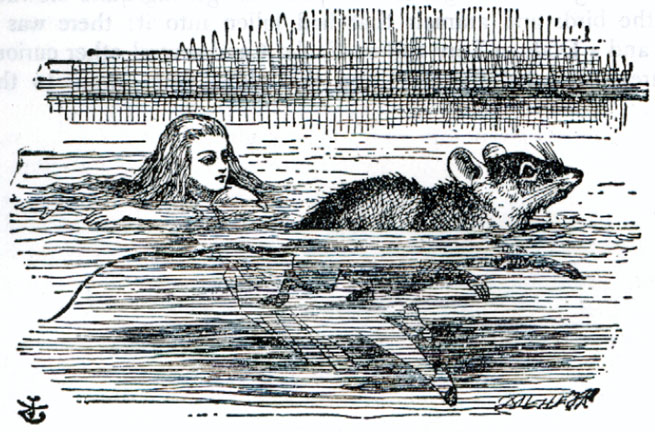

Alice in a sea of tears. (illustration to the second chapter of Alice in Wonderland) by John Tenniel. Wood-engraving by Thomas Dalziel.

Commentary by Leighton Carter

Though Carroll and Tenniel begin Alice in Wonderland with a bridge between reality and Wonderland — the White Rabbit — that allows the reader to enter somewhat gradually into the fantastical, they soon separate the two components of the anthropomorphic animal to violate fully the boundary between animal and man. By means of Alice's diminishments in size, she becomes similar to the Mouse she encounters swimming in the pool of tears. In the illustration for this scene, Tenniel emphasizes the characteristics that Alice and the Mouse share. Their positions in the water are strikingly similar — both stretch their hands (again the animal has human hands) out forward, kick their legs back and hold their heads above water — and, though they head in opposite directions, their bodies overlap in the visual frame. Carroll presses this similarity between Mouse and girl further towards inversion by giving the Mouse a fuller understanding of human decorum than Alice. Lost in her memory of Dinah, Alice offends the Mouse:

" . . . and she's such a capital thing for catching mice — oh, I beg your pardon!" cried Alice again, for this time the Mouse was bristling all over, and she felt certain it must really be offended. "We won't talk about her any more, if you'd rather not."

"We, indeed!" cried the Mouse, who was trembling down to the end of its tail. "As if I would talk on such a subject! Our family always hated cats: nasty, low, vulgar things! Don't let me hear the name again!" [Carroll 18-19]

Alice, unaccustomed to speaking with mice, underestimates the Mouse's sensitivity to discussing cats. The Mouse's denial of Alice's "we" and his invocation of family aligns him with the adults in Alice's reality who likely try to correct any of her childish faux pas. Alice's lack of realization about the danger of cats to the Mouse also shows her continuing belief in static identity. Harry Levin points out that "her shrinkages have taught her to look at matters from the other side, from the animals' vantage point," but only with a concern for maintaining proper decorum (184). Alice glosses over the more fearful aspect of her newfound smallness: not that she offends mice without meaning to, but that she could be eaten like the mice. Alice does not recognize that her beloved cat Dinah would likely not differentiate between her and a regular mouse; she still conceives of herself as the child that existed outside of Wonderland. Again, Wonderland's boundary-crossing changes jeopardize Alice's predefined sense of self without her fully knowing it.

The interaction between the Mouse and Alice proceeds to include linguistic reversals as well as behavioral. After the caucus-race in which a diverse group of animals participate, the Mouse agrees to tell his tale:

"Mine is a long and sad tale!" said the Mouse, turning to Alice and sighing.

"It is a long tail, certainly," said Alice, looking down with wonder at the Mouse's tail; "but why do you call it sad?" And she kept on puzzling about it while the mouse was speaking, so that her idea of the tale was something like this: — [Carroll 24]

Carroll then creates a visual embodiment of the pun by arranging the Mouse's tale typographically so that it forms the shape of a tail. He uses fantastic reversals — from word to object and from verbal punning to visual punning — to test the limits of language's applicability to the object-world. Alice discovers that Wonderland changes the nature of language and ordinary, verbal communication becomes as unreliable as Alice's growth cycles. [complete essay: ""Which way? Which way?": The Fantastical Inversions of Alice in Wonderland"]

Student assistants from the University Scholars Program, National University of Singapore, scanned this image and added text in 2000 under the supervision of George P. Landow. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the site and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Last modified 24 December 2007