Dickens placed great confidence in Leech throughout the Christmas Books, for he produced 44% of the total illustrations (28 out of 65 plates). Through his Pickwick illustrator George Cruikshank in July, 1836, while with Bentley's Miscellany, Dickens met John Leech, recommending him to Chapman and Hall for their Library of Fiction. With the exception of Tenniel, the artists were all close friends of Dickens well before he commenced writing The Haunted Man in the summer of 1847. Dickens first became acquainted with Stanfield in December, 1837, and with Stone, Secretary of the Shakespeare Society, in March, 1838. Dickens's 30 October, 1848, letter to Leech indicates that the leading Christmas Book illustrator had yet to meet Tenniel at that point, and, indeed, that thirty-six-year-old Dickens himself had just met the twenty-eight-year-old Tenniel:

Mr. Tenniel has been here today and will go to work on the frontispiece. We must arrange for a dinner here [Devonshire Terrace], very shortly, when you and he may meet. He seems to be a very agreeable fellow, and modest. (Pilgrim Letters 5: 431)

Tenniel (1820-1914) was some three years younger than Leech (1817-64) and considerably younger than Stanfield (1793-1867), but had already exhibited at the Society of British Artists in 1836 and at the Royal Academy (1837-42). Since Dickens's usual engraver, L. C. Martin (whose firm was responsible for seven of the 17 Haunted Man plates) was married to Tenniel's sister, it is surprising that Dickens and Tenniel had not met sooner. The year after illustrating The Haunted Man, Tenniel replaced Richard Doyle on the staff of Punch when the latter left because as a Catholic he objected to the magazine's attacks on the papacy. Dickens, not yet aware of Tenniel's capabilities, confined him to ornamental subjects (the frontispiece, the title-page, and the fire-side scene that opens the story proper), and gave over to him what Leech had not the time for, resulting in the extremely wooden renditions of Mrs. Tetterby and her brood, a muffled Redlaw, and Leech's The Boy before the Fire in "The Gift Diffused" (Ch. 2).

J. A Hammerton explains why, despite their long-standing friendship (which included a trip to Cornwall together in 1843) and Stanfield's brilliant theatrical scenery painting, especially of seascapes, Dickens did not entrust a larger share of any of the Christmas Book illustrated programmes to him. "He contributed to the whole series with the exception of the first, and his drawings, of a quiet and somewhat conventional type, if they did not add to the humour of the stories — he was never guilty of attempting the comic — certainly enriched the artistic side of the book" (15).

In "To Frank Stone" (21 Nov., 1848), Dickens gives Stone a list of subjects from which to choose for Chapter Two: "you should keep Milly, as you have begun with her" suggests that the writer is concerned with pictorial-narrative continuity. Stone's sequence follows Milly Swidger (wearing the same dress in each); Milly and the Old Man, Milly and the Student, and Milly and the Children"all executed with that firmness of line and Giotto-like solidity of figure for which his work was known. Milly is the central figure in each half-page illustration. On November 23, writing from Brighton, Dickens applauds Stone's first picture in the sequence:" The drawing of Milly on the chair [hanging holly with her father-in-law, Philip] is charming" (the last word twice underlined). However, Dickens is already formulating plans to use her as the counter-touchstone to Redlaw's Midas touch, and insists she be given a matronly cap to add to her age and dignity:

There is something coming in the last part, about her having had a dead child, which makes it yet more desirable than the existing text does, that she should have that little matronly sign about her. — Unless the artist is obdurate indeed, and then he'll do as he likes. (Pilgrim Letters 5: 446)

With what a subtle hand the charioteer directs his proud steeds, always suggesting and pointing through praise, but never commanding!

Meantime, publication day drawing ever nearer and the bulk of the work depending upon the ever-busy Leech, Dickens had written him from Devonshire Terrace before departing for Brighton, urging haste: "With a Stick" (22 Nov., 1848) underlined. Although Dickens feels that "speed is now of transcendent importance" (the latter two words doubly underlined), he still manages his leading horse with a gentle hand: "Your illustrations in the second part will be, I suppose, the Tetterby family and the boy by the fire. Unless anything else should strike you particularly." In fact, to maintain visual continuity, Leech had to continue as he had begun, working on the character studies of Redlaw, the Phantom, the Boy, the Tetterbys in general and Johnny with the gigantic baby whom the little wag has dubbed "Moloch" (the Canaanite devourer of childhood). The writer correctly assessed Leech's strength as comedy from the first, and steered him towards the petit bourgeois family of newsvendors who are The Haunted Man's equivalents of the Carol's Cratchits, representing a class and a social group so well known to the writer, his own family when he was a child. "Bradbury told me you wished to do some comedy" he wrote to Leech on 1 December, 1848." You will find plenty of bits, I trust, in connexion with the Tetterby family" (Letters 5: 452), he reiterates, having already mentioned that boisterous troop a week earlier to Leech. In the earlier letter," Early next week, I will describe the large illustration of the dinner to you" (Letters 5: 444) suggests that Dickens is outstripping the ability of his publishers to generate proofs with which Dickens has hitherto supplied his artists. However, undoubtedly concerned that Punch business is pressing Leech, Dickens sent the artist a letter via his publisher, William Bradbury, from the Bedford Hotel, Brighton, "explaining that not knowing how his time may serve, I have given the dinner subject to Stanfield" (Letters 5: 451), who in the last plate of The Haunted Man has emphasized "the Great Hall" at the expense of "The Christmas Party." Architectural elements — Gothic beams and an elegant stained glass window in the rear, overwhelm the diners, a number of whom are obscured or have their backs to the viewer, and who are a mere handful compared to the legions of Swidgers, who "were so numerous that they might join hands and make a ring round England" (351), "by dozens and scores" (352), to say nothing of the Tetterby clan.

The jollity of Scrooge's Christmas prize-turkey, punch, and polkas has boiled down to beef (which Stanfield indicates is something like a multi-layered cake with white icing!), around which somber "party-goers" chat rather than dance. The only spirits we are ever to credit fully in the Christmas Books in general and The Haunted Man are those of familial conviviality, charity, forgiveness, and compassion for our fellow man: in short, the Christmas Spirit. Sadly, in part owing to Stanfield's deficiencies and in part to a growing want of something in Dickens's own life, the bonhomie that attends the close of each of the other Christmas Books seems lacking here.

Harry Stone identifies the culmination of A Christmas Carol as "Scrooge's redemption (and our enlightenment)" (p. 14). The Carol's spirits or ghosts, like the Phantom in The Haunted Man, are both supernatural agents and allegorical figures helping to effect this redemption and social reintegration. Like Redlaw, "Scrooge assures us that we can advance from the prison of the self to the paradise of community" (p. 17). The term "imprisoned" actually occurs at the close of The Haunted Man with reference to Redlaw's kindlier, gentler side as " the dove so long imprisoned in his solitary ark might fly for rest and company" — for social integration ("Milly the embodiment of his better wisdom") and away from self-imposed alienation ("the Ghost . . . but the representation of his gloomy thoughts"). This theme in The Haunted Man Dickens makes explicit as Redlaw adopts the young student and his fiancée as his own children:

Then, as Christmas is a time in which, of all times in the year, the memory of every remediable sorrow, wrong, and trouble in the world around us, should be active with us, not less than our own experiences . . . . ("The Gift Reversed," 351)

Through seeing the effects of his doctrine "born bad" carried to extremes, Trotty Veck in The Chimeshad repented of his misanthropy just as Scrooge, having witnessed the inevitable outcome of his continually pushing away all emotional contact, rejoins the human family, as represented by Nephew Fred and the Cratchits; so in The Haunted Man Redlaw is reintegrated by acknowledging the restorative power of memory and the emotional necessity for human warmth and the cultivation of the inner life. Dickens had outlined this theme in his 21 November, 1848, letter to John Forster:

my point is that bad and good are inextricably linked in remembrance, and that you could not chooser the enjoyment of recollecting only the good. To have all the best of it you must remember the worst also. (Letters 5: 443)

Redlaw, initially a disappointed but successful man of middle-age, discovers that deprived of all memory, he has become " a man without a soul, as incapable of compassion, artistic sensitivity or spiritual understanding as the abandoned waif whose neglected short life is equally barren of memories" (Glancy, "Dickens and Christmas," 57). Only the street urchin (derived from the Carol's Ignorance and Want, but less allegorical and more insistently real), almost an animal because unaffected by any sentiment and actuated only by the Darwinian instinct for self-preservation, and the tender-hearted Milly are immune to Redlaw's touch. In fact, owing to her own deeply-felt sorrow, Milly is unconsciously able to counteract Redlaw's malignant "gift." Dickens wrote Miss Coutts concerning "a little notion for the book" on 6 November, 1848; this the editors of the pilgrim edition of the Letters have taken to mean

the softening effect of the Christmas music on Redlaw at the beginning of chapter three, but [to Ruth Glancy in "Dickens at Work"] it seems more likely that Dickens means Milly's stillborn child, who has such a good influence on her life, and is in fact chiefly the cause of her compassion which proves to be the antidote to Redlaw's curse and thus an essential part of the plot. The dead-born child does appear in Dickens's first page of rough notes. . . . (DSA 15: 73)

Is it too improbable to think of that dead child as young Charles Dickens, dead to his family in the Marshalsea, without caste and hope, working in the blacking factory? Or that the dead child represents his abortive attempt to write an autobiography? Dickens in the next decade would experience the death of a literal child himself, Dora, for whose death he felt responsible because he had made the fatal error of naming her after one of his characters (the heroine of his quasi-autobiography, David Copperfield, the book he wrote immediately The Haunted Man), and thereby crossing the line between his fictional and his real children?

The theme itself revolves around Dickens's belief that memory is a softening and chastening power, that the recollection of old sufferings and old wrongs can be used to touch the heart and elicit sympathy with the sufferings of others. . . . . For it was his suffering and the memory of his sufferings which had given him the powerful sympathy of the great writer, just as his recollection of those harder days inspired him with that pity for the poor and the dispossessed which was a mark of his social writings. (Ackroyd, 553)

Although biographer Fred Kaplan is correct in his contention that in The Haunted Man Dickens moves away from the domestic sentiment and communal cheer of the previous Christmas Books, his interest in psychology and the double or doppelganger are nothing new: Marley, for example, is as much Scrooge's double as the Phantom is Redlaw's. However, the Phantom is also a plot vehicle:

He is Mr. Hyde to Redlaw's Dr. Jekyll, and provides Dickens an essential and appropriate short cut in representing an internal dialogue, just as Redlaw's supernatural powers, his baneful, Midas-touch, provides an essential short cut — essential in so short a book — for representing his influence upon others.

And the boy labelled "Ignorance" in A Christmas Carol, what has he become? He has become in The Haunted Man a clearly recognizable savage slum child. There are no labels to be seen on his ragged clothes . . . . (Butt 147)

We have passed from the obvious allegory of A Christmas Carol and The Chimes to something more subtle. From 1850, Dickens would continue to offer his seasonal helping of humour, pathos, and preachment in the collaborative "framed-tales" of Household Words and its successor All the Year Round, a Christmas blend he was certain suited the popular if not the critical taste. However, perhaps in part owing to the new influence of Wilkie Collins, in these "somethings" for Christmas realism would predominate over allegory. Perhaps another impetus towards realism that Dickens received was delivered to him by his periodical critics, who resented the religious tone and pious sentimentalizing in which he indulges at the close of The Haunted Man. For example, an anonymous reviewer in Macphail's Edinburgh Ecclesiastical Journal for January, 1849, finds Mr. Dickens unfit as a yuletide preacher: "He does not grace the chair of national instructionñhe is both too tiny and too playful" (Dickens The Critical Heritage 180). The panning concludes by damning with faint praise:

Had it not been for the very handsome exterior and the high price [five shillings, the price of each of The Haunted Man's progenitors] of this new Christmas book of Mr. Dickens, it was only worthy of appearing in the window of the small shop of Tetterby & Co., the news-vendor, whom it celebrates. Let us now have a few more returns of Christmas, and Mr. Dickens will have destroyed his reputation as a tale-writer. We earnestly recommend him to quit the twenty-fifth of December, and take to the first of April. (181)

Dickens could have gone on until his death turning out Christmas Books adhering to the tried and true formula, and the public would have continued to snap them up in the tens of thousands, no matter what critics such as those anonymous snipers who wrote reviews for Macphail's, Chamber's Edinburgh Journal, Tait's Edinburgh Magazine, Parker's London Magazine, The Economist, The Northern Star, Fraser's Magazine, and, of course, The Times. However, the pressures of turning out his weekly two-penny journal, Household Words for readers of all classes and conditions combined with those of producing full-length novels in serial meant that he did not have the leisure for further productions of this sort for the Christmas book trade, a business he had done so much to create. Until 1867, Dickens and his talented stable of writers, notably William Wilkie Collins and Elizabeth Gaskell, worked together to produce something special for each Extra Christmas Number of the weekly journals Household Words and All the Year Round. Although these possess charm and narrative interest (the thriller No Thoroughfare especially has melodramatic power), many critics depreciate any and all of Dickens's attempts at the short story and its short-fiction twin, the novella:

Dickens's genius was not suited to short stories — the humour truncated becomes whimsy, the pathos removed from a wider social context becomes sentimentality, all those overtones of meaning which accrue to the great novels from the thematic patterns are lacking, the resulting stories seldom seem more than vapid magazine pieces, without, save in the last where Collins collaborated, even the suspense and lively action that mark the best Victorian magazine stories. (Wilson 181)

Related Materials on The Christmas Books

- "A very Moloch of a baby": Dickens's Funny Babies and Victorian Child Care Arrangements

- The Christmas Books of Charles Dickens — A Christmas Carol and Other Stories

- Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol (1843): An Intrduction

- The Naming of Names in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Dickens — "The man who invented Christmas"

- Vocabulary Notes for A Christmas Carol

- Recent editions of A Christmas Carol particularly useful for students and scholars

- Wilkie Collins's Mr. Wray's Cash-Box; or, the Mask and the Mystery (17 December 1851) — Imitating Dickens's Christmas Books (1843-48)

Images scanned by the author. [You may use them without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the author and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Butt, John. "Dickens's Christmas Books" (1951). Pope, Dickens and Others: Essays and Addresses. Edinburgh: UP, 1969. pp. 127-148.

Collins, Philip, ed. Dickens: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971.

_____. "Dickens on Ghosts: An Uncollected Piece [from the Examiner for Feb. 26, 1848]." Dickensian 59 (Jan., 1963): 5-14.

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life. A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That rang An Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth. A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edward Landseer. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1845.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. A Fancy for Christmas-Time. Illustrated by John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens, ed. Madeline House and Graham Storey (Vol. 1), Graham Storey and K. J. Fielding (Vol. 5). Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Volume One (1820-1839). Volume Five (1847-1849).

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. 2 vols.

Glancy, Ruth. "Dickens and Christmas: His Framed-Tale Themes." Nineteenth-Century Fiction 35, 1 (June, 1980): 53-72.

_____. "Dickens at Work on The Haunted Man." Dickens Studies Annual 15 (1986): 65-85.

Guida, Fred. A Christmas Carol and Its Adaptations: Dickens's Story on Screen and Television. London and Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co., 2000.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Kaplan, Fred. Dickens: A Biography. New York: William Morrow, 1988.

Slater, Michael, ed. Charles Dickens The Christmas Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. 2 vols.

Stone, Harry. "A Christmas Carol: Giving Nursery Tales A Higher Form." The Haunted Mind: The Supernatural in Victorian Literature. Ed. Elton E. Smith and Robert Haas. Lanham, Md., and London: Scarecrow, 1999. Pp. 11-18.

Tick, Stanley. "Dickens and The Haunted Man." Paper presented at the thirty-first annual meeting of the Dickens Society of America. De Paul University, Lincoln Park, Illinois, October 13-15, 2000.

Wilson, Angus. The World of Charles Dickens. London: Martin-Secker and Warburg, 1970.

Created 20 November 2004

Last modified 31 August 2025